Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville, Texas, in April 2022.

Beyond Grievance

Though it may be a potent political tool, grievance can also maintain our investment in our own oppression.

Responsa is an editorial column written by members of the Jewish Currents staff and reflects a collective discussion.

Two weeks into this patently miserable year, a British Pakistani gunman took four worshippers hostage at a Reform synagogue in Colleyville, Texas. If you logged on amid the 11-hour standoff, you might have been forgiven for thinking that the true crisis was not that people were being held at gunpoint in a place of worship, but rather that the story had failed to meet an indeterminate threshold of concern on Twitter. Even as scores of non-Jewish leaders quickly spoke out online against antisemitism, and organizations, particularly Muslim ones, rushed to release formal statements condemning the attack, a significant number of Jews railed against what they perceived as a familiar slight, reigniting the debate about where antisemitism fits into a supposed hierarchy of oppressions. When FBI special agent Matthew DeSarno said the attack was “not specifically related to the Jewish community”—a claim that was picked up by AP and the BBC—many asked if violence against any other minority group would suffer the same misdiagnosis. If the hostages had been Black, they began, resentfully conjuring a fantasy of tearful, wall-to-wall coverage. The same critics felt vindicated the following day when the incident failed to appear on the front page of The New York Times’s print edition.

The concern at being overlooked quickly devolved into a communal tantrum, even as the crisis itself resolved with all hostages returned to safety. This was followed by a petty accounting of the number of minutes devoted to the incident on cable news, or its relative placement in national newspapers. The outrage swelling on social media crested in the paper of record when the conservative New York Times columnist Bret Stephens posited that Jews were in fact suffering a double victimization: “First, by being physically targeted for being Jewish; second, by being begrudged the universal recognition that we were morally targeted, too.” Elsewhere in the opinion section, famed Holocaust scholar Deborah Lipstadt—whose nomination for US special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism was stalled in the Senate—scolded gentiles for their callousness: “This week we wonder if the eyes of our non-Jewish friends and neighbors, particularly the ones who didn’t call to see if we were OK, have been opened just a bit.”

But Jews were not being ignored; in fact, the response was swift and substantial. The FBI corrected the record; its director, Chris Wray, soon appeared at an ADL event alongside Colleyville rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker. The media followed suit, with major networks devoting airtime to interviews with the hostages. Colleyville was front-page news in the Times on January 17th, less than 48 hours after the hostages’ escape. (It had already been “breaking news” at the top of the mobile and digital editions.) Assertions of neglect shriveled further in light of their own proliferation in mainstream media: Besides Lipstadt and Stephens’s op-eds in the Times, James McCauley took to The Washington Post to call on American lawmakers to prioritize the fight against antisemitism and confirm Lipstadt in the Senate. (She has since been confirmed.) Writing in The Atlantic, Yair Rosenberg addressed what he saw as the failure of broad cross-sections of the American public, including tech platforms and anti-racism activists, to grasp antisemitism’s unique contours. Meanwhile, in Vox, Zack Beauchamp offered a warmed-over version of British comedian David Baddiel’s “Jews don’t count” argument, which posits antisemitism as an undervalued bigotry—the rhythmic gymnastics of today’s oppression olympics. (It should be noted that the progressive magazine The Nation could not run a piece like this, having published an article with roughly the same angle, apropos of nothing, only a few days earlier.)

A graphic from an aish.com Instagram post. The accompanying text read “If you’re Jewish, somebody hates you. That’s always been true, and it’s intrinsic to who you are.”

Likewise, support from the authorities kicked into gear. Some local police precincts stepped up precautionary patrols around synagogues in other states. At the federal level, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, Attorney General Merrick Garland, and several other administration officials joined a briefing a few days after the attack with representatives of more than 1,500 synagogues and Jewish organizations, where they made “very clear, strong statements identifying this as an antisemitic event that targeted the Jewish community,” according to Nathan Diament, executive director of the Orthodox Union Advocacy Center. Conference of Presidents CEO William Daroff concurred that “engagement by the administration, by the Justice Department, Homeland Security, and the White House has been remarkably helpful and remarkably cooperative.” This coincided with a push in the Senate to increase funding for the Nonprofit Security Grant Program—which funds safety measures for houses of worship and has distributed the vast majority of its grants to Jewish organizations—from $180 million to a cloying double chai. (Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville had already received the maximum grant of $100,000 in 2020, which Jewish Insider reports it used on “contract security, lighting, cameras, fencing, an entry gate, and ‘management and administration.’” They had also received active shooter trainings from the ADL, the FBI, and the Secure Community Network, which Cytron-Walker credited with the hostages’ survival.)

Given this response from media, government, and civil society in the week following the attack—and the fact that our institutions already have significant resources to spend on the trappings of security—it’s not surprising that Jewish identitarians found themselves with few targets and even fewer demands. What stood in place of a coherent analysis of antisemitism or a list of actionable responses was a general posture of grievance, a diffuse call to be noticed, crystallized by Beauchamp in the conclusion to his Vox essay: “What American Jews need from mainstream American society right now is to be listened to, for our fears about rising anti-Semitism to be heard and, once heard, taken seriously on their own terms.” While the blanket claim of “rising anti-Semitism” is difficult to verify absent any baseline of comparison, it seems clear that we are witnessing a surge of organized white nationalism and a coordinated campaign in support of Christian rule. And still, according to a 2020 Pew study, the percentage of American Jews who self-report a sense of rising antisemitism—75%—is outmatched only by the percentages upwards of 85% reporting high degrees of physical, social, and economic well-being. This disjuncture between our anxieties and the material realities of our lives suggests that the fear is not a direct response to present conditions, but a compulsion rooted in some unseen terrain, making the call to meet it “on its own terms” impossible to fulfill.

The public response to Colleyville suggests that for many this story has become a passion play, a rehearsal of suffering and isolation intent first and foremost on maintaining itself.

A relationship to oppression and otherness has been central to Jewish identity since the beginning of our formation as a people; Jews who agree on nothing else agree that we have repeatedly been strangers in strange lands. But the public response to Colleyville—the performance of a crude identity politics without the politics—suggests that for many this story has become a passion play, a rehearsal of suffering and isolation intent first and foremost on maintaining itself. I do not blame Jews for feeling fear and sadness in response to an attack on our places of worship—I felt those things, too. There was a leaden knot in my stomach those long hours of the standoff; when the hostages escaped, I wept. I craved ritual, cobbled together a solitary, makeshift havdalah with a Hanukkah candle, an orange, and a glass of beer. I felt something, and that feeling was a burrow into a thing I call Jewishness, a nurturing of kinship and acquaintance with my ancestors, with their fear and their survival. But what would it mean to metabolize those feelings, instead of chewing them like a bitter cud? What could healing do for us?

IN THE DAYS AFTER COLLEYVILLE, amid the hasty communal J’accuse, I read Anne Anlin Cheng’s 2000 book, The Melancholy of Race. The book charts the divergences between grievance and grief as responses to racial injury: Grievance, characterized by an appeal to an outside power, does “important political work” for the minoritized group, Cheng asserts in an interview with BOMB. But she questions its primacy at the expense of grief, a mode that might transform the internal landscape of the self: “In our eagerness to articulate grievance, we forgo some of the deeper mourning processes that are required to deal with the legacy of that grief.” The book takes as its starting point a line from Robert Frost: “Grievances are a form of impatience. Griefs are a form of patience”; Cheng argues emphatically “for doing that work of patience, of grieving, which may not appear as immediately satisfying as grievance but . . . may do more profound work in the long term.”

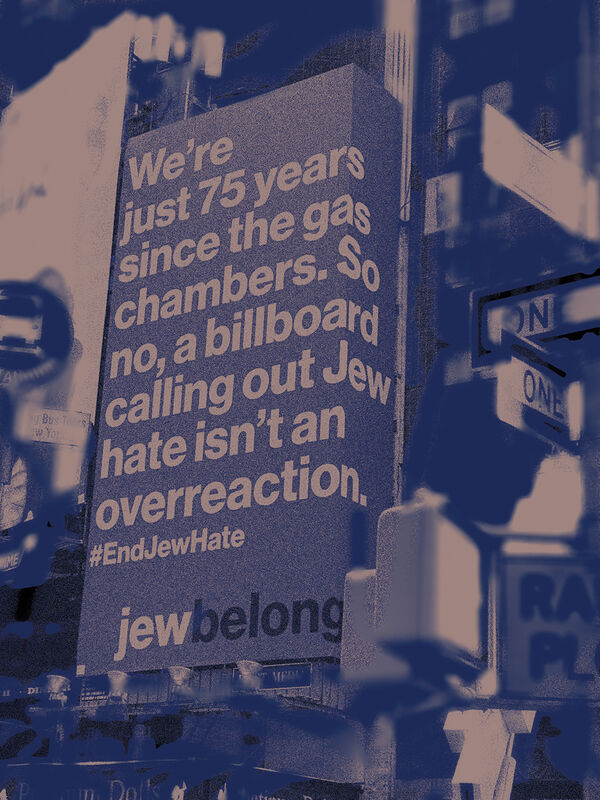

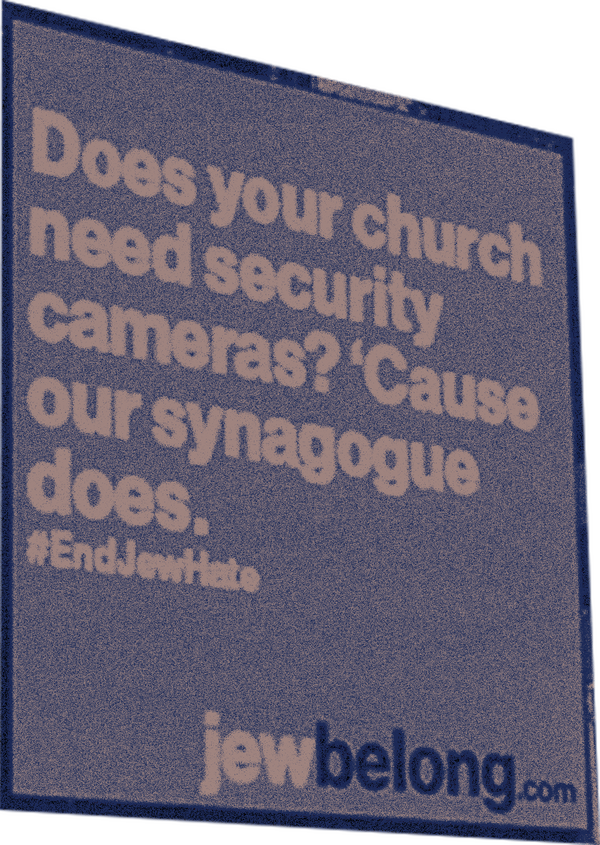

Anti-antisemitism billboards in Times Square, New York City, 2022.

To illustrate the dangers of forgoing grief, Cheng takes as a foundational text Freud’s classic 1917 essay “Mourning and Melancholia,” in which he distinguishes between “mourning”—a healthy response to loss or rejection, where the object of loss can eventually be relinquished and the pain overcome—and “melancholia,” where the mourner becomes psychically stuck in a refusal to get over the loss. Of course, the self would not suffer this overattachment to loss if it was not also benefiting from it; indeed, Freud identifies this unhealthy attachment as an incubator for the ego, which repeatedly gorges on the loss until it is entirely incorporated into the self. In this way, Cheng explains, the mourner “grows rich in impoverishment.” The self, now constructed on a foundation of loss and exclusion, is compelled to protect itself, making sure that “the ‘object’ never returns, for such a return would surely jeopardize [its] cannibalistic project.” Thus, “although it may seem reasonable to imagine that the griever may wish” for a resolution, for the object of loss to be restored, “the ego may in fact not want or cannot afford such homecoming.”

Reading this text, I felt a surge of recognition, an explanation for why, in my most cynical moments in the days following the Colleyville attack, I was certain I perceived pleasure in the collective complaint. Pleasure in being noticed, for once, as innocent victims, instead of suffering the moral injury of being cast as emissaries of Israeli apartheid or standard bearers of white privilege. Pleasure in the opportunity to be seen by the world as we see ourselves. This was a role we were born to play! We were slaves in Mitzrayim! Burned up at Auschwitz! Cast out of every Arab land! This attack was just another identifiable plot point on an unbroken circle drawn in ash; it was the same eternal threat, with the same annihilative intent, carrying the same unit of emotional weight.

At what point does asserting antisemitism’s unsolvability tip into not wanting it to be solved?

I began to wonder if this melancholia, this inability to mourn, was interfering with our ability to know and address the problem of antisemitism itself. If antisemitism is a permanent, transhistorical ill—“protean and primordial,” as Beauchamp calls it in Vox—why bother with material solutions? It is in antisemitism’s persistence where meaning is found, after all. It is a connection to an ennobling legacy—to our past, to ourselves, and to one another—that has proved much stronger than any religious belief. Filled with this threat, our institutions bloat like balloons. Is it any wonder that those who ring the alarm bells are asking for nothing more than “acknowledgement”? At what point does asserting the problem’s unsolvability tip into not wanting it to be solved?

I KNOW WHAT IT’S LIKE to be in thrall to historical pain. In 2018, Jewish Currents Contributing Editor Maia Ipp and I—both grandchildren of Holocaust survivors—published a series of letters in this magazine in which we laid out our discrepant approaches to Holocaust memory. “You talk of having moved through, of healing,” I wrote to Ipp. “Fuck that . . . What does carrying this legacy mean if not carrying the pain? Isn’t the pain, alive in us, what makes it real and alive, what makes it more than a story?” The occasion of the letter finds me afraid to heal, lest I lose the meaning of my family’s suffering and its role in the story of who I am: When the pain “will be ordered, intellectualized, processed, healed, it will also be sanitized, and therefore meaningless.”

But Ipp resists my investment in suffering: “If pain is the primary mode of meaning-making, determining a hierarchy of suffering seems inevitable, which we know leads in dangerous directions.” She discusses her own path to healing, a kind of support group for children and grandchildren of survivors that she attended for nearly a decade, where they spent time “not just talking in circles, but feeling into how this legacy impacted us.” She describes the difficult work of mourning: “I often had to force myself against all desire to participate, to even show up; it was excruciating sometimes, the grief that appeared once we had made a space to hold it.” When she eventually made her way to Europe, she expected the emptiness, but she did not expect the joy. She began a dialogue group with descendants of Nazis; her investigation into grief had led her to find solidarity precisely where it shouldn’t have been. “I could feel how the Jewish absence was a force on the people I met, how much pain they felt too,” she writes. This discovery didn’t negate the pain, but it did change how she related to it: “I believe that there’s a relationship to this legacy which contains pain but isn’t defined by it: the pain neither repressed nor sanctified, but given the attention it needs without being seen as the primary way of knowing, representing, or attaching.”

Anti-antisemitism billboards in Times Square, New York City, 2022.

I struggled then as now to assimilate Ipp’s perspective; I cannot claim to have healed. But I cannot deny that to take the pain for granted as a constant is also to will it into being, to deaden an awareness of the present in favor of a reenactment of the past. And I wonder what it would have been like to grow up in a Jewish community that privileged and facilitated the experiences that Ipp created for herself: group work dedicated to feeling and ultimately releasing the pain and to connecting with non-Jews, integrating them into the frame of the Jewish story.

Perhaps it seems a tall order to imagine communal healing on this scale. But consider how reliably Jewish communities have integrated elaborate reenactments of episodes from the canon of ancestral suffering into the Jewish educational curriculum. I myself participated in a range of these at summer camps and on Israel trips, replaying the decisions made by the Judenrat in the lead-up to Nazi deportations, the clandestine attempted incursions into Mandate Palestine by Jewish refugees (enacted from an ocean liner off the shore of Haifa, no less), and capture by an Arab enemy during an unnamed Israeli war. (A friend who was “taken hostage” by surprise in this latter reenactment, at an IDF base during a Birthright trip, had recently been mugged and choked unconscious in Brooklyn; the reenactment provoked a significant episode of PTSD.) Many millions of dollars are being poured into a Jewish politics of fear; it’s not so far-fetched to imagine how curricula of healing could be institutionalized and dispersed instead.

Many millions of dollars are being poured into a Jewish politics of fear; it’s not so far-fetched to imagine how curricula of healing could be institutionalized and dispersed instead.

DISCUSSING THE WAY Jews have refused mourning in favor of a politics of grievance, it’s tempting to locate the problem in the content of the complaint, but not its form. To say, in essence, that largely white and well-off Jews are abusing the tool of grievance—fluently speaking the language of marginalization with the access and entitlement afforded by power—while groups experiencing greater degrees of marginalization are simply using it appropriately. After all, Jewish grievance in particular must continually overlook the support coming from the state—here and in Israel—in order to justify its cries of neglect, while for many other groups, the state is the source of harm. And for those groups, grievance remains a politically useful form of redress. Even Cheng, who questions its dominance, its dubious assumption that all “injury can be quantified and verified,” admits that grievance is also “probably the only thing that has affected social change in the last fifty years.”

But while the left has become more and more invested in foregrounding grievance in the name of justice—in organizing spaces, in institutions, and especially on social media—we do not appear any better situated to hold power to account. If anything, the opposite is true: As our gerontocracy ignores us, we often turn the tools we have sharpened to fight it against one another, where we meet with more “success.” The philosopher Olúfémi O. Táíwò has argued convincingly that the sanctification of trauma and pain, and their wholesale attachment to broad racial categories, has been a corrosive force in our organizing, placing “the accountability that is all of ours to bear onto select people—and, more often than not, a hyper-sanitized and thoroughly fictional caricature of them.” This creates “moral cowardice” among people in the habit of “deferring” to those deemed more oppressed, and a lack of accountability for those being deferred to. Ultimately, this approach, he writes, “ask something of trauma that it cannot give”: It equates the trauma state, which is by nature “partial, short-sighted, and self absorbed,” with greater wisdom, thereby obviating the need for healing. But pain, he writes, is in fact a “poor teacher”: “Oppression is not a prep school.”

Táíwò is concerned about the ways this opens the door for cooptation in the form of what he calls “‘elite capture’: the control over political agendas and resources by a group’s most advantaged people.” “Such treatment of elite interests,” he writes, “functions as a racial Reaganomics: a strategy reliant on fantasies about the exchange rate between the attention economy and the material economy.” But he appears most concerned about the potential for these practices to create divisions precisely where coalition is the aim. He insists that all politics is at heart coalitional politics—a process of forging common interest across difference—and thus that the “deferential orientation, like that fragmentation of political collectivity it enables, is ultimately anti-political.” If trauma confers wisdom, if it makes us worthy of being listened to, why would we ever want to let it go? And if coalitional politics could provide a way out, no wonder we seek to shut them down. No wonder, to paraphrase Cheng, we speak the language of isolation cloaked in the language of solidarity.

Once you notice these melancholic patterns—the libidinous attachment to suffering supplanting real political aims—you find them in every group that has built a kinship on shared pain.

Once you notice these melancholic patterns—the libidinous attachment to suffering supplanting real political aims—you find them in every group that has built a kinship on shared pain. They provide an explanation for why our left spaces, filled with those driven by the desire for justice, continually tear themselves apart with grievances unequal to the dimensions of the threat we are facing. In this regard, Jews appear not as opportunists appropriating the tools of the oppressed, but as one cautionary tale among many about the identitarian enshrinement of suffering; the heightened contradictions in our case only serve to make the pattern easier to spot. (What could be a better illustration of Táíwò’s thesis than the Jewish state, which continues to mobilize the memory of the Holocaust as justification for its crimes?)

Táíwò models a different orientation in the conclusion to his essay, positing his suffering not as “a card to play in gamified social interaction or a weapon to wield in battles over prestige,” but rather “a concrete, experiential manifestation of the vulnerability that connects me to most of the people on this Earth.” Indeed, to think of pain “not as a wall, but as a bridge” is to escape from the bell jar into the world, courting a shared politics and a real solidarity.

In 1989, art historian and AIDS activist Douglas Crimp wrote “Mourning and Militancy,” an essay diagnosing what he saw as a hostility to the act of grieving among militant AIDS activists. The essay details the ways the two modes—activism and mourning—so often appear in opposition: Crimp quotes ACT UP founder Larry Kramer expressing disgust at those flocking to quietist candlelight vigils, summing up Kramer’s position with labor leader Joe Hill’s famous slogan, “Don’t mourn, organize!”

Crimp is not unsympathetic to this message. As Freud writes in “Mourning and Melancholia,” the work of real grief requires “exclusive devotion” to the task of mourning, “which leaves nothing over for other purposes or other interests.” How to undertake this momentous task of mourning, Crimp wonders, when it is constantly interrupted by more death? Or when the interruption of the grief, through action, may be the only thing preventing you from being next? “Upholding the memories of our lost friends and lovers and resolving that we ourselves shall live would seem to impose the same demand: resist! Mourning feels too much like capitulation,” he writes.

But Crimp maintains that any victory against an external enemy will be partial unless we attend to its internalized, psychic dimensions. To illustrate his point, he recalls a mobilization against a proposal for mandatory contact tracing at HIV testing sites made by then-New York City health commissioner Stephen Joseph at the 1988 International AIDS Conference. The activists opposed the proposal: Only complete anonymity would encourage people to get tested, and contact tracing was a moot point when the city couldn’t accommodate the current demand for testing, nor the subsequent need for HIV care. They demanded instead anonymous testing sites and a system of neighborhood walk-in clinics to adequately account for treatment. “We were entirely confident of the validity of our protests and demands,” Crimp writes.

But with all this secure knowledge, we forget one thing: our own ambivalence about being tested, or, if seropositive, about making difficult treatment decisions. For all the hours of floor discussion about demanding wide availability of testing and treatment, we do not always avail ourselves of them, and we seldom discuss our anxiety and indecision. Very shortly after . . . our successful mobilization against [Joseph’s] plan, Mark Harrington, a member of ACT UP’s Treatment and Data Committee, made an announcement at a Monday-night meeting: “I personally know three people in this group who recently came down with [pneumonia],” he said. “We have to realize that activism is not a prophylaxis against opportunistic infections.”

Crimp’s story dramatizes the fact that even the perfect political grievance—with the right target, the wisest strategy, the highest stakes—is compromised when the work of grief is cast aside. “By making all violence external,” Crimp writes, “we fail to confront ourselves, to acknowledge our ambivalence, to comprehend that our misery is also self-inflicted.” This appears to me to be the greatest danger of an overreliance on grievance, no matter how justified: If it is a potent means of pushing those in power, it is also effective at maintaining our investment in our own oppression.

As Jews, we are commanded to remember that we were personally slaves in Egypt. For many of us, this has been an invitation to nurse the pain of the past, to layer wound on wound until we are mostly scar tissue. But I am reminded that though the “we” of the future are commanded to remember the Exodus, those who remembered it directly were deemed unfit to enter the promised land, were killed off by the hundreds of thousands as they walked for 40 years a path that should have taken mere days. Their folly was this: When the Israelite spies returned from Canaan, they reported a land of giants. “We were like grasshoppers in our own sight, and so we were in their eyes,” they said. Soon fear and complaint spread among the former slaves that what God had promised could not be. But they were not grasshoppers. They were fierce warriors, giants in their own right, with God on their side. The trauma of their enslavement, far from providing clarity, distorted their judgment. According to midrash, God admonished them for their lack of perspective, their inability to see themselves as others did: “How do you know how I made you look to them? Perhaps you appeared to them as angels!”

To hear of people teaching each other how to give abortions or watch them flooding the streets, washing away an unjust regime, is to witness what is possible when we recognize, even briefly, that we hold power within ourselves, that we could take power—but only a capacious “we.”

Grievance by nature concedes that power lies elsewhere—and very often, it does! And yet, to hear of people teaching each other how to give abortions or watch them flooding the streets, washing away an unjust regime, is to witness what is possible when we recognize, even briefly, that we hold power within ourselves, that we could take power—but only a capacious “we.” To reach for mourning—to allow our pain to be neither repressed nor sanctified, but released—can be to trade a solipsistic victimhood for glimpses of this world-building force.

These days, I feel the threat of fascism humming in my body like a once-broken bone before the rain. It is a bequest from the pain of my grandparents, for better or worse, and perhaps from further ancestors, who fled the fanatical Spanish monarchs and priests. In living rooms and pitch meetings, as the protest or party winds down, my comrades and I debate the relative merit of one strategy over another, while conceding that none look particularly promising. But what is clear is this: We are going to need each other. This means staying attuned to the possibility of a collective power, instead of attached to a proprietary pain.

Arielle Angel is the editor-in-chief of Jewish Currents.