From Minneapolis to Jerusalem

On Black–Palestinian solidarity

MAY WAS A MIRROR. Almost a full year since the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis sparked revolutionary riots across the US and then the world, state violence inflicted on Palestinians in Jerusalem triggered protests that spread across Palestine—not just Gaza and the West Bank, but the entire terrain as it existed on the eve of the Nakba—and then the world. The Minneapolis-and-everywhere uprising of 2020 reanimated social life after a bruising first phase of pandemic. The Jerusalem-and-everywhere uprising of 2021, affirming the Lazarus power of riot, made tangible again the unity of Palestine, despite the balkanization of Gaza and the West Bank, the weakness of Palestinian political leadership, and the continuing horror of Israeli colonization.

As wealth consolidates among the super-rich and proletarian conditions lurch downwards globally, the situations of poor and oppressed peoples look less like heartrending exceptions and more like a shared status quo presaging a grim future. Early in the pandemic, George Floyd’s name became an inspiration and metonym for a widely shared vulnerability to state coercion and neglect. One year on, across different vectors, Palestine—its people corralled, tortured, dispossessed—briefly provided a universal channel through which protests expressed the hopes and fears of an evil time.

These two moments of collectively authored possibility did not arise from any recognizable political mainstream. Instead, recent protests have reintroduced an important element into the calculus of resistance, emphasizing the mass revolt as a political factor in its own right. The Palestinian protests of our present moment are given additional force by a transformation in US mainstream politics brought about by last year’s uprising. The events of 2020—the obscene knee on the neck, the burning of the Minneapolis precinct, the viral spread of riot all over—were felt around the world. This year, young Palestinian activists have cited the Floyd uprising as a guide and inspiration. Zionists have noticed the phenomenon too: A recent Haaretz op-ed by conservative journalist Jonathan S. Tobin, for instance, lamented the breakdown in US bipartisan consensus on Israel, directly blaming Black Lives Matter and the left wing of the Democratic Party.

The current phase of solidarity builds on the “Ferguson to Palestine” framework that emerged early in the Black Lives Matter movement, after the murder of Michael Brown in 2014. This earlier phase identified a shared enemy, materially grounding its analysis in the two movements’ experience of direct repression: the same tear gas, the same police training. As Angela Davis put it in a 2014 interview during the Ferguson uprising, comparisons between Ferguson and Palestine helped to illuminate the structural nature of state violence; these were not just local incidents of police brutality requiring local reforms, but nodes in a massive global network of repression. When the Movement for Black Lives released a political platform in 2016, it included condemnation of US collusion in Israel’s “genocide . . . against the Palestinian people.” Predictably, they faced a backlash from the white Jewish establishment. “We reject wholeheartedly the notion that effective anti-racist work can only be done by denouncing and excoriating Israel,” Rabbi Jonah Dov Pesner of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism said at the time: American Jews, in other words, should not have to choose between anti-racism at home and racism abroad in Israel. The activists who drafted the platform were unmoved by the argument that they should give a special ethical status to Israeli violence against Palestinians. American Jewish opinion moved instead. Despite the public anti-Zionism of the black movement, during the uprisings of 2020 all major Jewish organizations came out in support of Black Lives Matter.

After 2020, it’s clear that the militant abolitionist perspective arising from the black movement has lent young Palestinians new language with which to describe their circumstances, and that the movement’s growing ideological (if not material) dominance—even Donald Trump had to pay lip service to black uplift as he sent troops to crush the uprising last spring—has helped them find new confidence to use it. “The unabashed movement that spurred out of the George Floyd murder has forced itself within American discourse to articulate that we want to defund the police, we want to end policing, which is a conversation that hasn’t been [had] before on a mainstream level,” said the writer Mohammed El-Kurd, a leader of the movement to stop forced displacement of Palestinians in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, at a recent Zoom event. “Had it not been for that, we wouldn’t be here today regarding the global public shift in opinion regarding Palestine. People who are able to watch what’s going on in Sheikh Jarrah are able to see that a cop is a cop is a cop, anywhere in the world.”

Black struggle determines the level of struggle as a whole. The campaign to defund the police, for instance—an organizational gain made on the terrain of the riot—echoed through the vast recent pro-Palestine marches in the US. Placards read “DEFUND ISRAEL,” referring to the $3.8 billion a year the US contributes to the Israeli military. At a march in Brooklyn, young people came arrayed in flags and hopeful anger, riding motorbikes and scaling streetlights, the propulsive upward and outward force of the protest lapping against a shoreline of freeway and briefly stopping traffic. Cars draped in Palestinian colors revved their engines, producing clouds of smoke that blurred the crowd’s bright edges. Though the aesthetic of this spectacle was specifically Palestinian, the intensity of its claim—truth is beauty!—was reminiscent of black affirmations of particular joy amid general ruin.

ANALOGIES BETWEEN STRUGGLES are easy to make but their political meaning is often ambiguous. From the beginnings of Zionism in the late 19th century, some black radicals looked to its successes as an inspiration. “When the Jew said, ‘We shall have Palestine!,’ the same sentiment came to us when we said, ‘We shall have Africa,’” said Marcus Garvey in 1920. In 1948, the year of the Nakba, W.E.B. Du Bois praised Jews for “bringing a new civilization into an old land.” That same year, Paul Robeson said he would go to Palestine to perform for Jewish soldiers if war broke out.

The comparison between Zionism and Pan-Africanism was more sentimental metaphor than political stance; it made no real sense given the anti-imperialist commitments of these thinkers. But Zionist American Jews found it flattering and clung to it even as black support for Israel became less reliable. “By the late 1960s,” writes Marc Dollinger in Black Power, Jewish Politics, “Jews, thanks to black activists, could press for their own nationalist agendas without compromising their status as loyal Americans because Jewish affinity for the State of Israel aligned with the nation’s emerging identity-centered political culture.” Zionists reappropriated the Pan-Africanist analogy between blacks and Jews to argue that Jewish people were entitled to a home after generations of homelessness. The colonization of Palestine was perversely cast as the image of a historical restitution.

Despite efforts by pro-imperialist black leaders such as Bayard Rustin to sway black Americans in favor of Israel, by the late 1960s many black radicals no longer reciprocated white Jewish identification. They saw in Palestinian dispossession a more accurate mirror of their own situation than white Jews’ relatively frictionless access to social resources. Malcolm X had publicly condemned Zionism as early as 1958 and visited Palestine on several occasions. After his death, the continuity from the Nation of Islam’s early support for Palestine to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s (SNCC) embrace of the same position was the work of a former NOI member, Ethel Minor. She had joined SNCC after Malcolm’s assassination, bringing with her a passionate commitment to the Palestinian cause that emerged from her friendship with the Palestinian students she had met while attending the University of Illinois. At SNCC, while organizing in Alabama, Minor convened a Middle East study group whose members included Stokely Carmichael. By the time Carmichael assumed the chair of SNCC in 1966, he had spent two years intensively reading about Palestine and Zionism, thanks to Minor. It was Minor, too, who wrote the anti-Zionist position paper published in the SNCC Newsletter in 1967, the first public acknowledgment of SNCC’s allegiance to the Palestinian struggle. Support for Palestine became conventional among a substantial fraction of black American political organizations even as white consensus tilted further toward Israel.

Césaire’s understanding of the Shoah—not as the exception to European pseudo-universalism, but as its hidden rule—placed the destruction of Europe’s Jews within an ongoing and world-historical struggle on the field of race, class, and gender oppression.

Some black revolutionary thinkers saw the relationship between black struggle and the persecution of European Jews through the prism of a historical analysis that resisted the impulse toward idealization and analogy often present in other accounts. As early as 1950, the Martinican writer Aimé Césaire argued in his essay “Discourse on Colonialism” that it was no accident that the Holocaust was carried out by the same European bourgeoisie that had enslaved and exploited black and brown people all over the world: “at the end of the blind alley that is Europe . . . there is Hitler. At the end of capitalism, which is eager to outlive its day, there is Hitler. At the end of formal humanism and philosophic renunciation, there is Hitler.” This understanding of the Shoah—not as the exception to European pseudo-universalism, but as its hidden rule—placed the destruction of Europe’s Jews within an ongoing and world-historical struggle on the field of race, class, and gender oppression. It was an analysis diametrically opposed to the one that took hold in popular memory during the 1970s, when Zionists recast the Holocaust as a site of Jewish exceptionalism that licensed any amount of abuse in pursuit of a Jewish state. The post-’70s “Holocaust industry” tended to remove the genocide from its historical locus within the European struggle over fascism and communism, instead reifying it beyond recognition into a kind of ersatz spirituality of the abyss. Thus the potential overlaps between Jewish experiences of fascism and other struggles against imperialist domination were rendered inoperative compared to a Zionist narrative of salvation.

IN THEIR 1966 ESSAY “The City Is the Black Man’s Land,” writers and organizers James Boggs and Grace Lee Boggs describe black ghettos “policed by a growing occupation army.” The phrase reflected the black internationalist theory of black America as an internal colony, an oppressed state within a state, not dissimilar to the situation of Palestinians in Gaza or the West Bank today. In the same essay, the writers dreamed of an African American foreign policy mediated by black-led cities:

The black revolutionary government will make it clear in theory and practice that the Vietcong and the Black Power movement in the United States are part of the same worldwide social revolution against the same enemy . . . Moreover, speaking from a power base in the cities even before there is a national revolutionary government, black city governments are the only ones which could seriously talk with the governments of the new nations without resorting to the power which comes out of the barrel of a gun, as the United States must do today.

We can perceive in the present-day black movement’s contribution to the nascent shift in political consensus on Palestine something akin to the Boggses’ vision of a black foreign policy emanating not from the ossified organs of the state but from city-level organizing. Politics runs more on threat than on entreaty: Movements able to flood cities with thousands of energized, radiantly furious young people provide leftist Democrats with a potential power base from which to challenge American empire. (Few have done so.)

We can perceive in the present-day black movement’s contribution to the nascent shift in political consensus on Palestine something akin to the Boggses’ vision of a black foreign policy emanating not from the ossified organs of the state but from city-level organizing.

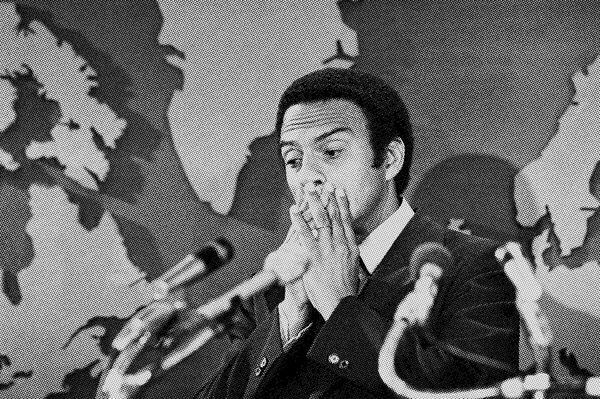

In 1979, the Palestinian predicament occasioned what could be thought of as an example of black foreign policy, precariously unfolding at the level of the state. Jimmy Carter appointed Georgia congressman Andrew Young ambassador to the United Nations. Young took seriously the task of representing a specifically black foreign policy, and accordingly he analyzed Israel’s relation to Palestine as one of oppressor to oppressed. Despite an official US ban on meetings with Palestinian politicians, Young privately met with a Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) representative, Zehdi Labib Terzi, in New York at the home of the Kuwaiti ambassador. When the meeting came to light, an outcry from American Zionists and threats from the Israeli government forced Young’s resignation. Explaining his actions to an interviewer, he said, “if you don’t have some other means of allowing [Palestinians] to express their grievances or affirm their rights, or define their rights, you’re going to get more death, more violence.” After his resignation, the blood-soaked theater of pseudo-peace negotiations continued as before, with most Palestinian parties either barred from the proceedings or stymied from the start by Israeli preconditions.

Despite his bravery in breaking with national policy, Young’s career also provides a disquieting example of the difficulty in integrating solidaric impulses into US governance. If black America represented an “internal colony,” then the limited successes of the civil rights movement were a partial decolonization producing a reactionary “under-developed middle class,” similar to those described by Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth. After the end of the colonial regime in recently independent nations, a professional class arose whose “innermost vocation,” in Fanon’s words, was “to keep in the running and be part of the racket.”

Young joined the US version of this racket when he implemented a series of neoliberal policies as mayor of Atlanta, a position he held for much of the 1980s. One plan he supported promised to create a “vagrant-free zone” downtown, a phenomenon the political theorist Adolph Reed describes as bluntly colonial, “a cordon sanitaire [meant] to protect revenue-producing, upper-income producers from potentially hostile confrontation with an indigenous rabble . . . The script for this scene was written when Great Britain marched into Calcutta and France sailed into Algiers, and it is reproduced daily in the Third World.” Through such colonial mechanisms, Reed argues, racial inequality is “built into the ‘natural’ logic of labor and real estate markets.” In both the US and Palestine, this logic is a central avatar of state power.

In Jerusalem today, where Palestinians in the neighborhoods of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan are fighting to remain in their homes, activists have been at pains to distinguish their state-sponsored displacement from the more mundane violence of real estate: “What’s going on in Sheikh Jarrah is actual ethnic cleansing and not an eviction,” El-Kurd has stated. The sentiment is understandable—El-Kurd wishes to resist the domestication of colonial assault into ordinary legal procedure. But, in the light of black struggle, it would be more accurate to put it the other way around: Real estate is a tool of ethnic cleansing not only in Jerusalem but in Atlanta, New York, and other US cities, where it is paradigmatically deployed against black people. As Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal of the Los Angeles Tenant Union has argued, there is a deep “enmeshment between the police state and the real estate state.” Breonna Taylor was murdered during a police campaign to evict long-term residents of her neighborhood ahead of a redevelopment project. The Israeli state mobilizes racist urban planning, civic legal processes, and settler vigilantism under the sign of a spurious security, a constellation of mundane horrors resembling the harrowing and displacing of black and indigenous people in the US.

Not just the spectacular violence of bombardment and street executions, but the everyday of work and housing, form the substance of the ongoing coloniality of both the US and Palestine.

For James Boggs, the colonial status of black American communities was revealed by their disproportionate exclusion from labor. Long-term unemployment, perennially higher among black people, produced ranks of “outsiders” whose relation to citizenship was abstract and remote: “Being workless, they are also stateless. They have grown up like a colonial people who no longer feel any allegiance to the old imperial power,” he wrote in his 1963 book The American Revolution. As people fall outside the social discipline of work, they become subject to state tactics of direct control—in this sense, at least on an abstract level, capitalist governance is always colonial in form, whether geared toward domestic or foreign populations. In Palestine, the link between unemployment and coercion is unambiguous: In the last quarter of 2020, Gaza’s unemployment rate was 43.1%. Not just the spectacular violence of bombardment and street executions, but the everyday of work and housing, form the substance of the ongoing coloniality of both the US and Palestine. This is the meaning of the recent Palestinian general strike, evoking a similar action in 1936: Colonial violence structures the working day as much as the checkpoint commute.

UNSURPRISINGLY, Israeli society has not been able to contain its racism to its passionate hatred of Arabs. Shocking anti-black barbarisms range from compulsory contraception for Ethiopian Jews to the incarceration of African refugees in megaprisons in the Negev desert. Though many black Israelis serve in the army and therefore directly assist in the colonization of Palestine, they often suffer racist abuse and are given the shittiest jobs. The 2015 death of IDF corporal Toveet Radcliffe—a 19-year-old from the Black Hebrew Israelite community in Dimona, which now faces threats of deportation—was ruled a suicide despite evidence of threats and harassment from fellow soldiers; in 2015, two white Israeli police officers were caught on video beating IDF soldier Damas Pakada in the street. Some aspects of the situation of black people in Israel, from disproportionate policing and incarceration to casual everyday racism, are not unique; the perception of blackness as fundamentally antagonistic to the state exists everywhere black people are a minority. But the disturbing harassment suffered by black migrants to Israel reveals that the demographic maintenance of its Jewishness cannot be disentangled from anti-blackness. “If you bring in a million Africans, [Israel] will no longer be Jewish,” then-Knesset member Michael Ben-Ari said in a 2010 interview, explaining his leadership of a hate campaign persecuting black refugees. “The Sudanese are a cancer in our body,” concurred the Likud politician Miri Regev, using a phrase usually reserved for Palestinians.

Anti-blackness is not confined to white Israelis. There is no more point in flatly ignoring the presence of anti-blackness within Palestinian society than there is in deploying it to dismiss points of contact between black and Palestinian struggle. A seam of Afro-Palestinian continuity runs all the way back to slaves brought to the area during the Ottoman era, and the historical wound appears in epithets and attitudes as it does elsewhere. In Afropessimism, Frank Wilderson recalls a Palestinian friend’s account of his experiences of military harassment, which he says cause him deeper “shame and humiliation . . . if the Israeli soldier is an Ethiopian Jew.” It is impossible to disagree entirely with Wilderson that, on a symbolic level, “blackness is a locus of abjection to be instrumentalized on a whim.” As he and others have highlighted, and recent black public discourse has affirmed, any discussion of or material attempt at solidarity has to address the problem of anti-blackness. Not doing so leaves our struggles open to reactionary uses of identity politics—to put it simply, when the politics of a revolutionary movement are articulated primarily by non-black people, the movement can be easily overturned by liberal pretenders to black authenticity—or misrecognizes the task of solidarity as a project of eliding social antagonisms. The 2020 uprising has helped to reframe these anxieties of solidarity: Clearly both multiracial and directed by black struggle, it once again highlighted that the horizon of black liberation should be a motivating force for solidarities, rather than a barrier. At protests and talks this spring, the dominant note between black and Palestinian activists was one of mutual admiration and gratitude.

Two possible futures can be conjectured: Either the continuation of an increasingly fascistic, exclusively Jewish state conjoined to the open-air prison of Gaza, or a democratic, integrated Arab and Jewish state that may or may not be called Israel or Palestine. The latter would be the salvation of Israel, otherwise condemned to the kind of social decay you might expect under apartheid conditions. Who is tasked with this salvation? In the US, whatever possibility there is of national redemption, of the abolition of America as it is and its recreation as it could be, inheres in black America. (James Boggs dreamed that the black revolution would culminate in a constitutional convention.) Similarly, it is only the presence of Palestinians that now keeps alive the possibility of making a demos out of the disaster of Israel. Brutalized beyond belief, there is no reason for Palestinians to choose this path over those of destruction or despair. That they still strive to do so, through protest, through resistance, through ongoing unity, is an act not of violence but of grace.

Hannah Black is a writer and artist. She was born in Manchester, England, and lives in New York.