Books of Sarah

In 2021, Jewish fiction grappled, in registers both tragic and comic, with questions of gender, power, and sexual politics.

Professor and literary critic Josh Lambert serves as a judge for two major prizes for American Jewish literature, meaning he reads as many new American novels by and about Jews as possible each year. In this annual column for Jewish Currents, he reflects on some of the previous year’s most compelling works of fiction that might be considered “Jewish” in one way or another, and what patterns emerged in this reading.

As is often the case, the new fiction I read over the past year seemed like a slow-motion echo of the news from half a decade ago: not ripped from the headlines, exactly, but carefully cut out, collaged in a scrapbook, meditated upon, and transformed. A number of novels and short story collections released in 2021 deal with gender and sexuality in ways that feel decidedly post-2016. Not coincidentally, this was a year in which scholars began dropping #MeToo into titles and subtitles, and a young philosopher’s exploration of “feminism in the 21st century” was a bestseller.

Related themes resonate throughout Jewish literature, which has had all sorts of distressing things to say about gender, guilt, and power, from the stories of the Bible to the masculinity-obsessed works of mid-century American Jewish novelists (and the contemporary prizewinning pastiches that draw on them). The best fictions I read this year enter into this tradition, speaking back to and rewriting it. They treat women’s abjection and resilience in both comic and tragic registers, taking as their subject the relationships among women who struggle under, reject, or transcend patriarchal limitations.

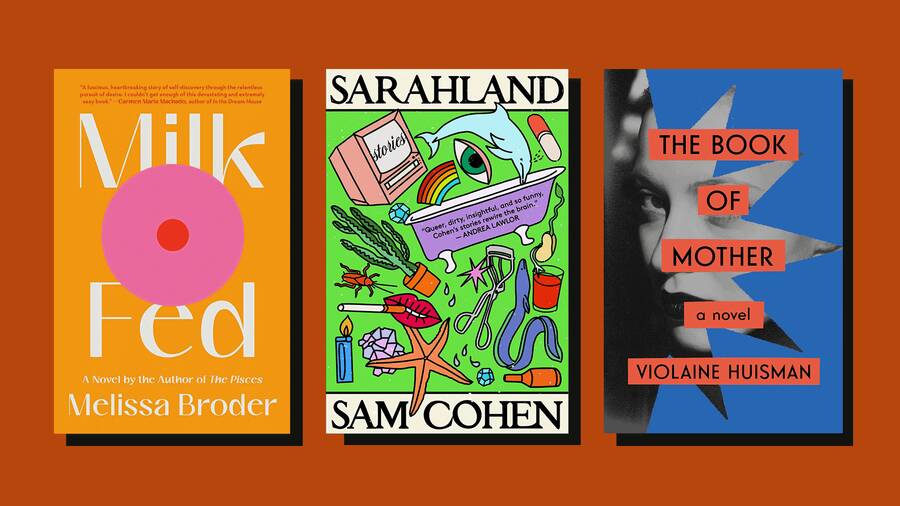

One obvious way in which gendered scripts are rewritten is through romances between women. In Melissa Broder’s Milk Fed, a few male characters skulk and preen, but at the novel’s heart is the love of two young women, Rachel and Miriam, and their appetites for food and for each other. Swinging wildly in tone, the novel treats eating disorders, toxic mother–daughter relationships, and the greasy glory of kosher Chinese food in prose that’s surprisingly loose, given the comic precision of the poems (and tweets) that established Broder’s reputation. It’s a literary novel, populated by golems that recall Xanthippe, in Cynthia Ozick’s The Puttermesser Papers, and the “woman made of cake” in Margaret Atwood’s Edible Woman. Intriguingly, though, the book’s principal intertext is that great American novel of Jewish toxic masculinity, Portnoy’s Complaint. Broder’s novel refashions Philip Roth’s, exuberantly, from a female perspective: If all the explicit sex and corny jokes don’t make her source obvious enough, Broder drops a few unmistakable hints, naming a character “Spielvogel,” like Portnoy’s shrink, and having Rachel note that when she’s kissing Miriam, she sucks her tongue “like a piece of liver.” (Broder’s website also currently features a collage with Roth’s face Photoshopped onto a votive candle.) This left me pondering a question that already feels like a contemporary cliché: Is gender-swapping a misogynist classic a meaningful feminist intervention? (Discuss among yourselves.)

A somewhat deeper, stranger attempt at rewriting old stories against their grain arrives in Sam Cohen’s debut story collection, Sarahland. The book’s organizing gimmick is, simply and brilliantly, the name Sarah. One narrator, who attends a midwestern college in the age of Napster, lives in an “off-campus dormitory where 90 percent of the girls were named Sarah” and everyone’s Jewish. The narrating Sarah had hoped “college would be exactly like summer camp,” a girls-only space that was “the only time/place that counted as Real Life” for her. Instead, she comes to realize—thanks, in part, to new friends who quote bell hooks—that her aspiration is “to change the world, to make it void of money and boys at least.”

In the rest of the stories, Cohen widens her focus onto all the “Sarahs, maybe-Sarahs, and Sarahs of the past and future” (as her dedication phrases it). In “Gemtstones,” two fluidly-gendered poets play an arcade game stocked with Sarah avatars: Silverman, Michelle Gellar, Jessica Parker, Schulman. To her credit, Cohen perceives that a world filled with Sarahs who love one another also becomes a pretext for trite, self-serving gestures of all kinds, including male self-abnegation: In a moment that rings familiar, MFA students in one story discuss a friend, Matt, who’s “been considering stopping writing. He says the world doesn’t need any more white gay poets.” “That’s so cool,” another writer jokes. “Like . . . is he also going to kill himself?” But still, the collection’s Sarahs hold out hope for new narrative and social possibilities. In “The First Sarah,” a midrash on Genesis, a would-be patriarch, Abey, plays second fiddle to his concubine Hagar. She and Sarah pray not to Abey’s narcissistic male God but to Mother Nature, who blesses them joyfully: “Lesbians should be the mothers of the future humans of this earth.”

Other standout works this year dive into the darkness that hovers around the edges of Broder’s and Cohen’s playful, upbeat stories. Violaine Huisman’s first novel, The Book of Mother—published in French as Fugitive parce que reine in 2018, and now translated into English by Leslie Camhi—chronicles, in hilarious and sharp prose, the cathexes between a traumatized and traumatizing mom and her two daughters. A work of autofiction by a Parisian who has lived in New York for the second half of her life, it’s an extraordinarily powerful book that documents how the contingencies of 20th-century Europe led to the narrator inheriting “a poisonous history, whose truths and falsehoods were difficult to untangle.” Those poisons reach the narrator, Violaine, in the form of her mother Catherine’s obscene tirades, erratic parenting, and frightening emotional intensities—but also in the person of one tremendously creepy and likely abusive Jewish grandfather.

After the girls, as children, had been told that their grandfather “had died in the Holocaust,” he “appear[ed] one day on [their] doorstep,” very much alive. “To describe him as lecherous,” Violaine remarks, “doesn’t do justice to the perversity of his character: everything about him seemed threatening and seedy,” and since he “entered our household just as we were taking our first tentative steps in the realm of sexuality,” this “monster” destroyed “whatever possibility of joy or exploration might have existed for us.” In a childhood peopled extensively by the distressing repertory company of Catherine’s lovers and suitors, Violaine remarks, “No masculine incursion into our lives ever distressed us more than this one.”

Jewishness trickles down to Violaine from this disgusting man, as well as from her somewhat absent intellectual father, but it is her mother who shows her how to value that inheritance. In the section of the novel that imagines the internal thoughts and private experiences of Catherine, we learn that one of her lovers, a woman named Claude, “encourages her to read, women especially, but also great Jewish writers, sensing in Catherine’s disordered stories how important her father’s religion is to her.” Specifically, Catherine reads Nathalie Sarraute, Simone Weil, Stefan Zweig, and Albert Cohen’s Belle du Seigneur—classic texts by and about Jews struggling with their position in European culture, as she was herself. Despite all she’s suffered, and all the suffering she imposes on her daughters, Catherine “lay[s] claim to her Jewishness . . . in order not to find herself alone, to assert that she belonged to a people, a tribe; she rewove her past on the loom of History to give it meaning, give it weight.” For one very troubled, unstable woman—and, the novel suggests, possibly for her daughters—literary Jewishness represents the possibility of meaning, stability, even comfort.

Remarkably, and strangely, Jewishness plays a similar role in Hanna Halperin’s Something Wild, a novel that otherwise has very little in common with Huisman’s. First, I should note that it’s an unusually distressing novel to read; Halperin has worked as a domestic violence counselor, and if I tell you that the novel seems to have drawn, chillingly, on what she observed in that role, I hope that will serve to alert any readers who would prefer to stay away.

The central question of Something Wild is whether two women in their late 20s and early 30s, the sisters Nessa and Tanya Bloom, can do anything to rescue their mother, Lorraine, from their abusive stepfather, Jesse. But as memorably distressing as Lorraine’s story is, what makes Halperin’s novel even more effective is its focus on Nessa and Tanya, and the way pernicious, archaic ideas about sex and gender, including their mother’s, have played out in many aspects of their lives.

As in Huisman’s novel, here Jewishness plays a role in the strained relations between the sisters and their parents. While Lorraine is a lapsed Catholic, the sisters’ father, Jonathan, is Jewish, and among the many unfortunate consequences of Jonathan’s having left when they were preteens is that it severed the girls’ connection to Judaism: Nessa’s bat mitzvah gets canceled, Tanya stops going to Hebrew school. “Without Jonathan around,” Halperin writes, “they all gave up on being Jewish.” Because they’ve lost that link, and because Jonathan is handsome and successful, and because his second wife is a gorgeous, sophisticated Jewish woman, the sisters vaguely understand Judaism as the opposite of their mother’s financial and romantic struggles. Tanya “associates Judaism with family, with togetherness, with childhood . . . . To her, the memory of Judaism is a tender one, like waking up on a snow day as a kid.”

Accordingly, Tanya—who in the novel’s present is 28, and a hotshot young lawyer—has found a nice Jewish boy to marry: Eitan, “gentle and solemn,” “his Semitic features handsome and familiar,” a Mount Sinai-trained doctor who grew up Orthodox but was too much of a feminist for the “hypocrisies” that made his mother and sisters sit “in the balcony, where it was hot and crowded,” yet nonetheless wants “Jewish babies.” If part of what Halperin wants us to recognize is the distressing extent to which our culture tells young women that their financial and physical safety depends upon their ability to satisfy men’s desires, this Jewish man signifies Tanya’s strength and clarity of purpose—she has firmly grabbed the brass ring that her mom fumbled.

Without spoiling the plot, or gainsaying some of its brutal turns, I can say that Halperin seems intent on giving Tanya and Nessa a happy ending, or at least a hopeful one. But in reminding us that behind so much normative gender and sexual identity—in their Jewish guises as much as any others—lies barely restrained violence, the novel stops short even of the comfort of bitter laughter one gets from books like Broder’s, Cohen’s, and especially Huisman’s. In our time and place, though—where physical and sexual abuse remain rampant despite being under the media spotlight, in Jewish communities as well as everywhere else—how much comfort do we really deserve?

Josh Lambert is the Sophia Moses Robison Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and English, and Director of the Jewish Studies Program, at Wellesley College.