Exodus: Beshalach

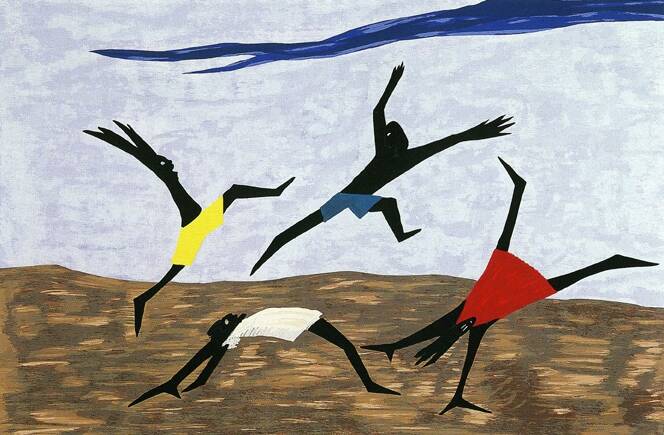

For the enslaved, the formerly enslaved, and the otherwise surveilled, wandering is not simply unproductive movement; it is self-possessed, erratic, wayward action.

Read previous entries of Slow Burn: Quarantine Edition here.

Beshalach

Exodus 13:17 – 17:16

Portland, OR

Dear friends,

I have taken to wandering lately. I’ve had to. My apartment is small and clumsily decorated, if shoving a few prints and museum gift shop postcards into IKEA frames and throwing them onto eggshell white walls even counts as decorating. I’ve tried to alleviate my anxieties about certain world events and add a little color to my life by ambling about the small, intimate rose gardens in Ladd’s Addition, a residential development in southeast Portland. Meticulously planned in the 1890s, the neighborhood feels designed to make one lose one’s sense of place. The smaller gardens connect to a larger public space ensconced inside a traffic circle that leads out into so many roads, even the most confident traveler can be made to feel like a somnambulist.

These strolls are necessary—they tether me to a world that I thought I knew, one that seems to vanish with each consecutive day that I stay inside—but they are not safe. Though Oregon’s stay-at-home order has been looser than those implemented in harder-hit areas like San Francisco and New York City, I am under no delusion that my sojourns will go unnoticed. Statistics show that African Americans have been disproportionately policed for simply being outside during this time. And while hundreds of primarily white protestors, supported by a network of conservative groups and sometimes armed, wander over to state capitol buildings demanding that black and brown people work so that they may get haircuts, the association between movement and freedom continues to be racialized along the usual, well-rehearsed lines.

I am acutely aware of all of this. But I still stroll among the roses because it is during these walks that I can chromatically daydream outside of the confines of my beige and bare apartment. In Wandering: Philosophical Performances of Racial and Sexual Freedom, the critic Sarah Jane Cervenak argues that, especially for black women, wandering “sustains an unavailable landscape of philosophical desire.” For the enslaved, the formerly enslaved, and the otherwise surveilled, wandering is not simply unproductive movement; it is self-possessed, erratic, wayward action that refuses to map straightforwardly onto the human geographies designed according to Enlightenment principles of reason, transparency, and legibility. In his essay “The Case of Blackness,” the theorist Fred Moten calls this kind of motion fugitive movement—“a movement of escape, the stealth of the stolen that can be said, since it inheres in every closed circle, to break every enclosure.” Fugitive wandering might seem like a paradoxical kind of motion: Why move slowly and aimlessly if you are trying to not be captured? For Cervenak and Moten, the answer is twofold. Moving without immediate purpose can enact freedom of movement where it did not previously exist, but it is also tactical. It constitutes an alternative method of sense-making that frustrates logic by appearing illogical.

Beshalach, the fourth parsha of Exodus, narrates the beginnings of the Israelites’ decades-long wanderings out of bondage and into the wilderness—another case of slow, seemingly directionless movement. As they approach the Red Sea, the Israelites ask Moses why they have left a life of subjugation in Egypt only to die at the hands of their former oppressors in the desert. But God has a plan: He instructs the Israelites to perform fugitive movements as a ruse to evade the army chasing them down. As God tells Moses, “Pharaoh will think regarding the Israelites, ‘They are wandering around confused in the land—the desert has closed in on them.’” The act of wandering is a tactic that thwarts reason and lulls the oppressor into a false sense of security: Only a people made delirious by desert travel, Pharaoh assumes, would think to place themselves between their enslavers and the sea. He is wrong, of course. Moses, under the guidance of God, parts the sea, allowing the formerly enslaved to cross and drowning the Egyptian army behind them.

Celebrating their successful first performance of fugitivity, the Israelites sing God’s praises: “In Your love You lead the people You redeemed; In Your strength You guide them to Your holy abode.” In his letter on the first parsha of Exodus, Dan remembers singing a variation on these lyrics around a bonfire as a Bible camp activity meant to build and strengthen bonds among the campers through shared devotion. The song serves a similar function in Beshalach, invigorating a sense of camaraderie through communal exaltation. Once the Israelites are on the other side of the sea, however, they return to their former skepticism, lamenting that their divine protector has left them with nowhere to go and nothing to eat: “If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots, when we ate our fill of bread!” When I was a child in Sunday school, I learned that these complaints were illegitimate and rebellious; God told the people He would provide, and so they should have trusted Him—and indeed, within 24 hours, He gives them quail and manna, which they will consume for the next 40 years. Reading the Israelites’ roaming in the wilderness in this way serves as the basis for an aphorism of religious orthodoxy: Even when it feels like God has abandoned us, we must have faith that He is at least guiding us somewhere.

Reflecting on the parsha on my walks around the rose gardens of Ladd’s Addition, I came to a different conclusion. The Israelites’ complaints can be read not as expressions of heresy, but rather as one of the first moments in which they assert themselves as a community. “[Y]ou have brought us out into this wilderness to starve this whole congregation to death,” they tell God. Without knowing when, if ever, they will arrive at the Promised Land, the newly self-anointed “congregation” begins to construct itself not only as a group of fugitive wanderers, but as a people unwilling to subject themselves to a new Pharaoh without corroboration of His ability to provide.

If we understand the Israelites in Beshalach as proclaiming their subjectivity after centuries of abjection in Egypt, this long period of wandering becomes an end unto itself: it affords them the time and the space to construct a group identity and negotiate a working relationship with God. In this parsha, the Israelites occupy an interstitial space between object and subject, slavery and freedom—and their shift from one position to the other must be realized beyond the purview of the Egyptians. They cross the Red Sea not only to break the chains of enslavement but to finally exercise kinetic agency. Wandering begins as a method of escape, but once the Egyptians are left behind, it marks an aspect of freedom, an enactment of fugitive subjectivity. For the Pharaoh, the Israelites’ being was inextricable from their labor: deliberate, productive, goal-oriented activity. By engaging in unhindered, directionless movement, the Israelites disrupt this premise without immediately replacing it with a different one. In wandering, they ask: Who are they for themselves and in the eyes of God?

Beshalach takes place after God has chosen the Israelites as His people but before they have entered into a covenant with Him on Mount Sinai, the time between being chosen and consenting to the choice. It is under these conditions that they begin to choreograph what freedom as a religious subject looks like, well before they reach their destination—and in this parsha they attempt to establish a dialogic relationship with God instead of permitting him to act as an authoritarian leader. In this way, the Israelites’ complaints can be read as vocalizing the state of fugitivity itself: a perpetual unfolding of subjectivity that refuses to adhere to the limitations of law or the boundaries of propriety. When they articulate themselves as an assembly, a community disjointed from Egyptian rule, their wandering stops being a criminal act and becomes an existential mode. This is perhaps the moment when diaspora begins.

I have left freedom undefined—is it the absence of oppression? the presence of autonomy? —because I feel like my already-tenuous grasp of the subject has fallen away from me in these chaotic times. Blackness has always vexed notions and definitions of freedom, but the rules of the game feel particularly unstable right now. As those right-wing protestors mark stillness and inactivity—often the charges made against enslaved people—as tyranny, Ahmaud Arbery has been murdered while wandering on a jog through a neighborhood near Brunswick, GA. While angry demonstrators advertise a vision of conspicuous consumption as the apex of liberation, Breonna Taylor has been killed in her own Louisville, KY, home, resting from her already perilous job as an EMT worker. If neither being outside nor inside affords black people a sense of safety, I guess I’ll continue to move without moving in order to maintain a sense of self in this new world that rapidly builds upon the same old inequities.

Love,

Omari

Omari Weekes is an assistant professor of English and American Ethnic Studies at Willamette University.