An Archive of the Present

A conversation with scholar Gil Z. Hochberg about the limits and potential of the archive

Scholars, writers, and artists have long looked to the archive as a site of boundless possibility—a mechanism for recovering suppressed or erased histories to elucidate the past and inform the present. But in recent decades, theorists have questioned this attachment and its place in radical and decolonial movements, arguing that it often amounts to a reification of official state narratives.

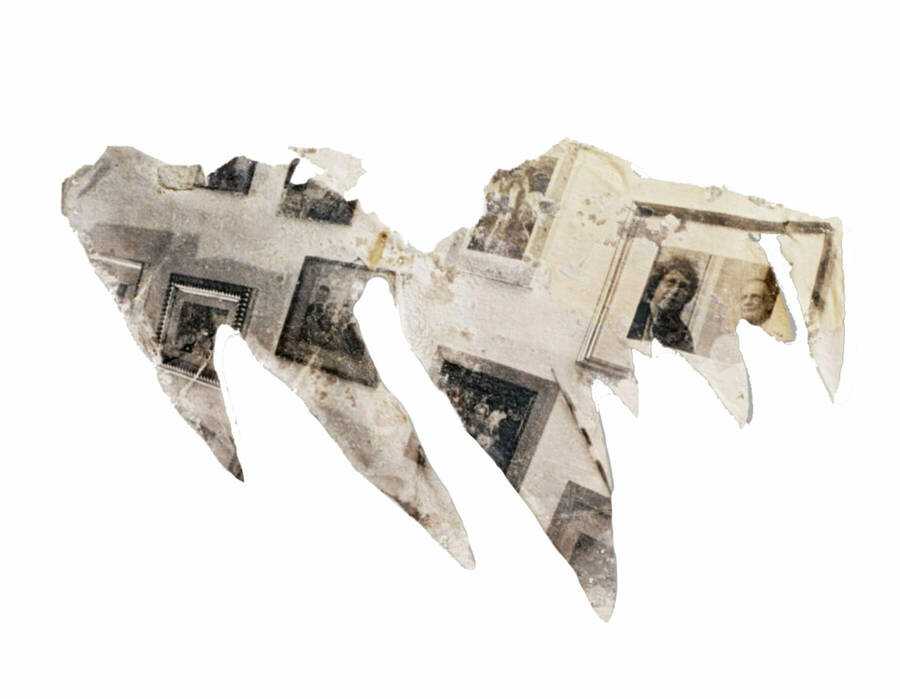

In her recent book Becoming Palestine: Toward an Archival Imagination of the Future, scholar Gil Z. Hochberg intervenes in this debate by examining how the work of contemporary Palestinian artists challenges prevailing notions of what constitutes an “archive” to deliver a vision of radical future-making. Analyzing eclectic pieces by filmmakers Jumana Manna, Kamal Aljafari, and Larissa Sansour; choreographer Farah Saleh; and visual artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, the book asks us to practice what Hochberg dubs a “future-oriented archival imagination”—one that sees the present itself as an archival moment in the making.

I spoke with Hochberg about the political limits and potential of various conceptions of the archive for Palestinians and other colonized peoples. Our conversation has been condensed and edited. It originally appeared yesterday in the Jewish Currents email newsletter, to which you can subscribe here.

Hazem Fahmy: In the book, you question the pervasive scholarly obsession with the archive as a site of emancipation in and of itself, what Jacques Derrida called “archive fever.” What do you see as the problem with that preoccupation?

Gil Z. Hochberg: I want to critique a certain kind of reliance on the archive as a source of knowledge. But it’s important to me that we don’t throw the baby out with the basket. I am not suggesting that archives are not important—quite the contrary. What I am arguing in the book is that it’s very important to separate the archive and archival thinking from a [linear] temporality—past, present, future—and from the idea of the revelation of the past informing the present and leading to a more just, more correct future.

So my beef, so to speak, with “archive fever” is really about what it does to the present. The past is very attractive. There’s this idea that you will dig, dig, dig, and you will find the first bones of a dinosaur, and then you build it up the right way, and you’ll have discovered the past—and therefore will better understand the present. I am suggesting that this eagerness needs to be redirected to the present. The present actually merits the attention of an archive.

HF: How does attachment to archives relate to the privileging of written evidence over other kinds—such as oral histories maintained by colonized peoples—and of colonizers’ narratives?

GZH: The archive is often treated as if it serves as a gate into what really happened. If as a scholar you’re really, really lucky, you might find that one document, that one signature, that one description, that proves something beyond all doubt. But the question is: Prove to whom, and in what sense? When is it that we can “prove” that the Americas were colonized? What does it mean to “prove” that what Indigenous people are saying is indeed “true”? The written remains a force that no oral tradition can ever overcome. The heard remains hearsay, while the written is a universal document. It’s as if the knowledge of colonized people needs to be validated by some global court. It’s almost perverse! You actually have to find the perpetrator’s documents, and the more documents you uncover, the more reliable the story becomes. It’s like in a trial where there is a rape victim, but unless we find the rapist writing, “Dear journal, yesterday I raped so and so,” it didn’t happen.

In the case of Palestine, in the late 1980s, there was a moment when [Israeli historians] Ilan Pappé and Benny Morris and a few others came out with official documents that “proved” the events of the Nakba [the Arabic name for the events of 1948, when Israeli forces expelled an estimated 700,000 Palestinians from their homes]. There was this moment of elation, this sense of, “Okay. Here is the official account. The State of Israel’s narrative has now crumbled.” I’m not saying that was of no significance. But as time passes, and those sorts of documents are just circulating time and time again . . . they’re not secrets. When they’re revisited over and over and over again, that actually establishes a certain narrative of mastery—not only of the past, but also of the archive itself: These are the voices we have to go back to, in order to prove that things happened, and how they happened.

We keep returning to state archives—and the vast majority of archives, 90% if not more, are state archives—that have now switched from denial to openness, saying, “We have nothing to hide.” This actually happens in many contexts. Time and time again, when there are atrocities and genocide, the first reaction is to hide. And then when things are open, it’s to saturate with confessions.

HF: And the idea that the availability of the information means things will change betrays a profound misunderstanding of how historical knowledge affects the present. If you look at a context like the United States, for example, no serious person would deny that it has a history of genocide and chattel slavery. The fact that these things happened isn’t in question. But as for the implications for the present—how to deal with those legacies and repair their harm—that’s a whole different story. So if more documents were to surface now that more accurately account for certain American atrocities, that wouldn’t change those attitudes.

GZH: I see that in many contexts. In the 2000s, Europe went through some kind of an epiphany. Countries that were less often recognized as evil colonial forces, like the Dutch, started to do this cleansing thing, where they found all these archives and proved that they had slaves. Now, I’m sure a lot of Dutch people had never thought about their colonial legacy, and now they know. But that cannot be a goal in and of itself.

HF: One of the central arguments of your previous book, Visual Occupations, is that “the Israeli occupation of Palestine is driven by the unequal access to visual rights, or the right to control what can be seen, how, and from which position.” Where do you see access to the archives fitting into that analysis?

GZH: The easiest thing to do to manipulate people’s minds is to change what they see. The visual politics of radical partition is what holds everything together. It’s not just having walls, and having people living in different conditions, but it’s also making sure that those people don’t see each other, and that they don’t see the same thing. As I mentioned in that book, the wall looks very different on both sides. On the Israeli side, it looks very small, almost like just a cute fence, because it’s built in such a way that there’s grass and trees all over. And then the visual we all know—of the cement—is on the other side.

In terms of the archives, of course people find ways. Those are the borders that can actually be crossed simply in the sense that individuals can copy and circulate materials for others. So within the framework of divisions and partitions, especially today—with the ability of transferring things digitally—it’s sort of a minor concern. But what’s amazing about many of the artworks in the book is that these younger Palestinian artists have realized that they don’t need the Israeli state archives. They have archives. First of all, the stones and the buildings and the flowers are archives. And also, there are unwritten archival materials. The Israeli state archives, and the not-quite-solid archives of the Palestinian Authority, are not the only options.

HF: Some of the media theorists you cite, like Jaime Baron and Laura Marks, argue that the obsession with the archive, particularly in the realm of the visual, is in a way indistinguishable from a sense of longing for the past. Where do you see the kind of “future-oriented archives” that you’ve analyzed fitting into that?

GZH: My problem isn’t with nostalgia, per se. We all experience nostalgia. But it’s not a particularly future-oriented feeling. It has to keep you in some kind of a state of longing for something that has been better, that you have lost, because the pleasure of nostalgia is in feeling that though you lost the object, you can reclaim it in mourning. There’s no problem with that, but it’s not a recipe for moving forward. I think we need to focus on—and this is something I took from [English scholar] Stephen Best—the question of what this “we” is that we’re trying to revive, and whose story we are trying to tell. The collective that comes together in generating archives is a collective that is building itself.

HF: In the book, you engage with an eclectic range of artworks, spanning very different mediums and sensibilities, from Kamal Aljafari’s Yaffa Trilogy and its haunting use of footage from Israeli films to comment on the colonization of the city, to Farah Saleh’s recreation of scenes of resistance to an attempted ban on Palestinian higher education during the First Intifada. What was your process for selecting these works?

GZH: I only engage with works that I’m mesmerized by, that touch me to the core, that make me think and feel. I did not come to the project with an argument—when I say in the book that the artists are as much the writers as I am, I really mean it.

I believe that art thinks, and it thinks in ways that argumentative, analytical thought cannot. To me, these particular artworks have made me think in ways that no texts can. They reshaped the way I see things. There’s a kind of potentiality in them—an approach to the past that relies on archives, but is not set on proving anything, and is actually recreating an archive of the present. It’s not just about going in and finding the folder in the archive. That’s just the beginning. What are you going to do with it?

Due to an editing error, a previous version of this conversation described Stephen Best as a philosopher. In fact, he is an English scholar.

Hazem Fahmy is a writer and critic from Cairo. His work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Mubi Notebook, Reverse Shot, Boston Review, and Prairie Schooner.