Hersh Dovid Nomberg (1876–1927) was a writer, essayist, and political activist born into a Hasidic household in Mszczonów, near Warsaw. As a young man, Nomberg began dabbling in forbidden secular texts, particularly Russian and German literature, which provoked a crisis of faith. Nomberg’s newfound atheism and growing literary ambitions led him to leave his wife and infant sons and move to Warsaw, where he became a protegé of I.L. Peretz. Around 1900, he began publishing poems and short stories in both Yiddish and Hebrew, and came to be considered one of the most influential Yiddish writers of his generation.

Having penned dozens of successful short stories, he shifted his focus toward journalism and politics following the First World War. He was one of the founders of the Folkspartei, a political party dedicated to safeguarding secular Jewish cultural autonomy within the Polish Republic. As a representative of the party, Nomberg served in the Sejm (Polish parliament) from 1919–1920. Though based in Warsaw, Nomberg never stayed in any one place for long. He traveled extensively throughout Western Europe, South America, Russia, and Palestine. He died at the age of 51, having suffered from chronic lung problems for most of his life.

“Am I a Jew or a Pole?” (“Bin ikh a yid tsi a polyak?”) was first published in 1911 in Warsaw’s Yiddish language daily Haynt. It’s one of several short sketches where the narrator, a thinly-veiled stand-in for the author himself, sympathetically observes the fellow Eastern European Jews he meets along his travels in Western Europe.

A BOARDINGHOUSE is like a train carriage. You arrive, someone else leaves, you have a little chat in the meantime, acquaintanceships are made that last several days, and no one has any interest in who you are or what you do.

It is the life of a butterfly. Easy and ephemeral, leaving behind it not a trace of a lasting impression.

But little Staszek had more luck than most, by which I mean many of the other guests, having long returned to their homes, still remember him to this day. I have not forgotten him either.

A sturdy, tanned boy of about six or seven, with the dark, piercing, occasionally somewhat startled eyes typical of his race. He was invariably dressed in a light swimming costume, his bare arms and legs burned from the sun, and he was always occupied, always amused. A little inventor of new games. Out in the fresh air he was fidgety, but at the dinner table he was the calmest child you’ve ever seen. He sat there, eating and speaking in every respect like a grown-up, if a little more slowly. In such adult company he did not feel at home—but not to worry! He was a child with healthy nerves, and good sense; he could get through it.

The other guests were fond of him, always beaming. He was the first one they’d greet in the morning, and from all sides he was the recipient of warm sympathies. It was on account of him too that one sought the acquaintance of his parents, a young couple from Galicia.

The father was a young lawyer, his mother a young, beautiful, brown-haired lady. A Jewish couple, assimilated, of course.

I was the only one who recognized them as Jews, but I said nothing of it. A boardinghouse is no place for debates on the wretched “Jewish question.” They had come here to rest after all.

But I felt sorry for the boy, a potential little convert to Christianity. Would that he could cast off that which is ugly and weak of our race! Alas, that is not how it goes.

Little Staszek conquered worlds. He had accompanied his parents to climb a mountain that many adults cannot manage on foot, and he returned from the difficult trek, strong and refreshed. At dinner, the owner of the boardinghouse gave him flowers, and the other guests did not leave him in peace for even a moment. He was the hero of the boardinghouse—a miniature hero.

I GOT TO KNOW THE FAMILY over the course of several days, walking together in the mountains surrounded by snow and ice. That giant, Nature, has the power to open people’s hearts. By the noise of the waterfalls, the young husband was not shy to tell me all, even about his Jewishness.

His father was a wealthy, respected man who ran a Jewish home. Two of his brothers had converted to Christianity, while the other was a Zionist. For Passover they all come together for the seder, even the converts. They found no solace in the lap of their new faith. Their mother silently wipes the tears from her eyes when she sees them, while their father acts as if nothing has changed, and together they celebrate the seder.

The young lady, on the other hand, grew up in an assimilated home, raised in the Polish culture. In her father’s house they dismissed the seder with open scorn. For her, Jewishness means peyes and shtreymeland the Sadigure Hasidim, and she hated it. An unapologetic Jewish antisemite.

I allowed myself the indiscretions of asking the young lady if Staszek, our little hero, took part in her in-laws’ seder celebrations.

It turns out that very question had caused the young couple no end of sleepless nights.

The mother does not want her son to have deep-seated impressions of a Jewish childhood, because that, she asserted, would cause him trouble in life. She has no desire to raise a broken Goy, like her brothers-in-law, the converts, who are uneasy when Passover comes around, feeling drawn back to the seder and to home. She wants to raise a proper Goy, pure and simple, without complications. Let him know nothing of Passover, and later he will have no nostalgia for it. She wanted to prepare little Staszek for his career as a convert. As far as she was concerned the best thing for him would be to have him baptized without delay, but her husband was himself a broken, nostalgic Jew who runs home every Passover. What can you do with him?

In the end they did not bring Staszek with them for Passover; they left him at home with the maid.

Neither parent was satisfied: a child must have some sort of childhood impressions that will stay with him, some kind of religious ceremonies, a little festivity, a holiday spirit, and Staszek lacked these things. They understood this, but let’s be honest: the child’s mother had the more pragmatic idea.

But the young lawyer had two converts and a Zionist for brothers who did not feel remotely comfortable with the new situation, and he himself voted for a Socialist during the last elections in order to ease his Jewish conscience.

Quietly, he whispered in my ear, “Assimilation has gone bankrupt.”

That is to say, he himself had gone bankrupt, but that was something he did not seem to recognize.

Incidentally, he was a busy man. He does not have a high opinion of the political speechmakers, neither the Zionists nor the assimilationists. There is too much corruption in Galicia; the Poles are antisemites, so he voted for a Socialist, though by nature he was afraid of the Socialists.

That’s how little Staszek is growing up, a fresh, sturdy sapling unaware that over his innocent head hovers the Jewish question in all its sharpness.

Yet perhaps he does know? Children think much more earnestly than we give them credit for. They do not listen when we chatter, when we are not speaking from the heart. But to an earnest discussion they prick up their ears, and their eyes twinkle then with curiosity.

One time, as we were walking together uphill, we spoke about Jews. Staszek usually overtook us with his little legs. But this time he walked along beside us, and it did not occur to us that he was listening to our conversation. Suddenly he drew close to his father, took him by the hand, and blurted out a question:

“Powiedz mnie, Tatusiu, ja jestem Polak czy ‘Żyd’?” (“Tell me, father, am I a Pole or a Jew?”)

“What a question!” The young man glanced at his wife, while I watched them both. Staszek however demanded an answer; he wanted to know. It was a question concerning his life and he did not know the answer.

“Niech mi tatuś powie.” (“Tell me, father.”)

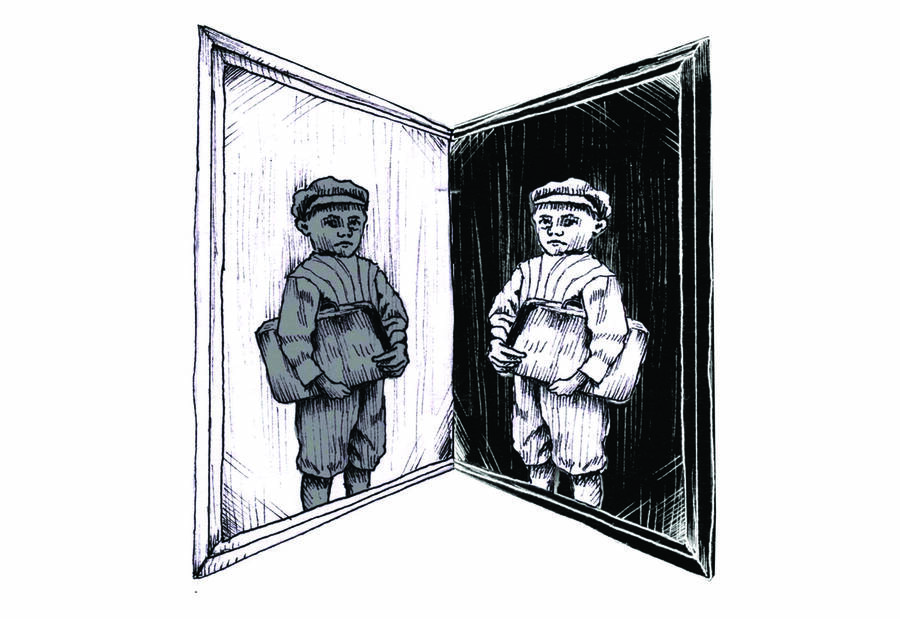

His father found himself in an awkward position. It’s quite possible that, had I not been there, he would have simply answered, “a Pole,” but for my benefit he responded, “Ty jesteś Żyd-Polak.” (“You’re a Jew-Pole.”)

Staszek, however, did not understand the answer. It was as though he had been told: “cold-hot” or “black-white” . . . He knew there were two categories of people: one a respectable, noble group and a second, disrespectable, lowly group to which it was shameful to belong. He had been raised with such notions, and his real question had been: am I unfortunate, or fortunate? Will things go well or badly for me? You’re unfortunate-fortunate, things are good-bad, you are a Jew-Pole . . . a child’s mind is not yet corrupted enough to understand such things.

He protested, demanded an answer.

“Tell me the truth, father . . .”

His mother answered in a harsh, angry voice:

“Ty jesteś Polak.” (“You are a Pole.”) Staszek’s questions stopped. He followed us silently, lost in his thoughts.

But he was not satisfied.

That night, just as we returned from our mountain trek, and were strolling outside, I noticed Staszek walking very close beside me; he wanted to catch me alone. I walked away to the side, and Staszek was soon beside me again. He asked me quietly, secretly:

“Niech mi pan powie naprawdę, ja jestem Żyd czy Polak?” (“Tell me honestly: am I a Jew or a Pole?”)

Poor child! I didn’t have the heart to tell him the truth, that his parents had lied to him. I lifted him up in my arms and kissed his forehead.

“Niech mi pan powie . . .” he asked again.

“You’re a good, clever child,” I told him, “and when you’re old enough, you’ll see for yourself . . . ”

And he left me, angry and unsatisfied. His last opportunity of getting a straight answer had failed him.

He did not play games that evening.

The Jewish question went with him to his bed.

Hersh Dovid Nomberg (1876–1927) was a Yiddish and Hebrew short story writer, journalist, and editor. He was a central figure in Warsaw’s literary scene.

Daniel Kennedy is a France-based translator and a translation editor at In Geveb: A Journal of Yiddish Studies. His translation of Warsaw Stories by Hersh Dovid Nomberg will be published this year by the Yiddish Book Center.