The author at the site of her crash

Photography by Liz SandersAfter the Hit-and-Run

Can restorative justice offer crash victims like me—and the drivers who harmed us—the healing we need?

I didn’t particularly want to go for a run on the evening of Saturday, August 28th, 2021. But I’d spent the day lying around, recovering from an exhausting weeklong work retreat and a late night hanging out with colleagues, and I hoped a run might bring me back to life. I remember that I wore a new pair of running shorts, a special flower-printed Nike edition, because I felt a slight pang when an ER resident later had to cut them away from my body.

Throughout the previous week it had been too hot to think, up in the low 90s, but the temperature had mercifully plunged back to the 70s. I allowed myself to take the shorter version of my route to Fort Greene Park, forgoing the idyllic path through Clinton Hill in favor of the arterial Fulton Street. Fulton Street is not pretty, but I like how it crams the maximum amount of life into the minimum number of square feet, with its bodegas, beauty supply shops, yuppie bars, liquor stores, and a mosque where men pray on mats out front.

I made it to the park and headed back the way I’d come on Fulton. Soon enough, I was a few blocks from home. The light changed; I ran off the curb and onto the crosswalk. As I remember it, I heard the shouts before I felt the impact: Someone yelled “hey!” and a bright blue van hit my right side. Then I was trying to get up, and many people were yelling and approaching me. “Come back! You hit someone!” a man screamed at the van, but the van was not listening, the van was no longer there. I kept saying “oh my god.” I made it to my knees and then decided to lie back down. Someone was bringing me my phone and headphones. Strangers had formed a half circle around me, blocking off the street. A woman introduced herself as a trained EMT. “Did anyone see what happened? Was the light red? Was it my fault?” I asked. “You’re a pedestrian, it’s never your fault,” said the woman, who wanted me to keep my neck very still. I wasn’t sure I believed her. I knew my name, I could move my fingers, I could move my toes. The pain was all down my right side, but also it was everything, and when I breathed, the bottom of my breath seemed to land on the edge of a knife.

I heard the shouts before I felt the impact.

As the ambulance arrived, I was thinking about whether I could still somehow make this thing, which was not supposed to have happened, un-happen. I had been so close to deciding not to go for a run in the first place; the alternate reality where I was still resting safely on my couch seemed to hover within reach. When the EMTs deposited me into the back of the ambulance, I noticed I was only wearing one of my shoes, the other one washed away forever in the tides of Fulton Street.

When the van hit my right side, it broke seven ribs and my clavicle and collapsed my lung. Had I been hit slightly higher, I could’ve had brain damage; slightly lower, and the crash could’ve permanently impacted my ability to walk. Instead, with time, the lung sprang back to form, and the bones found each other again, without much fanfare or prodding. The entire affair resulted in the greatest show of community care I’ve ever experienced. Complete strangers comforted me and took pictures of the license plate as the van sped away; my mom dropped everything and flew in to stay by my side for two weeks; my best friend packed my things and brought them to the hospital. For weeks, as my right arm hung limp in its sling and I maneuvered in and out of bed sideways to avoid aggravating the pain in my ribs, friends showed up at my door with home-cooked meals and groceries. Experiencing such kindness from people who acted out of an instinctual desire to help rather than any obligation was life-affirming, invigorating.

Yet this was all set in motion by a radically antisocial act: Someone sped through a red light, plowed into me, and then drove away. It was due only to luck, and not to care, that he didn’t kill me. Our fates were bound by the simple fact of occupying the same street at the same time, but from the moment he fled north from the intersection, we were to communicate solely through a bureaucratic game of telephone: The van was owned by a small business whose owner worked with the insurance company representatives, who worked with my lawyer, who worked with me. The driver who had caused the harm was shrouded, unknowable—so absent from what happened next that I sometimes came close to forgetting about him entirely. The bones broke; the bones regrew.

In 2021, I was one of 7,203 pedestrians injured by a car in New York City; an additional 127 pedestrians died that year, while 4,619 cyclists were injured and 19 killed. (The numbers were similar—and, in some cases, worse—in 2022.) Seven years earlier, New York City had adopted the Vision Zero framework, agreeing to enact reforms based on a model from Sweden that aims to eliminate deaths from traffic crashes. Experts argue that system-wide transformations are the best way to vastly reduce traffic casualties: We could design roads to make it harder for drivers to speed and easier for them to see pedestrians; we could also regulate the manufacture of big cars like SUVs (which decrease visibility) or force the automobile industry to design cars that can’t go over a certain speed limit. But the political will to bring about such changes is often lacking. At first, New York City proved itself a leader in pursuing Vision Zero objectives, and its traffic planning changes—reducing speed limits, giving pedestrians a head start at traffic signals, installing protected bike lanes and raised crosswalks—caused fatalities and injuries to decline. But by 2019, numbers had begun to creep back up, and activists accused the mayor of caving to political pressure from drivers, stalling reforms. The arrival of Covid-19 further sidelined the city’s goals, delaying street improvement projects, while a larger breakdown in social norms caused a surge in reckless driving. These trends have plagued communities nationwide: In 2022, more than 7,500 pedestrians were killed in the country, a four-decade high. In general, the United States has long lagged behind other wealthy nations in ensuring safety on the streets.

Along with lobbying for safer road design, pedestrian and cyclist advocates have often responded to the lethal status quo by pushing to increase criminal penalties for traffic offenses. They point out that hitting a pedestrian or cyclist is usually only a low-level misdemeanor if it is considered a crime at all, and the police often let even the gravest incidents go uninvestigated—meaning that victims of traffic violence, in addition to feeling that they have been deprived of justice, generally lack access to the courts’ victim services programs, which can cover funerals, therapy, and lost wages. Officers “will tell you that they didn’t become a cop to do traffic law enforcement. They’re out there to ‘catch bad guys,’” Steve Vaccaro, a local cyclist and pedestrian advocacy lawyer who represented me after my crash, told me. Among safe streets advocates, it’s a popular adage that “the easiest way to murder someone and get away with it is to do it with a car.” In 2014, the New York City safe streets advocacy group Transportation Alternatives supported a push to make hitting a pedestrian or cyclist who has the right of way—then not a crime in its own right—into a misdemeanor, arguing that the threat of even minor criminal consequences would make drivers more conscientious on the roads; the law passed, though police rarely enforce it. Analogous organizations have supported similar legislation in communities around the country.

In recent years, however, advocacy groups have begun to reconsider their call for carceral and police-centric approaches. Influenced by the Black Lives Matter movement, which has drawn attention to the way traffic stops act as sites of police violence, and by the uprisings of 2020, which pushed arguments for police and prison abolition into the mainstream, safe streets activists have increasingly acknowledged policing’s heavy toll on Black and brown drivers. Many now note that communities of color are disproportionately burdened even by relatively modest proposals, like increasing fines for traffic violations—and that traffic stops are among the situations in which Americans are most likely to encounter the police, meaning that scaling back police involvement in daily life will require lessening their role in traffic safety. The past decade’s critiques of the carceral system have also drawn new attention to sociological studies showing that harsher punishments—such as longer sentences—do not deter people from committing crimes.

Lately, instead of emphasizing the importance of criminal consequences, advocates have begun calling for drivers who hit pedestrians or cyclists to be held accountable through “restorative justice,” a term for an increasingly popular set of practices that eschews a focus on punishment in favor of an emphasis on repair and an effort to meet victims’ needs. In 2020, for example, Chicago’s Active Transportation Alliance wrote in an issue brief that its members “believe in restorative justice and that the goal of enforcement should be to address and prevent harm, not unduly punish people.” This past February, after Memphis police fatally injured a Black man named Tyre Nichols during a traffic stop, Transportation Alternatives—the group that had advocated for the 2014 law in New York City—published a statement titled “The Urgent Need to Remove Police from Traffic Enforcement.” The group noted that it had recently helped launch a new program called Circles for Safe Streets, which was trying to use restorative justice to address the harms of traffic violence.

I became interested in these tensions within the traffic safety movement in the months after I was hit. I had realized that I didn’t know what I thought should happen to the driver, whom I will refer to as R. It’s anathema in street safety circles to call a crash an “accident,” since advocates and victims believe the term elides both the structural conditions that make crashes more likely and the responsibility of the drivers who cause them. But habits are hard to break: In conducting interviews for this piece, I frequently found myself saying “my accident” before quickly backtracking: “I mean, my crash.” It does seem to matter that the drivers who cause great harm, while they may be careless, are not setting out to injure or kill someone. In cases like mine, the decision to flee the scene adds an element of cruelty, but I could imagine legitimate—if not exculpatory—reasons why someone might do so. What if they were unable to afford a ticket or legal fees? Undocumented and wary of immigration consequences?

When I returned to work a few weeks after the crash, one of my first projects was a collaboration with a young man who had just spent a week on Rikers Island—New York City’s largest jail—during an acute understaffing crisis. He described a nightmarish scene: jam-packed cells, no showers, insufficient food, people in medical distress left to suffer on the floor. I knew I didn’t believe that R. deserved such treatment, or that experiencing such conditions would make him less likely to harm someone else with a car in the future. Why, as the abolitionist geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore has asked, would we expect the violence of incarceration to combat the violence of our society?

I was glad, therefore, when the police abandoned the case without charging R. I had wrangled a personal injury settlement and full coverage of my medical bills from the vehicle’s insurance company, which helped me more than any punishment for R. would have. Still, I struggled with the knowledge that he would not be held directly accountable. When friends and family asked if the driver who hit me would face any consequences, I said no, and that it was for the best. But I knew it wasn’t that simple. Would I have felt satisfied with the insurance settlement if my injuries or trauma had been more severe? What if it had been someone I loved who was hit, and I had been the person at the bedside, watching? And what if R. went on to hurt someone else?

After the crash, I wanted to believe another world was possible, but I still found it hard to envision, concretely, what a just response to R.’s actions might look like—or what I might want from him to help me heal.

Prison abolitionists often speak of violence as a social problem, born of systemic factors, like poverty and disenfranchisement. They argue that our response to it also reflects a social deficit: Our reliance on locking away harm-doers is the flip side of our failure to consider the context for their actions, and the conditions that would enable them to change their behavior and make amends—factors we must confront if we’re ever to move toward a world without prisons. In a forthcoming conversation on abolition in the Radical History Review, the organizer and law professor Dean Spade argues that “the existing criminal punishment system . . . wants us to be as passive as possible and not solve our own problems with each other.” This, he said, is why envisioning a prison-free world is “hard for a lot of people who are new to the analysis . . . It’s a tall order to actually know our neighbors, to care about each other, to get better at having hard conversations.” Though I don’t necessarily consider myself “new” to the analysis—I first began reading the work of abolitionists almost a decade ago—I recognize myself at least partially in Spade’s description. After the crash, I wanted to believe another world was possible, but I still found it hard to envision, concretely, what a just response to R.’s actions might look like—or what I might want from him to help me heal.

A year and a half after my crash, I started speaking to the people who had built and participated in Circles for Safe Streets, the new restorative justice program for traffic violence in New York City, to learn about its efforts to address serious crashes without resorting to incarceration. Meanwhile, I went looking for the man who hit me. I wanted to know why he did what he did, so I might more easily understand his actions in a social context, rather than as one person’s irreparable cruelty. I wanted to ask him why he drove away.

On a Friday morning in November 2016, Ron Filepp decided to go for a bike ride. His wife, Robin Middleman Filepp, his partner of nearly 40 years, kissed him goodbye before he left their home in central New Jersey, where Ron—a former radio DJ who now worked as a court clerk—had built a studio for Robin, an artist, in a backyard that abutted the woods. Ron, who was 64, was an avid cycler. This sometimes worried Robin, who wished he would ride on trails, away from cars. That day, he planned to drive 45 minutes to a rural road in a forested area called the Pine Barrens. He told her not to worry if he was late getting back.

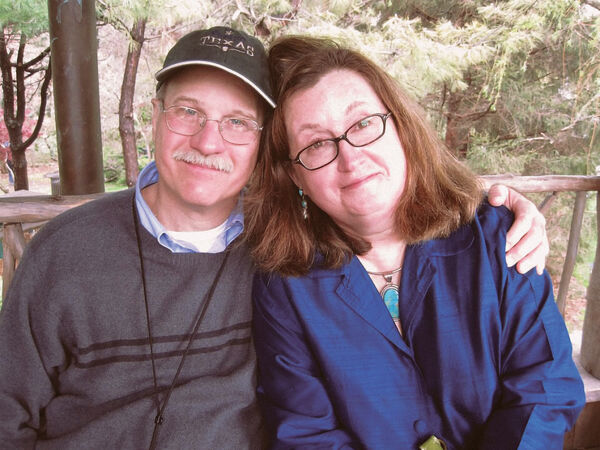

Robin Middleman Filepp in Brooklyn

All the same, around 6:00 pm, Robin began to think it was strange that Ron wasn’t home yet. She knew better than to panic when he didn’t pick up the phone, since Ron was “infamous” for losing his phone in silly ways: “One time, after I couldn’t reach him, he said, ‘Oh, I dropped my phone in the stream,’” Robin, who is 71 and has neat gray hair and wears bright green hexagonal glasses, told me recently over coffee. Robin speaks gently and deliberately, sometimes looking briefly into the distance while she gathers her thoughts. That November night, when 7:30 pm rolled around with no sign of Ron, she began looking for reports of accidents online. She told herself that if he hadn’t returned by 8:00 pm, she would call the police. But she didn’t have to. Right on the hour, two state troopers showed up at her door, bringing the news that, at 3:30 pm that day, Ron had been hit by a car and killed. The driver had fled the scene. The 911 call came from a woman who had seen his crumpled bike on the side of the road, which she took for a pile of sticks until she noticed Ron lying there and pulled over. Robin would eventually find out that Ron had died almost immediately upon impact, which came as a kind of relief. She had feared that he had been left “lying there suffering while people went by.”

The woman who hit Ron was only 20 years old. Eight months later, after pleading guilty to leaving the scene of a fatal accident, she was sentenced to a year in jail—of which she served six months—and four years of probation, as well as two years of license suspension. Attending hearings leading up to the sentencing, Robin was frustrated that the woman didn’t seem to show remorse. “More than anything, I was looking for an apology. I was looking for recognition and an acknowledgment that she took a life,” she said. Instead, she thought the woman’s manner in court seemed glib, lacking in depth. “The whole time she just looked straight ahead. And she was crying. And I had a gut reaction to it,” Robin said. “I wasn’t seeing anything that [expressed] compassion for me or for Ron’s memory.” This impression stemmed in part from the circumstances of the crash: Robin said she was told by the county prosecutor that the driver never called the authorities, but sent a series of text messages to her mother and a friend, first saying “I think I hit a deer,” and then, “I think I hit a person. I’m fucked, I’m going to jail.” According to the prosecutor, it was the woman’s mother who called the police. To Robin, this reaction suggested that the driver knew she had hit someone, but was more afraid for herself than for the victim of the crash.

Robin was frustrated that the woman who hit Ron didn’t seem to show remorse. “More than anything, I was looking for an apology,” she said.

In the year and a half after Ron’s death, Robin struggled, attempting to end her own life three times by overdosing on prescription drugs. After waking up the third time, she knew something had to change: She decided, abruptly, to move to Brooklyn. She knew of a metalsmithing studio there where she could rent space; she couldn’t bear to be in the backyard studio Ron had built anymore. Around the same time, she discovered Families for Safe Streets (FSS), a Transportation Alternatives project made up of victims of traffic violence and their loved ones, which offered her a community that understood what she had gone through. A few years later, when the group got involved in developing the Circles for Safe Streets program, based on restorative justice principles, Robin was intrigued. She was skeptical of the criminal justice system and interested in alternatives, and she believed that Ron would have been, too.

The term “restorative justice” was popularized in the 1990s by the criminologist Howard Zehr, though he and other practitioners point out that similar approaches have been used across history, including in many Indigenous communities. Zehr outlined three main questions that should inform restorative justice practices: “Who has been hurt in this situation? What are their needs? Whose obligation is it to address those needs?” In the years since, restorative justice has gained traction among activists seeking to move away from carceral responses to violence and harm. The term is typically—though not exclusively—associated with processes in which victim and offender face each other directly, often in the presence of their loved ones; in some cases, harm-doers commit to providing financial or other forms of reparation, or to engaging in longer-term work to change their behavior. The approach has made headway in institutions: Schools around the country have begun running such programs for students, in an attempt to thwart the school-to-prison pipeline; some courts offer them as “alternatives to incarceration” for low-level and juvenile offenders. Advocates say that, in addition to preserving the humanity of the perpetrator, restorative justice better serves the victim; as Zehr has written, the harmed party is sidelined by the courts, which center questions like “What laws were broken? Who did it? What do they deserve?”

FSS worked on the Circles for Safe Streets program with the Center for Justice Innovation (CJI), a nonprofit that pursues alternatives to incarceration. In speaking to FSS members for a previous project, “I was struck by the number of people who shared what it would have meant to them just to receive a simple apology,” said Amanda Berman, the deputy director of regional programs at CJI. Most talked about feeling let down or even retraumatized by their experiences with the criminal justice system. Like Robin, many were convinced that the drivers who had injured them or killed their loved ones were not contrite: They spoke of how a driver wouldn’t look them in the eye, or never reached out to express remorse. Berman, who had previously practiced as a defense attorney, knew all too well that the court system wasn’t designed to make space for such apologies. Most defense attorneys urge their clients to avoid strengthening the case against them by acknowledging guilt. (The same is true in civil cases, where admitting fault can increase liability.) “The attorney is advising you, ‘Don’t say a word and don’t contact that person,’” said Hillary Packer, a senior associate in restorative practices at CJI.

But when CJI began holding listening sessions with drivers who had been responsible for a serious injury or death, they found that many were in fact distraught about what they had done. Deprived by the system of any chance to atone, some were living with PTSD or had contemplated suicide. “What they said repeatedly was, ‘All I wanted to do was try to make amends. I was longing to do something or say something to this person whom I knew I had deeply impacted,’” said Packer. The staff was struck by how profoundly the reality often differed from the impressions formed by victims’ families. They became increasingly convinced that restorative justice practices could better serve the needs of all involved, creating a confidential space where drivers could express remorse without legal consequences, and where victims could receive the apologies they were looking for.

Restorative justice practitioners meet for a circle during a 2018 convening held by Impact Justice and partner organizations. Photo courtesy of Impact Justice.

In the fall of 2021, shortly after I was hit on Fulton Street, New York City’s district attorneys began referring cases to Circles for Safe Streets. Most of the referrals involved drivers who had been charged with misdemeanors under the 2014 law, and who were encouraged to participate in Circles as an alternative to probation or community service; a few drivers faced more serious charges, like involuntary manslaughter, and had been offered less time behind bars in exchange for completing the Circles program. CJI also sought FSS members who would be willing to serve as surrogates for the families of victims who had been killed: While the goal of restorative justice is typically to bring perpetrators into direct accountability processes with their victims or victims’ loved ones, some programs tap survivors with similar experiences to stand in for victims who don’t feel able to participate. Seven of the 11 Circles for Safe Streets processes held so far have involved surrogates. I spoke with one driver, Gale Lawrence, who participated in such a circle after she hit and killed a woman she had failed to see crossing the street on a snowy day. The crash left Lawrence—a Brooklyn mother of two who works as a caretaker for disabled people—unable to eat, plagued by insomnia and tormented by nightmares of people dying in accidents or violent shootings. Her blood pressure shot up, and her doctor prescribed three different medications to bring it down. She stopped driving for a year. Though she thought often of trying to contact the woman’s family—maybe dropping off a wreath of flowers—people in her life cautioned her against it, warning her that she didn’t know how they would react. When she was referred to the Circles for Safe Streets program by a judge, she feared that the surrogate family she would face—the immediate family and close friend of a woman who had been killed earlier that year—might throw things at her and call her names. But to her surprise, the family comforted her, telling her that they knew she hadn’t intended to cause harm and they didn’t condemn her. After the circle, Lawrence started eating and sleeping again. Her blood pressure improved dramatically, to her doctor’s surprise. She credits the process with making her a safer driver—and it also gave her hope that the family of the woman she hit might someday forgive her. “I wished it was them that were speaking,” she told me. “I began to think maybe one day they would go to Circles for Safe Streets and we could talk.”

Among the FSS members who volunteered to serve as a surrogate was Robin. Her interest was not just intellectual: Because she believed that the driver in Ron’s case had failed in “recognizing Ron’s humanity,” she hoped to receive that validation from another driver. On the day of the circle, Robin’s niece went along to support her; the driver brought her husband and brother. Each participant had met with facilitators for preparatory conversations and had a turn to speak during the circle itself. Hearing the driver—who had hit and killed a woman in a crosswalk because she didn’t see her from behind the wheel of a large SUV—talk about her own sense of devastation provided Robin with “a transfusion of compassion that I had sorely needed,” she said. Robin was grateful, too, for the chance to hear her niece talk about how Ron’s death had affected her: “She said she lost her uncle, but then she lost her aunt, because I was so gone for a while. She’d never said that to me before.” Above all, it helped her to know that, even if she hadn’t received an apology for Ron’s death, there were people out there who wanted to make amends.

Still, she struggled with the knowledge that she wouldn’t be able to go through the same process with the driver who hit Ron. Because the woman hadn’t expressed remorse, neither giving a statement in court nor reaching out in private, Robin found it hard to imagine that she would be a good candidate for a restorative justice program. This feeling was compounded by the fact that, though the woman had been sentenced to reimburse Robin for Ron’s funeral costs—at a modest monthly rate—Robin had never received any payments. Robin was aware that some drivers were legally advised not to apologize, but she didn’t believe this applied in Ron’s case because the driver had pleaded guilty, effectively admitting culpability. “I was sad when I realized, well, my case would never have worked [for a circle],” Robin said in that first conversation. “There’s never going to be any apology to me for Ron.”

As the first Circles of Safe Streets sessions kicked off, I was busy wading through the legal and medical bureaucracy that awaits the American crash victim. Vaccaro, the lawyer I hired to help me secure coverage of my medical bills and additional personal injury compensation, began calling the local police precinct, haranguing them to track down the offending van so we could obtain the insurance information. Perhaps thanks to his persistence, the police took the step of opening an investigation, collecting a photo of the license plate taken by a witness, and calling in the registered owner for questioning. According to files I recently received through a public records request, the owner told a detective that her “common law husband” used the van for “transporting kids’ bouncy houses and such.” (I later deduced that he owned a small company that put on children’s birthday parties.) She said she didn’t know which of his employees was driving at the hour of the crash, and the police were ultimately stymied by the fact that no one would admit to being the person behind the wheel. The detectives closed the case on December 9th, but not before giving Vaccaro the name of the vehicle’s insurance provider, which eventually paid for the care I received after the crash.

The woman who owned the van that hit me said she didn’t know who had been driving at the hour of the crash, and the police were ultimately stymied by the fact that no one would admit to being the person behind the wheel.

At the end of October, I returned to running, beginning slowly as my ribs adjusted to holding rapid breaths again. Just before Thanksgiving, Vaccaro called to tell me that the insurance company had agreed to pay me a hefty settlement on top of footing my hospital bills, as long as we promised not to go after their client for more money. He also mentioned that the car’s registered owner had finally told the insurance company the name of the man who had hit me. I immediately googled him but found almost nothing: a couple of Facebook pages without public posts; a sparse Whitepages entry.

When I decided to search for R. in earnest, a year and a half later, those scant leads proved hard to follow. I slipped a letter under the door of the address I had found on Whitepages, and received a call the next day from a man whose name was indeed R., but who swore he hadn’t been involved in any accident; he hadn’t driven a car in five years. When I got my investigative file from the police, I remembered that there had been a second R. on Facebook who had listed his employment as, sure enough, a kids’ entertainment company. I sent him a friend request and a message. No response. I began calling the company; the receptionist didn’t know what to do with me, said she didn’t know any R. I found the name of the company’s owner, presumably the “common law husband,” and tried calling him. Number out of service. I sent him a Facebook message. Nothing.

My big plan to find R. had rolled to an anticlimactic halt. In reporting on the Circles for Safe Streets model, I had started to wonder whether we could have participated in something similar. But how do you forgive someone who doesn’t want to make amends with you? What about someone you can’t find? My story seemed like the kind of data point law-and-order politicians might savor: Big city is rife with lawless hooligans after all! Not everyone is going to want to sing kumbaya with you! Etcetera.

I mentioned my failure to find R. in a conversation with Cymone Fuller, director of the Restorative Justice Project at Impact Justice, which aids communities across the country in implementing restorative justice programs. Fuller acknowledged that because of the practice’s Indigenous origins, many of its techniques were designed for tight-knit communities in which everyone knew each other, rather than for incidents involving strangers, like R. and me. “Part of what is challenging about the application of restorative justice now is that we are also having to build community as we try to repair relationships,” she said. In the contexts Fuller was describing, harm-doers might take part in restorative justice processes out of a sense of obligation to the people around them, or a fear of losing their place in their communities; the model available to me, on the other hand, relied on drivers like R. feeling a personal desire to atone.

I had struck out on finding R., but I still had to look for the woman who hit Ron: In order to include Robin’s impressions of her, I would need to give her a chance to comment. I had begun to group R. with this woman in my mind—harm-doers who seemed unwilling to own up to their actions in the way that a restorative justice program like Circles for Safe Streets would require.

Everyone I spoke to who had been involved in Circles for Safe Streets stressed that the program is only appropriate for certain cases of traffic violence—an important option, but not a blanket replacement for all criminal proceedings. For one thing, Packer said, CJI will only set up a circle if the driver accepts responsibility for their role in the crash. (While that might seem to exclude hit-and-run drivers, Packer told me that CSS has run circles with several such perpetrators, including one who fled in a panic and returned two hours later.) When I discussed the program with Vaccaro, he cautioned me that in his career as a civil attorney, he

had seen countless drivers avoid owning up to causing harm; he laughed when I suggested that some might be looking for a chance to express remorse. “There’s got to be at least three people like that,” he said. On the victim’s side, the process requires a willingness to hear directly from the driver. “We don’t screen out harmed parties who are not feeling compassionate toward the driver,” but “you have to be open to listening to this person,” Packer said. This may demand a particular disposition. Tom Proctor, a Families for Safe Streets member whose brother, Charlie, was killed on his bike in a town outside Boston in May 2020, participated as a surrogate in a circle that took place this year—but said he doesn’t believe that many of his family members would be interested in such a process with the driver who hit Charlie. Tom’s wife, Sandra Voss, who attended the circle with him, pointed out that Tom is personally inclined toward “system blaming” rather than “individual blaming.” (Indeed, when we spoke, he emphasized the flawed design of the intersection where his brother was killed, placing fault with “a society that doesn’t pay serious attention to questions of road design.”) “I think Tom is very low on the anger spectrum,” Voss said. When families decide they are too angry to listen, Packer said that CJI may try to find a surrogate, or ultimately choose not to proceed.

Through reading old news reports, I found the name of the driver who hit Ron, Anna. After a few days of searching, I stumbled on her Facebook page and sent her a friend request and a message about the story. I held out little hope of a response. But the very next morning, Anna (who asked that I use only her first name) sent me a polite note saying that she was open to talking. A few days later, she joined our scheduled Zoom call from her phone, wearing a baseball cap and standing outside the auto shop near the Jersey Shore where she works fixing cars and doing oil changes.

I had expected someone detached and guarded, but Anna, now 26, was emotionally open and expressive, candid about how deeply the crash had affected her life. In its immediate aftermath, she had become depressed and nearly suicidal, turning to heroin and cocaine to cope. “I just couldn’t comprehend the fact that I did that, and just how much harm I caused to his wife and his sisters,” she said, through tears. The county where Ron was killed didn’t have a woman’s jail, so she spent her six months of incarceration—including her 21st birthday—in a neighboring county, a bit farther from family. The cells were often overcrowded; it was too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter, and the showers were moldy and full of gnats. There was little therapeutic help available. When Anna was released, she went back to using drugs. To fuel her habit, she stole jewelry from a family member; because she was still on probation, she got sentenced to seven months in prison. It took her several years and multiple rehab stints to get clean. Today, she has the support of a psychiatrist and therapist. Still, the guilt remains. “[Treatment] has helped, but I just, I don’t know—how do you get over something like that?” she said, her voice breaking. “Or not necessarily get over it, but learn to deal with it. I still think about it all the time.” Though she likes her current job, her criminal record has made it more difficult to find work. While she didn’t pay the restitution in the phase she spent rotating through rehabs, she told me she’s been paying it for the past year. (When I relayed this to Robin, she realized she needed to send the court her new address.) Anna became eligible to reclaim her driver’s license several years ago but put it off until this summer, riding an e-bike to work, afraid of getting behind the wheel. Driving still makes her nervous.

Ron and Robin in New York City’s Central Park in 2012. Photo courtesy of Robin Middleman Filepp.

“How do you get over something like that? Or not necessarily get over it, but learn to deal with it. I still think about it all the time.”

Anna also had different information to offer about the crash itself. Contra the prosecutor, she told me that it was she, not her mom, who called the police that day seven years ago. She says she believed that she’d hit an animal when she spaced out briefly behind the wheel and felt an impact; she looked back but didn’t see anything in the road, because Ron had fallen off to the side. She texted her girlfriend about hitting a deer when she got home, and decided to report an accident when she saw that her car was damaged. She told me she only realized something more serious had happened when state troopers and local police officers showed up at her house and arrested her. When I asked about the second text, she said she might have sent a follow-up when the police showed up, but she doesn’t remember the details. As for the trial, her memories are hard to access, the details mostly “blocked out,” she said. She recalls Robin’s victim-impact statement at the sentencing hearing, and how she showed the room a painting she had made of Ron. She regrets not speaking at the hearing, but at the time, it seemed too hard. “I feel like if I had opened my mouth, I would have just lost it. I don’t know if I would have been able to pull myself together.” She said the court proceedings felt almost designed to portray her as a “bad person,” leaving little room for her deep remorse; her public defender didn’t spend much time preparing her for the proceedings. She didn’t feel that she had much opportunity “to show that I was genuinely sorry, and genuinely upset, and felt so guilty for what I did.”

I asked Anna if she had ever considered getting in touch with Robin to apologize. She said she thinks about it all the time. She has often imagined writing a letter, but she said the paperwork she received from the court about her sentence stipulated that she’s not supposed to contact the victim’s family as long as she’s on parole, which she will be until later this fall. She’s also never been sure whether Robin would welcome a message: “Does she want me to reach out and apologize, or would it upset her? I don’t want to cause any more damage than I’ve already caused.”

A couple of days after my call with Anna, I met with Robin at the bakery where we’d talked the previous month, in the Brooklyn neighborhood where we both live. She had dyed her hair turquoise for a music festival she’d just attended in Hawaii, where she heard the rock musician Todd Rundgren—a favorite ever since she discovered his songs among the recent plays on Ron’s iPad after his death. I summarized my conversation with Anna. Did it make her feel differently to know that Anna actually did think a lot about Ron? Robin took a sip of her coffee and thought it over. She said she had mixed feelings. It was painful that the information was coming almost seven years too late to affect what she’d gone through in the wake of Ron’s death. She still felt the lack of an apology acutely, and wasn’t fully convinced that Anna had been legally barred from contacting her. The fact that Anna hadn’t looked at her in court still gnawed at Robin. Back then, “the way I was feeling was so raw—I was looking for anything. I wouldn’t have hesitated for a second if she had made some gesture of apology,” she said. She still believes it was appropriate for Anna to get jail time after driving away from the scene. But Ron was a “forgiving person,” and Robin wanted to respond in that spirit. She might be prepared to speak to Anna, or at least to accept an apology in writing. She told me she would have to think about it.

Even as the popularity of restorative justice has grown, it has yet to become anything approaching a standard option for responding to criminalized forms of harm—and it is especially uncommon as a response to traffic violence. Circles for Safe Streets appears to be the only program of its kind in the country, and has run just 11 circles in the two years since its launch, largely due to limited funding, which restricts staff capacity. The existing legal landscape also presents obstacles. Packer recounted two cases in which a driver and a seriously injured victim were eager to sit down with one another, but their civil attorneys ended up nixing the process, fearing the parties’ candor could impact their case.

Perhaps the thorniest question is whether restorative justice can work in tandem with the criminal courts in particular. There is considerable debate among theorists and practitioners about the value of efforts like Circles for Safe Streets that operate under the auspices of the carceral system even as they seek to subvert its logic. Some prison abolitionists criticize such programs for collaborating with prosecutors and judges, allowing the court system to put on a friendly face while retaining the power to incarcerate. Berman of CJI acknowledges the tensions inherent in the organization’s relationship to New York’s district attorneys offices: Working within the system provides some “leverage” to get people to participate, she said, but facilitators “don’t want anyone to be coerced. It has to be voluntary.” How can they assess whether a driver is truly ready to take accountability when the person may be motivated by a desire to avoid fines or jail time? Then again, how many people would actually show up absent the threat of criminal consequences? “We worry about co-optation all the time,” Fuller of Impact Justice told me.

Some abolitionists, like the writer and organizer Mariame Kaba, have warned that trying to slot these radical practices into the existing system can place dire constraints on our collective imagination. “I reject the premise” that restorative justice efforts are “alternatives to incarceration,” she said on The Appeal’s podcast Justice in America in 2019. “When I say ‘alternative to prison,’ all you hear is ‘prison’ . . . it conditions your imagination to think about the prison as the center . . . And here we are in this position where all you then think about is replacing what we currently use prisons for.”

Still, some advocates see court-affiliated restorative justice programs like Circles for Safe Streets as opportunities for prison abolitionists to prove that the carceral system can be displaced: “The goal is that we get to the point where we don’t have to frame [these programs] as an alternative [to incarceration]—that it’s actually a baseline, a default,” said Berman. “In order to get there, though, you have to be willing to offer alternatives.” In the process, Fuller argues, we can begin to build a society predicated on stronger bonds. “It’s a restorative experience in and of itself to be accountable when you’ve done something, to be able to say, ‘I’m sorry, I’ve done this, and I want to figure out what I can do to make things right,’” she said. “It’s also a reminder that you’re a part of something bigger than yourself—you’re part of a community that wants to see you do better.”

Robin’s experience initially struck me as an example of the ways a restorative justice approach might fail to contain the scope and complexity of human behavior, but now it seemed like evidence of its urgency.

But such opportunities remain rare. A week and a half after our second meeting, Robin texted me to let me know that, after giving it deep thought, she decided she didn’t feel up to speaking directly with Anna. She fears that doing so could endanger the progress she has made toward stability in the wake of Ron’s death. In the days after receiving her message, I wondered whether a restorative justice process like the ones run by Circles for Safe Streets could have mitigated the suffering that both Robin and Anna experienced after the crash. If Robin was looking for Anna to acknowledge the harm she had caused, and Anna was seeking a way to process her guilt, it seemed clear that the criminal justice system had failed to make space for either. With Berman and Packer’s approach, could their story have played out at least a little bit differently? Robin’s experience initially struck me as an example of the ways a restorative justice approach might fail to contain the scope and complexity of human behavior, but now it seemed like evidence of its urgency.

Talking to Anna had made me feel hopeful that many harm-doers might be willing to take responsibility if they were offered the right opportunity to do so. Still, I had to respect the fact that making contact with her might not mean the same thing to Robin. In a sense, I had stumbled into the role of the surrogate, receiving answers from Anna that I had hoped to get from the driver who hit me. But this didn’t supplant my unresolved relationship to R., or change Robin and Anna’s unresolved relationship with one another. Their story, like mine, had reached an impasse.

Sometimes, crossing a busy street still unsettles me; I don’t fully trust cars to stop at the red light. When I walk up Fulton Street to meet friends, I hold my breath a little as I pass the crash site. I have often taken comfort in the city’s promise of anonymity, savoring the feeling of being unknown. Can we make this expansive metropolis a place where, if R. hit me with a car, he would feel some sort of obligation—toward me, or toward others in his community—to stay and take responsibility, without the threat of a cage? I’ll admit that I still sometimes struggle to see how we would actually get there. But I am trying to let go of the idea that a solution has to do everything in order to do something. Even if some harm-doers seem unrepentant, there are more people than we might expect who want to make amends. It’s at least a place to start.

Mari Cohen is associate editor at Jewish Currents.