An orange grove in Indian River, Florida, 1898.

Ghosts of the Groves

In Israel and Florida, violent parallel histories of citrus cultivation have set the stage for a budding agricultural alliance.

On Christmas Eve, I walked into the Citrus Tower in Clermont, Florida, a former epicenter of the state’s orange production. Located in the northern part of the Lake Wales Ridge—a series of hills that stretches 100 miles across Central Florida—the 226-foot tower was unveiled in 1956 to celebrate what was then one of the state’s leading industries. Back then, the Ridge had one of the highest concentrations of orange trees in the world, and the tower annually drew an average of 500,000 tourists, who would gaze from its heights upon endless rows of thorny evergreens laden with white blossoms and glowing fruit. In the decades since—including in the 1990s, when I was growing up in Central Florida—oranges have been synonymous with the state, adorning license plates and tourism posters. Even now, the orange blossom is the state flower, and the orange is the state fruit.

The Citrus Tower, built in 1956 as an observation tower above Central Florida’s citrus groves, in Clermont, Florida.

Today, the abundant groves that once surrounded the tower are gone, victims of citrus greening disease, an insect-borne bacterium that was first detected in Florida in 2005 and has since wiped out three quarters of the state’s orange trees. But inside the tower, rows of evergreens still reach skyward on black-and-white reels that play on a loop. After pausing in the lobby to admire the bygone groves, I paid $11 to ride an elevator to the top of the building, where I stood on a glass-enclosed observation deck and surveyed the housing subdivisions that have cropped up all around, their names recalling the state’s colonial history and the citrus orchards that grew from seeds brought by the first conquistadors: The Colony, Plantation Acres, Hacienda Estates. There wasn’t an orange tree in sight.

On my way out, I stopped at the lobby gift shop to buy a bottle of Uncle Matt’s Orange Juice. Billing itself as the largest purveyor of organic juice in the country, Uncle Matt’s is a Clermont-based company that traffics in its down-home image. But while the company maintains a corporate headquarters a five-minute drive from the Citrus Tower, it began sourcing some of its oranges from Mexico in 2015. In fact, nearly all of Florida’s formerly locally sourced labels now rely on imports. This trend accelerated in 2017 after Hurricane Irma devastated every citrus-producing county in Florida. That year, the Sunshine State eked out 53.7 million boxes of oranges and imported 63.95 million, of which 46% came from Brazil and 44% from Mexico. Last season, Florida growers produced 16 million boxes, the fewest since the Great Depression. This has opened the door for what’s left of the Florida orange industry to become the province of multinational corporations. Unable to withstand the dual afflictions of rampant citrus greening and increasingly intense hurricanes, most of the state’s growers have sold to large juice brands like Tropicana and Minute Maid (owned by a French private-equity behemoth and Coca-Cola, respectively), while companies like Cutrale, the American subsidiary of Brazilian citrus giant Sucocitrico Cutrale, have bought up processing plants and storage facilities.

Israeli companies, in particular, have carved out a high-tech niche in the globalized Florida citrus industry. One notable example is the Haifa-based flavor and ingredients giant Frutarom, known for developing new methods of distilling citrus oils into flavor packets. Just a few years after Frutarom started buying up citrus oil extraction enterprises on the Ridge in 2014, it was purchased by the New York–based International Flavors and Fragrances, becoming the second-largest company traded on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. Other Israeli agricultural technology, or ag tech, companies have generated excitement in Florida by claiming that they may have discovered a cure for citrus greening. During a 2019 trip to Israel, then–Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Nikki Fried told The Tallahassee Democrat that she believed these innovations could be the key to saving the state’s trademark industry. “We would be fools not to be here and bring that technology back to the United States,” she said. These declarations built on a years-long collaboration between the Israeli and Floridian tech sectors. Florida has become the US’s “epicenter for Israeli-based start-ups,” according to one Nasdaq article, providing a home base for dozens of companies in sectors from cybersecurity to medical technology. Florida’s citrus industry may be struggling, but ag tech—some of it citrus-focused—looks like a growth area thanks to, per Nasdaq, “the cross-pollination of ideas and practices between Israeli entrepreneurs and Floridian businesses.”

This budding partnership is a natural extension of the parallel histories of Israeli and Florida citrus. In both places, generations of settler colonists have valued oranges not only as a source of wealth, but also as a treasured part of their mythology. Early Zionist settlers in Palestine saw their agricultural output in morally and socially redemptive terms; their famous promise to “make the desert bloom” positioned cultivation as a route toward seizing the land, and oranges, in particular, became a narrative device to scaffold claims of rightful occupancy. In Florida, where oranges were likely introduced by Spanish colonizers in the 16th century, they came to represent the idea that the terrain was a potential paradise that only Europeans could bring to fruition.

As far-right political projects have consolidated power in both Israel and Florida—with Governor Ron DeSantis’s administration openly working to push leftists, immigrants, LGBTQ people, and other minority groups out of Florida’s social body, and Israel currently perpetrating a genocide in Gaza, seeking to complete the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians that it embarked on more than a century ago—shared politics have become the basis for an agricultural alliance. This fact was on display at the Citrus Tower, which was purchased last September by Ralph Messer, a notorious Christian Zionist (best known for appearing in a viral YouTube video in which he wrapped scandal-ridden Georgia megachurch bishop Eddie Long in a Torah scroll). Finishing my juice in the lobby, I scrolled through the site’s Instagram and quickly came upon a “Stand with Israel” post from October, laid over a photograph of the tower lit up in blue and white. I then made my way over to the gift shop, where I was met with a screen broadcasting The Hope—a docudrama produced by the Christian Broadcasting Network that celebrates the founding of the State of Israel—above shelves of orange-themed kitsch. Everywhere I turned, I saw romantic depictions of a time when citrus was king in Florida punctuated with Zionist iconography.

But the brand of nostalgia for sale at the tower seems less and less to the public’s taste. On the day I visited, I saw only four tourists; the site now attracts fewer than 18,000 people annually. Instead, the tower’s genre of gauzy mythmaking seems to be giving way to the more overt symbolic register of Israel and Florida’s joint techno-optimist fantasies, encapsulated by the various “precision agriculture” experiments and citrus research and development projects underway only miles from where I stood that day. These old and new lexicons share an underlying grammar, which strengthens the capacity of settlers to lay claim to a place and, in the process, remake the very land beneath their feet. At the same time, the shift signals that the orange is once again being pressed into service, summoned to lend its glow and sweetness to projects of violence and supremacy.

The orange is once again being pressed into service, summoned to lend its glow and sweetness to projects of violence and supremacy.

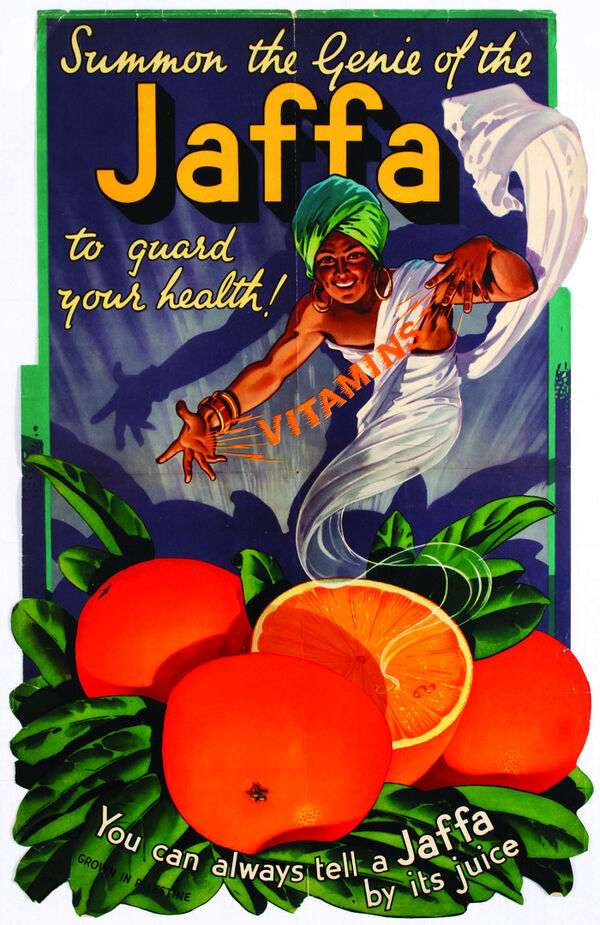

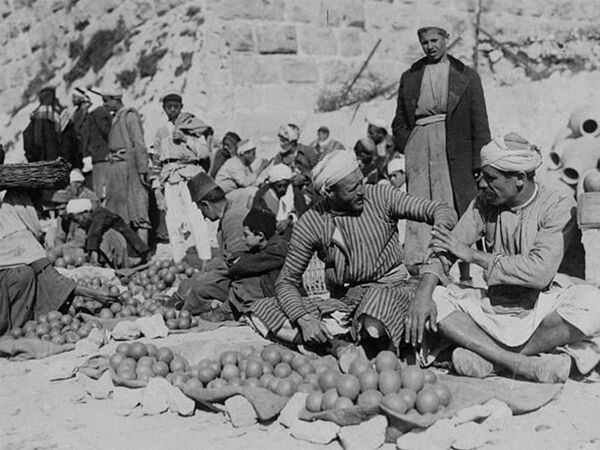

Oranges have grown in historic Palestine since at least the 10th century, clustered in small orchards in the countryside, or peeking out of walled gardens from Jaffa to Jerusalem. The fruit became an important export beginning in the mid-19th century, after the Ottoman Empire instituted land reform laws that dispossessed many Palestinian farmers, pushing them into urban areas. Some found work picking citrus in the port city of Jaffa, where ideal growing conditions and new grafting techniques had produced a new varietal soon to be known worldwide: The Jaffa orange, also known as the Shamouti orange, which has a sweet, pleasing flavor and a thick skin that makes it especially well-suited for export.

Propelled by its new labor force, Jaffa’s citrus industry boomed. Between 1850 and 1880, the land devoted to orange groves quadrupled, and Palestinian merchants began shipping the fruit across the Ottoman Empire and Europe, where it became a sought-after symbol of luxury. By the end of the century, citrus was Palestine’s largest export, cherished as an emblem of modernization and cultural pride. As the historian Mustafa Khaba recounts, when the Palestinian newspaper Filastin conducted a survey during the British Mandate asking respondents about what flag they would like to see represent Palestine after independence, the majority chose the green and orange of citrus.

As oranges were becoming increasingly important for Palestinians, they were also taking on symbolic significance for early Zionist settlers, who understood the planting of trees as a metaphor for reestablishing roots and claiming sovereignty after centuries of exile. In Theodor Herzl’s 1902 novel, Altneuland, which imagines a utopian future for Jewish settlement in Palestine, he tells of a Prussian aristocrat and Viennese intellectual who pass through Palestine after spending 20 years on a remote island. When two decades earlier the pair had stopped in Jaffa, they encountered a sparsely populated and primitive society; they are now astonished to find a harmonious, advanced “New Society,” as European Jews have reclaimed their destiny by immigrating to their titular Old New Land. The novel’s sole Arab character, Reschid Bey, notes that while citrus groves pre-dated the arrival of Jewish immigrants, harvests and profits increased after the newcomers applied their agricultural knowledge. Zionist settlers alone, Herzl makes clear, possess the technical expertise and tireless work ethic to bring the land’s potential to fruition.

Oranges took on symbolic significance for early Zionist settlers, who understood the planting of trees as a metaphor for reestablishing roots and claiming sovereignty after centuries of exile.

Jaffa orange crate label, circa 1940s.

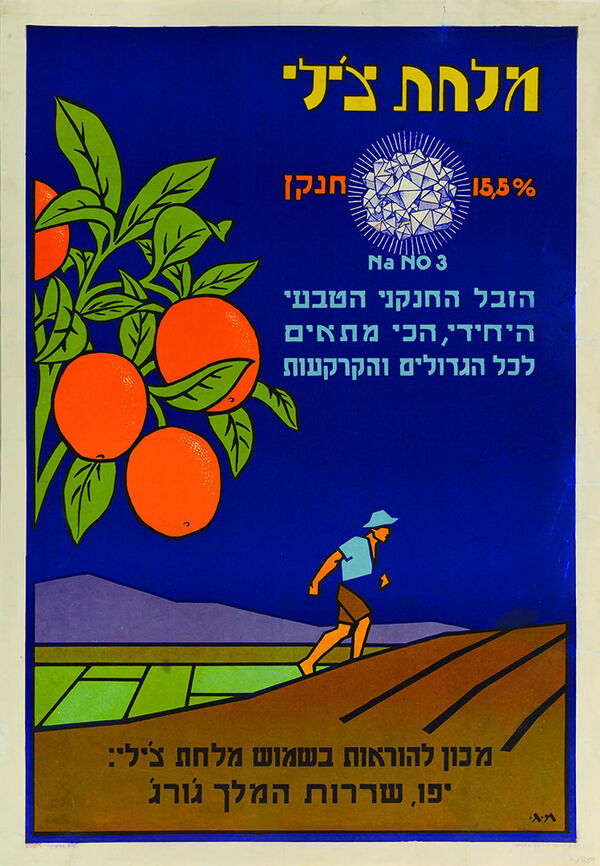

A fertilizer ad by Meir Gur-Arieh featuring Zionist pioneer iconography, circa 1920.

Indeed, even before the founding of the State of Israel, citrus groves were a site where early Zionists struggled over fundamental questions of land and labor. When Jewish immigrants began cultivating citrus at the beginning of the 20th century, they regularly employed Palestinian workers, relying on their hard-earned expertise. This created tension with the Histadrut, or General Organization of Workers in Israel—one of the most powerful institutions in the Yishuv, the parastate organization for Jewish settlers in Palestine—which, in 1929, launched a campaign demanding that Jewish-owned groves employ only Jews. The Histadrut was driven by a sense of practical urgency: Tasked by the Yishuv with finding jobs for newly arriving Jewish immigrants, it was struggling to keep up with demand. It was also motivated by ideology. The early Zionist movement emphasized “Hebrew labor” (avodah Ivrit)—the dream of an exclusively Jewish workforce as a means of laying the ground for a Jewish state—and the related notion of “the conquest of labor” (kibbush ha’avodah), the idea that manual labor would redeem a Jewish people physically and spiritually diminished by life in diaspora. By working in the fields and groves, in other words, early Zionists sought to advance their project of settlement, and to revitalize themselves in the process. Ultimately, the policy failed, with Palestinians protesting what they identified as a prelude to accelerating land theft and expulsion and Jewish grove owners defending their right to hire experienced indigenous workers. This contributed to an ambivalent process of race-making, in which Jewish immigrants sought to replace the native “Other” even as they relied on their labor.

The citrus industry in particular, and agricultural production more broadly, were critical to the creation of a Palestinian underclass and the fortification of the myth of Jewish supremacy. Echoing their characterization of the Palestinian people as primitive, Jewish settlers derided Palestinians’ densely planted groves as unkempt; Jewish settlers, by contrast, laid out their orchards according to a technique developed in California, with neat rows separated by wide spaces to allow room for new mechanical irrigation equipment. As Jewish settlers sought to project their scientific prowess to the world, Mandate Palestine became a testing ground for new technologies—including, for example, hydrogen-based pesticides and synthetic fertilizers promoted by the British chemical company Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), a wide-reaching imperial corporation with offices in Egypt and India, which opened a branch in Palestine in 1928. Run by Yechiel Weizmann—the younger brother of Chaim Weizmann, a Russian biochemist who would become the first president of Israel—ICI Levant honed the ability to eliminate insects that threatened citrus cultivation. The Yishuv could soon boast of its own chemical innovations with the founding of Frutarom Palestine Ltd.—which cultivated aromatic plants in order to distill their flavors for fine ingredients and essential oils—established in 1933 with a personal investment from Chaim Weizmann. The elder Weizmann even reportedly convinced Lord Halifax, the British Foreign Secretary, to use Frutarom to supply British troops with vitamin C concentrate packets during World War II. Such contracts bolstered the Zionist project’s profile on the international stage, and also garnered material benefits, encouraging Britain to patronize the Yishuv.

When, in the wake of World War II, Zionist forces carried out massive land theft to found the State of Israel, expelling more than 750,000 Palestinians in the process, they were particularly eager to seize Palestinian orange groves, decimating the Palestinian economy and consolidating Jewish wealth in one fell swoop. As the historian Ilan Pappé writes in The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, leading figures in the Yishuv established an unofficial Transfer Committee to oversee the expulsion of Palestinians, appointing as one of its three members the Jewish community’s leading citrus grower, Ezra Danin, formerly a high-ranking intelligence operative in the largest Zionist militia, the Haganah. According to historian Hillel Cohen, Danin systematically recorded information on every grove in Palestinian hands, which Zionist forces used to seize them for the new Jewish state. By January 1949, the Yishuv had seized 70% of Palestinian groves (a proportion that would increase in the following decade). In May of that year, a group of Arab states wrote to the United Nations calling in vain for the groves to be repatriated. “The orange groves constitute the principal wealth of the Arabs in the territory at present occupied by the Israelis,” they noted. “According to representatives of the refugees, the value of these groves is approximately £150 million sterling,” equivalent to $7.9 billion today.

This massive dispossession charged oranges with contradictory symbolic resonance. For Palestinians, oranges came to represent an unshakeable connection to their homeland, and their grief at all that had been taken from them. In a short story included in his classic 1962 collection, Men in the Sun, Palestinian writer and revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani described how the Nakba had created a “land of sad oranges.” In the story by that name, a boy travels from Jaffa to Acre during the Nakba, watching as women weep while buying oranges and witnessing his own father “burst into tears like a despairing child” when he gazes upon the fruit: “And all the orange trees that your father had abandoned to the Jews shone in his eyes, all the well-tended orange trees that he had bought one by one were printed on his face and reflected in the tears that he could not control in front of the officer at the police post.”

In a short story, Palestinian writer and revolutionary Ghassan Kanafani described how the Nakba had created a “land of sad oranges.”

Palestinian orange sellers in Jaffa, 1920.

Meanwhile, for the new Israeli state, the orange signified a future ripe for the taking. The Ministry of Tourism prominently featured anthropomorphic oranges carrying Israeli flags in films and posters designed to encourage European Jews to immigrate; youthful and merry, the fruit stood in for a new generation of “native” Israelis, free of the burdens of their diasporic forebears. Eager to bolster its international reputation, the state recruited celebrities like Ingrid Bergman, Louis Armstrong, and Julie Andrews to be photographed with crates of oranges, and registered Jaffa Orange as an Israeli trademark. Roni Nakar, an official in the Ministry of Agriculture, reflected, in a 2009 documentary, on the state’s early years: “There are two brands that were marketed successfully abroad. One is the Uzi machine gun . . . The other is [the] Jaffa [orange].”

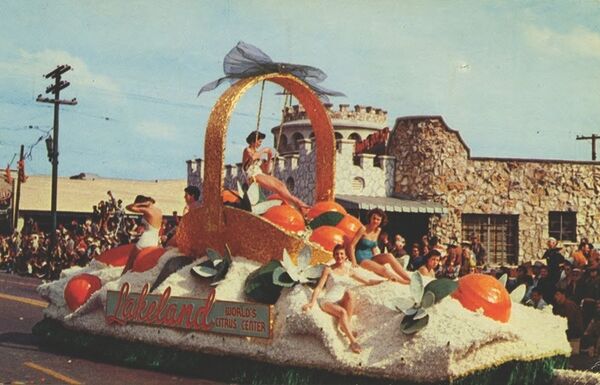

Oranges almost certainly came to Florida with the Spanish colonial expedition led by Juan Ponce de León in the 16th century—an origin story that Florida growers have proudly mythologized ever since. As journalist John McPhee writes in his book Oranges, “The Florida Citrus Commission likes to promote him as a man who was trying to find the Fountain of Youth but actually brought it with him,” in the form of a magical fruit that could combat scurvy, which ravaged Spanish settlers on long maritime trips. In 1763, Spain relinquished control of Florida to the British in exchange for territories seized during the Seven Years War. The British—intent on bringing raw materials to the metropole, where they used them to manufacture products to sell globally—offered white settlers land grants to expand the plantation system throughout Florida’s northeastern coast. Some of these new plantations grew citrus, which became a commercial crop for the first time in the Americas; enslaved people cultivated the fruit that was then shipped to other parts of the continent and across the Atlantic. The industry remained economically important as the territory returned to Spanish control in 1783, and only grew in the period following 1821, when Florida became a possession of the United States. (It was admitted to the Union in 1845.) In 1834, two and a half million oranges were shipped from St. Augustine to the northern states. The next year, a devastating freeze destroyed the majority of citrus plantations from Charleston to Jacksonville, prompting growers to push deeper into Florida, rebuilding their groves farther south.

After the abolition of slavery in 1865, Florida sought to recast its image in the hopes of securing a place of pride in the shifting global economy. White Republican boosters dreamed of extricating the new state from the parochial associations that plagued members of the former Confederacy and transforming Florida into a center for tourism and a commercial gateway to the world. (The “American Italy,” the Fort Myers Press called it.) More than any other southern state, Florida shifted its economy away from cotton and tobacco—which readily summoned the specter of slavery—and pursued new industries, resorts, and groves. Workers flocked to the state, including thousands of poor white people, who were encouraged by the 1862 Homestead Act, which promised that any US citizen could take possession of land he inhabited for five years. These new arrivals picked and packaged citrus alongside migrants from Cuba and the Bahamas, as well as recently emancipated Black Americans, who toiled for lower wages with minimal rights.

Even as the citrus industry’s exploitative practices perpetuated a Black underclass in Florida, white paeans to the state framed its peerless oranges as a cure for America’s racial ills. As former cotton and indigo plantations were converted into citrus groves, noted northern abolitionists chose to make their homes in Florida following the end of the Civil War, lured by the fantasy of leaving the albatross of slavery behind. Among them was Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who purchased a St. John’s River plantation at the dawn of Reconstruction, with the intention of growing oranges. In the years that followed, she wrote memoirs and articles extolling the curative quality of the Florida landscape and the transformative properties of the cherished fruit—which she believed was capable not only of healing illnesses caused by the northern cold, but also of occasioning a radical shift in the racial dynamics of the economy. Stowe imagined the orange groves as a metamorphic site where the formerly enslaved, now laboring alongside white workers, might be reborn as free men and women.

White citrus growers did not hesitate to unleash vigilante violence on striking workers, often summoning the Ku Klux Klan to target the homes and farms of Black families.

Grove worker near Tampa, Florida, 1954.

Into the 20th century, the idealized image of the citrus industry continued to depend on a Black workforce, as well as on white terror that made it potentially fatal for laborers to challenge brutal and extractive conditions. At the end of World War I, Black workers—their expectations bolstered by the economic and social mobility that many experienced in the army—organized strikes throughout Florida to demand higher wages. White citrus growers did not hesitate to unleash vigilante violence, often summoning the Ku Klux Klan to target the homes and farms of Black families. (The state, which was the site of 311 lynchings between 1877 and 1950, among the highest numbers per capita in the country, was a Klan stronghold.) The industry’s constitutive anti-Blackness persisted in the decades that followed. As young men entered the military en masse during World War II, growers scrambled to find labor. In January 1945, Florida Governor Millard Caldwell sent letters to the state’s sheriffs, urging them to enforce “work or fight” laws, which authorized police to enter the homes of workers accused of “loitering, loafing, and absenteeism.” These laws targeted Black workers, who were arrested and fined—then taken from jail in chain gangs to work off their fines in white-owned citrus groves. On the job, their hands were cut by the thorns protecting the oranges—the bright treasures shipped around the world in boxes reading Florida Citrus. The demand for the fruit, and for the labor that produced it, only increased after World War II, when the newly minted Minute Maid (formerly the Florida Fruit Corporation) repurposed the method of concentrating orange juice that it had invented for US soldiers suffering from scurvy in order to sell frozen concentrate to a wide public.

As the exploited workforce grew and escalated their organizing efforts, grove proprietors tightened their bonds with both legal and extralegal anti-Black forces. In Lake County, the seat of the citrus empire at the time, growers were instrumental in the election of Willis McCall, a segregationist and former USDA produce inspector, as county sheriff. During his seven-term tenure from 1944 to 1972, McCall further entrenched the racist labor structure, regularly dragging Black workers from their homes in accordance with “work or fight” laws. In 1946, he chased a union organizer out of Lake County in his Oldsmobile—then blamed Communists for stirring up trouble among Black workers. In 1949, in the small city of Groveland, four Black men—Ernest Thomas, Samuel Shepherd, Walter Irvin, and Charles Greenlee, who had come to the town to work in the orange groves—were falsely acccused of raping a 17-year-old white woman named Norma Padgett. Within hours, mobs of white residents from across Central Florida gathered in Lake County, burning and looting the homes and businesses of Black residents. That week, a mob of hundreds of white men, including poor grove workers, killed Ernest Thomas. When the Supreme Court ordered a retrial in 1951, McCall shot Irvin and Shepherd, who were in his custody. (Shepherd was killed; Irvin survived by playing dead.) The alliance between citrus barons and other agents of white supremacy was not confined to law enforcement; it also shaped the law itself. Citrus shipping mogul C.V. Griffin famously funded the successful gubernatorial bid of Florida Dixiecrat and former Klan member Fuller Warren in 1948, and in exchange, Warren tapped Griffin to write the state’s

citrus code.

It was under this code that the newly formed Florida Citrus Commission was empowered to hire former beauty queen Anita Bryant as its spokesperson in 1969—a figure so popular that she had sung at both the Democratic and Republican political conventions the year prior. A decade before her notorious anti-gay crusade, Bryant appared frequently in citrus ads, posing before an orange tree or ushering her twin toddlers into the kitchen to pour them cups of juice. Bryant, who punctuated each commercial with a variation on her catchphrase, “A day without orange juice is like a day without sunshine,” secured Florida oranges’ association with the idyllic white, heteronormative Christian family. Even after the Citrus Commission canceled her contract in the 1980s, in response to national protests of her increasingly overt bigotry, Bryant would persist in the public imagination as the figure most visibly associated with the fruit.

Anita Bryant, who punctuated each commercial with her catchphrase “A day without orange juice is like a day without sunshine,” secured Florida oranges’ association with the idyllic white, heteronormative Christian family.

A “Lakeland: World’s Citrus Center” float at the Gasparilla Parade in Tampa, Florida.

The decade that Bryant was let go, a series of devastating freezes in Central Florida pushed the industry even further south. Citrus growers sold thousands of acres of land to housing developers and cattle farmers, and thousands of grove workers were left without employment. In South Florida, newly arrived undocumented immigrants from Mexico and Guatemala comprised a reservoir of cheap labor. The industry continued to thrive on the backs of this exploited workforce until 2005, when citrus greening disease was first detected in Florida. The bacteria spread quickly, devastating groves throughout the state in the early 2000s and vastly restricting the opportunities for seasonal workers. In 2018, Hurricane Irma further decimated the industry, compounding the scarcity workers faced. Thousands of citrus trees were turned upside-down, leaving their mangled roots exposed to the air. Millions of orbs of once-golden fruit, now green and bitter, lay split open on the ground.

In May 2019, shortly after he became governor of Florida, Ron DeSantis traveled to Israel and the West Bank, accompanied by more than 100 of his state’s legislators, lobbyists, and businesspeople. He sat down one-on-one with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (after which he boasted that Florida is “the most pro-Israel state”); became the first Florida governor to visit a West Bank settlement (where he received an honorary degree from Ariel University, the only accredited Israeli university located in the settlements); and held a state cabinet meeting at the US embassy in Jerusalem—a violation of Florida’s Sunshine Law, which specifies that state meetings must be accessible to the public—during which he signed a bill adopting the controversial IHRA definition of antisemitism, making criticism of Israel punishable in Florida’s public schools and universities. His office celebrated the trip as a “historic business development mission,” touting the potential to forge new commercial ties between Israel and Florida. In a darkened auditorium near Ben Gurion Airport, DeSantis delivered the keynote address at the Israel–America Business Summit, and he and his entourage spent days at the conference meeting with Israeli companies in fields from cybersecurity to green technology.

While in Israel, DeSantis sought to solidify partnerships that promised to bolster his state’s prized citrus industry. At the Volcani Institute, the leading Israeli agricultural research center, Commissioner of Agriculture Fried, who had joined DeSantis on the trip, watched as researchers proudly demonstrated drone technology designed to identify early signs of citrus greening disease. (Volcani also trotted out drones that could monitor citrus trees’ water and nutrient levels.) Fried lauded the Israeli innovations in interviews, suggesting that Israel might hold the key to the challenges facing Florida citrus, while Florida could offer Israeli start-ups an unparalleled laboratory for their experiments. “They may be able to detect [citrus greening] within six months of it seeping into the ground,” she explained, but they “don’t have [sick] trees” on which to test their discoveries.

Ultimately, Fried’s ambitions were stymied when the havoc wreaked by citrus greening was compounded by a new crisis: the Covid-19 pandemic, which began less than a year after she returned from Israel and became a deadly disaster for Florida farmworkers, who were excluded from DeSantis’s vaccine rollout. But Israeli companies have nevertheless begun seizing the opportunities created by the state’s rampant citrus greening. The Tel Aviv-based startup SeeTree AI, for example—which advertises what it has called “an intelligence network for trees,” promising to use “drones, light aircraft [and] satellites” along with “unique data and AI” to monitor tree health and optimize productivity—has two active contracts with Florida customers, and features them prominently in its marketing materials. Such collaborations seem poised to deepen now that citrus greening, as of 2022, has also been detected in Israel.

Florida has also become both a testing ground and a calling card for Israeli companies claiming to have solutions to other ecological problems. For Netafim, the largest digital irrigation corporation in the world, Florida was the gateway to the American market. In Israel/Palestine, the company sells systems that are used to funnel more than 80% of the West Bank’s biggest aquifer to Israel and its illegal settlements; in Florida, such digital irrigation techniques appeal to those grappling with overwatering, which can create toxic runoff from fields treated with fertilizers and pesticides, causing, most notably, an explosion of deadly blue-green algae in lakes and rivers. In 2019, DeSantis signed a contract with the Israeli company BlueGreen Water Technologies, which professed to have a product that could kill the foul-smelling ooze, also known as cyanobacteria. The following year, BlueGreen Water Technologies dumped roughly 2,000 pounds of algaecide into Lake Minneola, a five-minute drive from the Citrus Tower, and in 2021, it poured another five tons into the Caloosahatchee River in southwest Florida. Two weeks later, the Fort Myers News-Press reported that the Caloosahatchee’s water was “still not safe” for swimming, and noted that the pesticide posed dangers to “birds[,] bees and other beneficial insects.” Today, several years on, the waters treated by BlueGreen are still beset by algae; Florida environmental journalist Craig Pittman has compared using the company’s chemicals on cyanobacteria to “taking aspirin for a brain tumor.” In other words, the famed innovations of Israeli ag tech have yet to deliver on their promises in the Sunshine State.

The famed innovations of Israeli ag tech have yet to deliver on their promises in the Sunshine State.

A geneticist at the University of Florida Citrus Research and Education Center holds an orange affected by citrus greening disease at a grove in Fort Meade, Florida, 2018.

But for Israel, the purpose of these exports seems to be as much about tilling symbolic soil as altering farmers’ material fortunes. At the 2018 AIPAC conference, Netanyahu cited “precision agriculture” as a key example of how Israel “revolutionizes old industries and . . . creates entirely new industries.” He described visiting his “great friend” Prime Minister Narendra Modi in India, admiring cherry tomatoes grown with Israeli technology—an example, he said, of how his nation was transforming the world by selling its agricultural tools “everywhere.” Such commercial partnerships, he boasted, lay the groundwork for diplomatic relationships, securing a global order that guarantees Israel’s prosperity: “Pretty soon, the countries that don’t have relations with us, they’re going to be isolated. There are those who talk about boycotting Israel? We’ll boycott them.”

Around the time Netanyahu captivated AIPAC attendees with descriptions of Israel’s technical prowess, he began incorporating the Volcani Institute into the tour he gives to visiting heads of state, stitching it into the official narrative that Israel presents to the world. In Tolerance Is a Wasteland, Palestinian literary scholar Saree Makdisi writes about the long-standing practice of bringing visiting diplomats to the Holocaust memorial, Yad Vashem, where a walk through the museum ends with a bucolic view of the countryside—a vista dense with trees that the Jewish National Fund planted on the unmarked ruins of the Palestinian village Deir Yassin, where Zionist militias perpetrated a massacre in 1948. Suturing the undeniable trauma of the Holocaust to the expansive view of lush greenery, the memorial suppresses the state’s constitutive violence, summoning in its place Israel’s twinned sources of authority: Jewish victimhood and Jewish agricultural acuity. The addition of Volcani to this carefully curated diplomatic circuit extends this paradigm, in which agriculture is a technology of colonization, and technology is the grist of Israeli diplomacy.

For Florida, the value of these futuristic-sounding ag tech products is not wholly predicated on whether or not they work. Under Governor DeSantis, Florida, not unlike Israel, has faced potential isolation by the forces of liberal capitalism for its far-right policies: Since the passage, in 2022, of a slew of laws targeting women, immigrants, people of color, and LGBTQ people, the state has lost millions of dollars in canceled business conventions alone, and gone to war in court with Disney, by far its most important company. Like Netanyahu, DeSantis seems to hope that cultivating an image as a high-tech hub will keep his state enmeshed in global circuits of capital regardless of its glaring human rights violations; Florida’s business class has spent the last few years touting the idea of Miami as an AI hotspot and Tampa Bay as a Southern “Silicon Coast” (centers that, they emphasize, offer cheaper labor than Silicon Valley, along with a complete lack of income tax). A good deal of the tech strengthening Florida’s claim to these titles—from the crop protection company ADAMA Ltd. to the telecommunications manufacturer ECI Telecom, and from the software company Wix to the military technology company Elbit—comes by way of collaborations with the “Start-up Nation.” Along with the knock-on effects of its leaders’ cruelty, Florida faces the unavoidable crisis of climate change. As the state’s signature industries—agriculture, tourism, real estate—are coming under threat from flooding, hurricanes, and quieter human-made menaces like the blue-green algae blooms and discriminatory legislation, it is trying through technological solutionism to project the idea that everything is under control.

Standing at the top of the Citrus Tower in late December, I surveyed a landscape that has been harvested for centuries for its material and symbolic bounty. To the north, I watched a flock of birds circle what I knew to be Groveland, an infamous site of white supremacist terror. To the west, I looked down upon Lake Minneola, still vivid with blue-green algae. And as far as I could see stretched the ghosts of the orange groves, no longer present but still readily conjured by those seeking to assert domination over the land and those who live there.

Gavriel Cutipa-Zorn is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania. His research and writing engage histories of surveillance technologies and agribusiness. He lives in Philadelphia.