Best-Case Scenario

Jewish Currents interviews the authors of A Planet to Win about the radical potential of the Green New Deal.

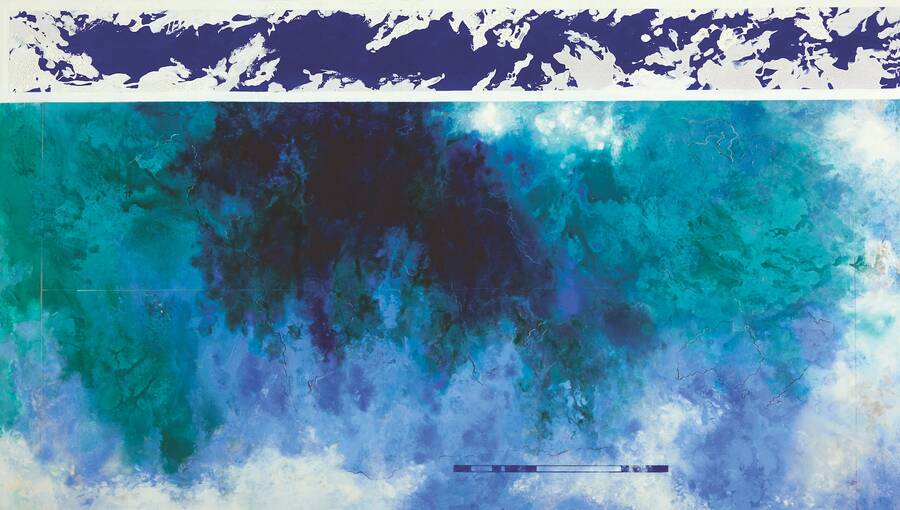

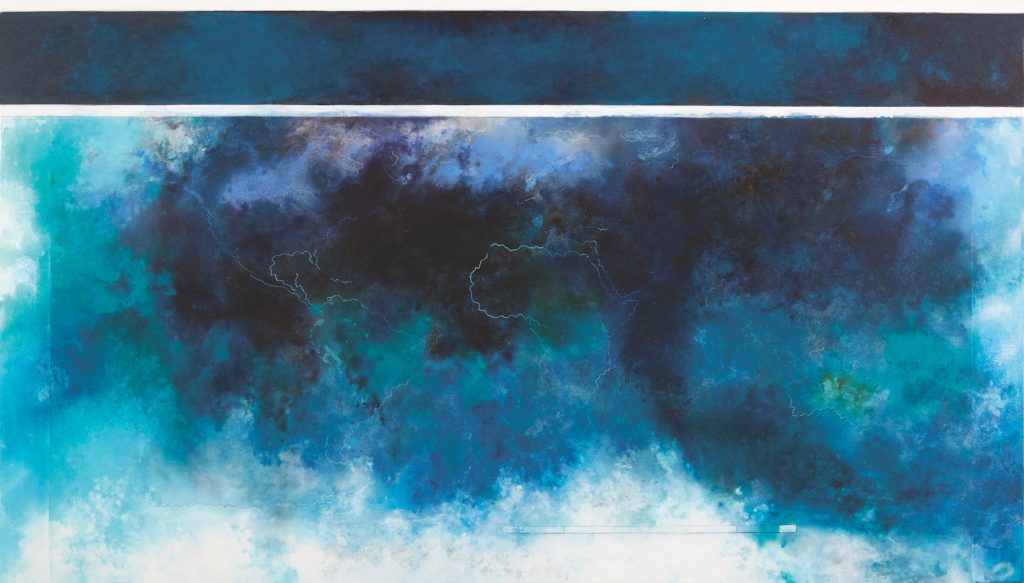

The year is 2027. Hurricanes are pummeling New Orleans. Relief workers rush in to charge the city’s emergency microgrids, and China sends a crew of experts to help repair its power system. The disaster spurs climate actions around the country. The United States is scheduled to hit net zero carbon soon—but not until 2036, six devastating years behind schedule.

A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal (Verso)—a climate politics manifesto by journalist Kate Aronoff and academics Alyssa Battistoni, Daniel Aldana Cohen, and Thea Riofrancos—opens with this glimpse of a near future in which emerging ecosocialism faces off against accelerating climate catastrophe. Jarringly utopian and dystopian at once, it is a future in which the Green New Deal, a proposal to address climate crisis and economic inequality through sweeping legislative change, has been passed—but the challenges have just begun.

As politicians vie over the meaning of the Green New Deal in the present, A Planet to Win offers a blueprint for a radical version of the proposal. What might housing look like under a Green New Deal? What about foreign policy, union contracts, or power grids? What is the best possible outcome as temperatures rise, and how can we get there? Jewish Currents editor Ari M. Brostoff and board member Alexander C. Kaufman spoke with the book’s authors about their vision for US climate politics.

Jewish Currents: You make a distinction in the book between what you call the “faux Green New Deal” and the “radical Green New Deal,” which you see as not only more just, but also more pragmatic. Why do you think it will actually work better? And what version of the Green New Deal are we seeing in the current national conversation?

Alyssa Battistoni: The Green New Deal as a phrase emerged in the Obama era, when you saw a lot of proposals that weren’t nearly on the scale of the resolution that came out this year. The proposals we describe as “faux” use language that connotes a big, ambitious, state-driven program toward a substantial transformation of social life, but are actually describing a fairly minimalist approach to addressing climate change: carbon taxes and some investments in R&D, a little infrastructure money here and there. These proposals don’t address housing or public transportation or jobs—all of the things that are part of the broader economy that produces climate change. That’s not a winner—there’s no actual political support for that kind of a Green New Deal.

We’ve been worried about the language of the Green New Deal being co-opted. This was especially a concern in the beginning, when a lot of people signed onto it; it seemed like people wanted to ride the popularity of it without committing to something ambitious. But I think the more ambitious version is actually defining the current proposal, which is a good thing.

Kate Aronoff: We think of the policy as going hand in hand with the politics. If you want to build the kind of coalition that can overcome the massive power of the fossil fuel industry or the tribal attachment of members of the Republican Party to climate denial, you need to be able to build a massive coalition. And it won't be done through backroom deals, it won’t be done through forging some sort of compromise with Mitch McConnell, which was unlikely to happen anyway. To be able to earnestly take state power and wield it effectively enough to make things happen, you need a program that’s ambitious enough to inspire people.

JC: On a practical level, how much light is there between the vision you’ve outlined in this book and the Green New Deal as it’s being sketched out by some Democrats in Congress right now?

Daniel Aldana Cohen: The book’s proposals are very much in the spirit of the radical edge of the resolution, as far as we know what that is. But the book also takes up points on which there has been a lot of silence or vagueness. One thing that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and [the climate policy think tank] New Consensus definitely have been talking about—and where we are pushing a very different idea of how it should be discussed—is the jobs guarantee.

AB: The resolution is vague about what the jobs program would look like, but in general, support for green jobs tends to focus on energy workers, construction workers—on how you move the extractive industry workers into green jobs. We’re arguing that those jobs are part of it, but we can also look at other kinds of jobs that are life-improving but not necessarily resource-intensive. People look at the Green New Deal resolution and are like, “How are healthcare and education connected to climate change?” But if we look at these areas as the kind of low-carbon, high-quality-of-life sectors we want to expand, it makes a lot more sense. That perspective actually offers a much broader view of who’s doing “green jobs” and how you can expand them.

It also offers a broader perspective on the kinds of workers who can be part of the labor coalition for the Green New Deal, rather than constantly talking about the same coal miners, who do not represent a huge number of workers in America. This isn’t to say, “Fuck the coal miners”—far from it. It’s to recognize that they’re getting fucked by the coal companies right now, and that’s probably going to get worse as there’s more pressure to get off fossil fuels, with or without a Green New Deal. So it’s like: do you want to go down with the sinking ship, or do you want a transition to jobs for all kinds of workers?

DAC: The point is that we’re trying to push forward the radical edges of what we think the Green New Deal could be. Not by being “more left than thou,” but by asking, “What does this look like concretely?”—from a perspective of maximizing the coalition, maximizing the carbon benefits, and launching a profound attack on inequality. I don't think that AOC or the New Consensus people have filled in very much on a number of these issues. The question to them should be: are they down for the logic of their own proposals?

JC: The book makes a critique of exclusively local approaches to energy transition. When individuals or communities create their own clean energy grids, you say, it’s a little like parents putting their kids in private school. Why does energy transition need to happen at a larger scale?

DAC: There’s talk in some progressive circles that seems almost libertarian—people like [climate activist] Bill McKibben say that what’s so great about solar energy is it creates a totally decentralized and autonomous local energy system. It’s striking that many leftist conversations about clean energy take for granted that we’re heading toward this completely decentralized universe. They don't understand that that requires significant overcapacity in terms of batteries, panels, and so on. Wind and sunshine are intermittent, but one or the other is usually happening somewhere; when you have a continental grid, nighttime wind from the Midwest, for example, can power New Yorkers’ ACs in the evening, after the sun has set. Bottom line: the more geography you have in the renewables grid, the more efficient your system is. So localist renewable energy means physically building way more stuff. And this stuff, especially the batteries, has huge ecological effects elsewhere. It’s made with minerals like lithium, which has to be mined almost literally out of water in sensitive ecosystems, like in the north of Chile. This can cause a lot of localized pollution, economic disruption, water shortages, and so on.

“Efficiency” often reminds us of, like, suits—oppressive technocrats. But actually, efficiency is hugely important to the energy system, because the costs of inefficiency in this country and elsewhere are going to be borne by communities on the extractive frontier.

KA: Most of the narratives we have about government action are incredibly negative. What Roosevelt’s New Deal did in its most brilliant moments was to say that a government, and a fairly big government at that, can be the facilitator for humans to experience incredible things and overcome great challenges. But we’re no longer used to thinking about the state as playing a positive role, not just in providing the things we need, but also in facilitating some of the things we want.

That’s not to say that all the action happens at the state level. But part of what was so exciting to a lot of us about the Green New Deal framework is that it reasserts a positive role for government after 40-plus years of neoliberal capture that tried to demonize the state as an actor. It recognizes that there is a crucial role for federal policy to play in climate action, for the efficiency reasons Daniel mentioned, and because otherwise, people will get left behind. Not every community is organized, not every community has the means or time to erect a solar cooperative. And what a Green New Deal can do is bridge those gaps. There are things being innovated and workshopped that come out of individual community initiatives, and I don’t want to be too hard on those. But the ultimate aim should be to see what can be scaled up at the federal level—what can be introduced, with a lot of support, to make these sorts of things accessible to many more people.

JC: You’re also skeptical of proposals that focus exclusively on creating clean energy, without attending to the entrenchment of the fossil fuel industry.

KA: An implicit part of some conversations about the Green New Deal is that we can just do the clean energy side without coming into conflict with the dirty energy. This idea is based on the assumption that if the price of solar and wind comes down enough, it will outcompete fossil fuels in a free market. But the fossil fuel industry is loaded up with trillions of dollars worth of subsidies—according to the IMF [International Monetary Fund], more than $5 trillion globally last year, if you’re counting direct and indirect subsidies. That is not a world in which clean energy has any real chance of competing.

What we say in the book is that you need to be working on both ends of the stick. We need both to bring massive amounts of clean energy onto the grid and to keep fossil fuels in the ground—as Indigenous communities who were leading the fight against the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines have long said. This means going toe-to-toe with the most powerful industry the world has ever known. There’s a narrative that everyone will win in this transition and that everyone can come on board. And I think 99% of people can come on board. But fossil fuel executives—there’s no place for them in a true transition. There’s no place for that business model to continue existing, and that needs to be clearly expressed in public policy.

DAC: If you look at the candidates, I think Inslee got it, Warren talks about it. Bernie has a truly inspiring plan with 16 trillion dollars in investments that, in my view, is the only adequate plan in terms of scope and scale. And Bernie talks explicitly in his plan about pursuing both civil and criminal lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry.

JC: This is a particularly important time to think about the nationalist side of climate policy. How does the language of patriotism and nationalism function in the current climate discourse? How can we begin to think about the Green New Deal, a national policy, as part of an internationalist project?

Thea Riofrancos: To me, some of the most disappointing policy approaches are those that frame how climate change could reboot US manufacturing in terms of competition with other countries and trying to “get our jobs back.” There are some unfortunate resonances here with xenophobic interpretations of how the economy works, tying together a revanchist national identity with a notion of economic revitalization.

The truth is, we don’t actually have all of the natural resources in the US to produce, say, electric vehicles on our own. So inevitably we’re going to need relationships between countries. The question is then, what form do those relationships take, and what is a left alternative to the “free trade” regime that can fundamentally restructure global power relations at the same time that it addresses climate change?

AB: The international dimension of climate policy has mostly just been negotiations at a very high level between elite negotiators. They’ve tried this for a couple of decades, and it hasn’t gotten very far. We’re still seeing Democratic candidates say, “I’ll re-implement the Paris Accords,” when we know that that’s the most basic step, and that the commitments made weren’t even enough to keep us below a 2 degree rise, let alone the question of living up to them.

We’re trying to think through other ways to engage; there are so many other ways that countries are connected across borders. Naomi Klein points out in This Changes Everything that global climate infrastructures and global trade infrastructures have proceeded basically in parallel for the past 30 to 40 years: on the one hand, you have the emergence of ongoing global climate talks at the UN, and on the other, you have meetings to hammer out agreements around global trade and property rights and so on through the likes of the WTO [World Trade Organization]. But these two parallel sets of institutions are rarely discussed in relation to one another. Unfortunately, the climate negotiations have been pretty ineffective—the real action is happening at the level of global trade negotiations. And so we’re saying, “Let's go where the action is.”

TR: Let’s say, for example, that other countries want to purchase green technology made with US government investment, but the US puts a policy into effect that this technology must be manufactured in the US. That would be devastating to Global South countries that have more limited resources, and are also not the culprits of historic emissions. So it’s important to use our trade policies to revitalize manufacturing and create other sorts of jobs in the US, while simultaneously raising environmental and labor standards around the world, and ensuring that clean tech goes where it needs to go—to tie our policies to these labor and environmental standards, rather than viewing them as things that are tacked on and never enforced.

We also talk a lot in the book about what types of social power would need to be articulated in order to press governments to move in the right direction. It’s exciting to think about how workers and communities that are situated across these globally dispersed supply chains—Indigenous communities in South America at the site of extraction, and workers assembling the technology in the US or China, for example—might enter into forms of solidarity with one another. They might be experiencing similar types of labor violations, for example. We need to start looking at these relationships of productive activity as an opportunity—to recognize that forms of worker and community leverage and solidarity can cross national boundaries in the same way that capital and climate do.

JC: There have been a few critiques of the Green New Deal from the left, like Jasper Bernes’s piece in Commune, “Between the Devil and the Green New Deal,” which argued that a Green New Deal is essentially a reformist fantasy, an impossible attempt to reconcile decarbonization and continued economic growth. What do you see as more or less valuable in these critiques?

TR: One thing I’ve found frustrating about—not left critiques, but whole-cloth rejections of the Green New Deal from the left—is that they kind of simultaneously say it’s too radical to happen, and that it’s not radical enough to make a difference. And I find that that leaves interlocutors in a bind, because either of those arguments could be potentially compelling, but both of them at once don’t feel like an invitation to an actual discussion of how to move forward.

I just got back from the DSA [Democratic Socialists of America] convention, and one of the things that many of my comrades and I had been working for was a resolution—which was nearly unanimously adopted—to have the organization orient to the Green New Deal as a terrain of class conflict and popular mobilization that is still relatively open and undefined. That means that this is an arena where the left can be forceful protagonists in defining what the content of the Green New Deal is, and how we want to see it implemented. I was really happy to see that as a point of unity in DSA; I think it’s a barometer of where the broader left is at right now.

So, for the radical left—environmental justice movements, Indigenous justice movements, labor movements that are more militant in their orientation—I think the most fruitful way to engage with the Green New Deal is to see it as something that the left, in all of its instantiations, should be attempting to define, but also as something that requires grassroots mobilization in order to make it a reality.

DAC: Can I say something as a Jew? I think that many of us in the Jewish community grew up learning stories where a group of farsighted people say that there is a catastrophe coming and we have to do something. And in those stories, there’s always a bunch of very serious people that you could call the centrists, or establishment figures, or elitists, who say, “Don’t worry about it, we’re taking care of it, everything is going to be fine.” And it’s not. This is very much how I read the Holocaust, with so many people—Jewish and non-Jewish—downplaying the threats all the way through the 1930s. I know there are differences, but at the level of the parable, the moral precedent, I see this moment as echoing a long history.

The flip side is that we’re still here. We should have done way more a long time ago. We didn’t. But it’s not too late. And so I don’t think the optimism of our book is this Pollyannaish view—“We just flicked the Green New Deal switch and now everything is great”—but rather that, in the face of the most existential threat we have known, we can and must still build a better world. After all the things you learn as a child in our tradition, complacency just is not an acceptable way to be a grown-up in the face of looming violence.

KA: There’s a lot of writing—by male novelists, for instance—that looks romantically at the end of the world as something to ruminate on and use as an excuse for your own self-realization, and I think that’s antithetical to the tradition Daniel was just talking about. If you actually have the prospect of annihilation in mind, then the task at hand must be to actively work against it.

That’s reflected in the reality of the climate crisis. Every tenth of a degree of warming translates into tens of thousands of deaths. There are very real human costs to delaying action, and there’s never a point at which it’s over. It can always get worse. Which means there’s always a case to be made for doing more, and there’s never a case for resignation.