Fear Is Not a Good Principle

A Minnesota school desegregation advocate reflects on a life spent fighting.

FOR THE FIRST TIME in many years, court-ordered desegregation is generating national headlines. The most heated moment of the June 27th Democratic presidential primary debate in Miami came when Kamala Harris unapologetically criticized Joe Biden for his past efforts to derail integration. Harris, who is black, noted that she herself was bussed as a young girl as part of an effort to integrate Berkeley public schools.

Reporters immediately dug in, analyzing the social science research on segregation, the available legal options for pursuing integration, and the stubborn historical myths about how it worked in the past. But while many Americans are just waking up to the topic, squinting and bleary-eyed at what they could have sworn was just a 20th century footnote, one woman living in Minnesota is hardly fazed.

Tucked away in the cozy Bryn Mawr neighborhood of Minneapolis lives 84-year-old Barbara Bearman, who has been actively working on school desegregation for more than five decades. She’s been involved with three separate lawsuits to integrate her city’s public schools, with the latest one filed in November 2015. The plaintiffs for that ongoing case, Cruz v. Guzman, scored a victory last summer at the Minnesota Supreme Court, and are now in mediation.

“Barb was with us when we filed our Minnesota desegregation case in 1995, and the one we filed in 2015, twenty years later, she helped us find people willing to be plaintiffs,” says Daniel Shulman, the lead attorney on both suits. “You can’t do anything more important than that. She’s been in constant communication with us, she always has ideas. If I had one word to describe her and civil rights it’s ‘indefatigable.’”

Bearman’s tireless focus is wrapped up with her complicated Jewish identity. Growing up in Minneapolis, she remembers being active in United Synagogue Youth, attending “Council Camp” (run by the National Council of Jewish Women) during the summer, and being reprimanded regularly by her Hebrew school teacher. “I just wouldn’t shut up and apparently I wasn’t a dedicated Hebrew learner,” Bearman says with a laugh.

She didn’t stay involved with Jewish organizations as she grew older, but says she feels Jewish to her core, and expresses her religiosity through ethics and civil rights.

“You want to know who my Jewish idol was? The only thing I can remember from Sunday school?” she says. “Abraham breaking the idols.”

While Bearman’s Jewishness has undergirded her activism, Jewish groups in the Twin Cities never got very involved in school desegregation, a fact that both Bearman and Shulman recount with frustration. “It’s a disappointment,” says Shulman.

“Jews weren’t involved,” says Bearman. “I don’t associate it with Jews.”

It was the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 that propelled her own involvement. That year, Bearman help co-found the Committee for Integrated Education, a volunteer group that worked with the local NAACP chapter to pressure the Minneapolis School Board to desegregate its public schools. When their efforts for voluntary action failed to gain traction, they recruited an attorney, Chad Quaintance, to file suit against the district.

Quaintance was a civil rights lawyer who had previously litigated desegregation cases for the US Department of Justice in Alabama and California. He had recently moved to Minneapolis, where he lives to this day.

“She was fantastic, high-energy, very smart and hardworking,” Quaintance tells me, describing how Bearman helped him gather and analyze research about the city’s school system. “Maybe the lawsuit would have happened without her, but she was a very significant part of the case.”

That lawsuit was Booker v. Special School Dist. No. 1, and in 1972, Minnesota’s Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, finding the Minneapolis school district in violation of the 14th Amendment for its segregated schools. The segregation was partly due to residential housing patterns, but was also caused, the judge found, by intentional decisions from school district leaders. For example, the school district continued to add classrooms to overcrowded and predominantly black schools, while nearby white schools remained under-enrolled. While nonwhite students then amounted to less than 10% of Minneapolis’s student population, they comprised more than 70% of the enrollment in just three schools. More than 11,000 students were eventually bussed as part of the court order, which remained in effect until 1983.

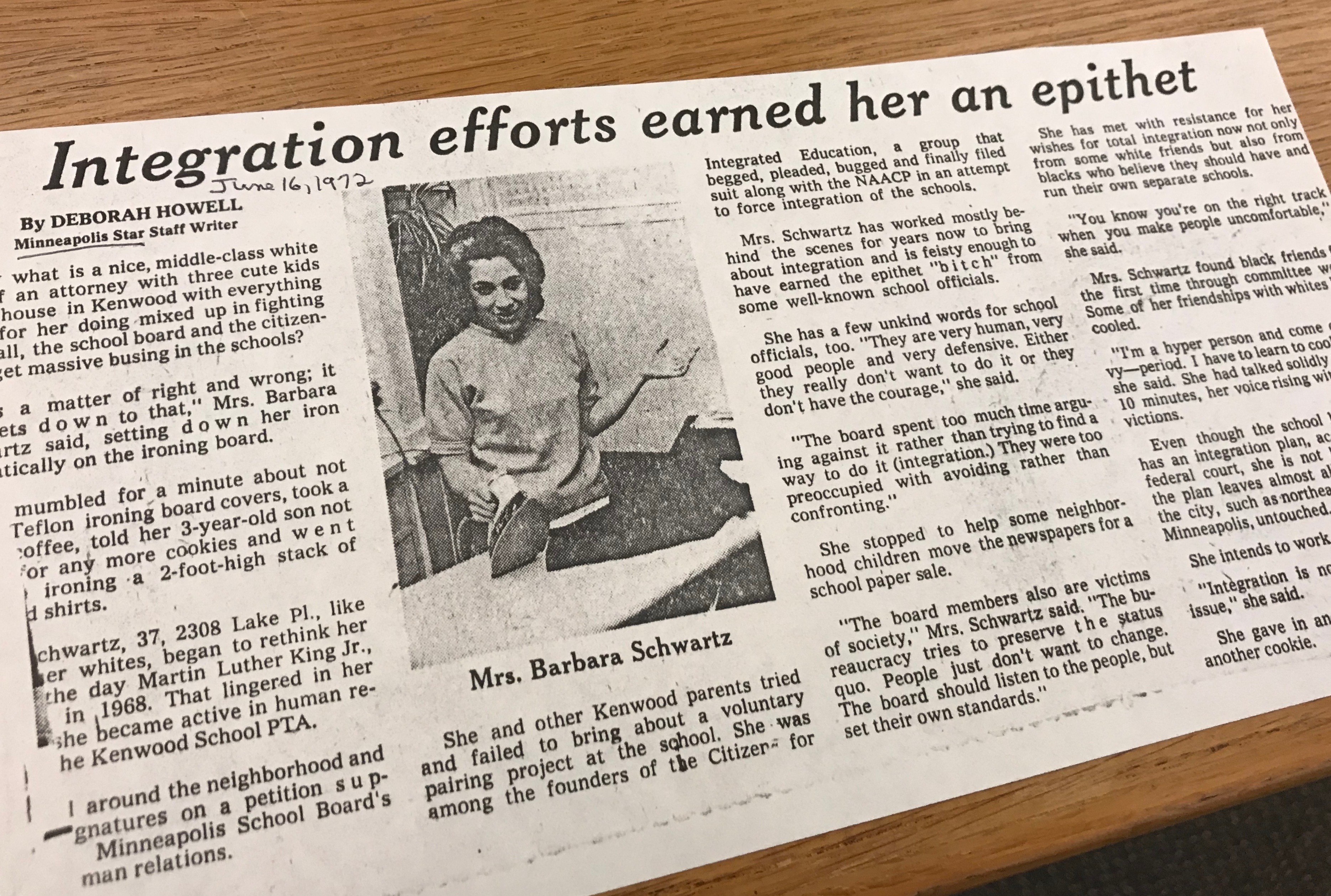

To some, Bearman’s commitment to school integration was perplexing, even exhausting and irritating. “Now what is a nice, middle-class white wife of an attorney with three cute kids and a house in Kenwood with everything going for her doing mixed up in fighting city hall, the school board, and the citizenry to get massive busing in the schools?” a 1972 Minneapolis Star article began. The piece reported that local school officials often called Bearman a “bitch” because of her advocacy.

Bearman regularly wrote letters to newspapers, collected petition signatures, convened meetings, and escalated political pressure wherever she could. Some of her friends eventually grew tired of this and stopped talking to her.

“I don’t know, I just had this drive, and that’s why I was called a bitch,” she tells me. “I had a big mouth, I know I came out like a sledgehammer to everybody, I’m sure. But you just don’t compromise on this one.”

Boxes at the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul contain records upon records documenting Bearman’s involvement with local desegregation efforts—from legal correspondence linked to the Booker case, to school board meeting minutes, to a host of district planning documents and reports. Bearman also spent decades as an active member and officer of the city’s NAACP chapter. When Minneapolis schools started to resegregate, beginning in the 1990s, due to lawmakers easing up on civil rights enforcement and elevating school choice policies, Bearman worked with the NAACP to file another suit.

Most of the racial justice activists Bearman worked most closely with have since passed away, and when she reflects on her life, she says she recognizes her dedication to desegregation sometimes caused her to miss out on other things going on in her home and community.

“But if I wasn’t being headlong . . . well this takes a lot of energy—it takes a lot of psychic energy to keep going against all odds,” she says. “If you stop too much and consider walking away, well, that’s not how I was operating. Throughout my life, I could be a slow starter, but once I started, then I boarded in.”

For Bearman, even to walk away now, as the Cruz v. Guzman case marches on, would amount to a betrayal of herself. “I’m not perfect, but I’m most proud of the things I’ve stayed true to,” she explains.

As to whether she’s surprised that school integration has resurfaced in our national politics, she shrugs. “It’s like antisemitism,” she says. “These issues never really go away, they just exist right under the surface, and certain things can bring them into focus.”

What’s needed now, Bearman says, is what’s always been needed—courage. She hopes our political leaders will educate themselves and buck up. Racial integration “gets to the very heart of what this country is and what we say this country stands for,” she says. “At the end of the day there is just so much fear, and fear is not a good principle on which to live.”

Rachel Cohen is a Washington, DC-based freelance journalist and a contributing writer for Jewish Currents.