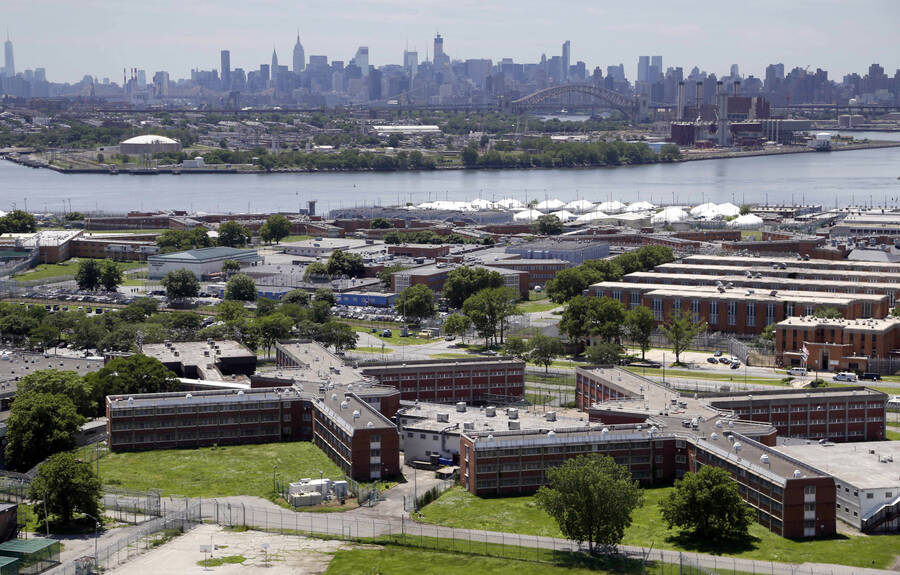

The Rikers Island jail complex in New York.

WE WERE INSTRUCTED not to bring anything that could be construed as a weapon. Other volunteers had packed printed haggadot, nature valley bars, assortments of fresh produce, water bottles, and period products. I had only a notebook and my wallet; I didn’t even bring a pen. I thus enjoyed a relatively painless security process upon entering the biggest jail on Rikers Island, the Anna M. Kross Center, where that night’s seder was to be held.

At its inception a decade ago, the volunteer program consisted mainly of rabbinical students at the modern orthodox yeshiva Chovevei Torah who led all kinds of Jewish services at Rikers. Over the past few years, the volunteer pool has become increasingly secular. When the pandemic began, Rikers stopped allowing volunteers to stay overnight, which foreclosed the opportunity for the religiously observant to participate in the program. There hadn’t been a volunteer-led seder at the jail complex since 2019.

The first thing I noticed upon entering the jail was an implacable din. As we were led down a beige hallway plastered with NO TALKING signs, this boundless noise, like the roar of a thousand window ACs, filled the entire building and crowded my every thought. Even the metal gates which slid open and clanged shut behind us were muffled; the only thing that kept an encroaching panic at bay was knowing that there was nowhere for it to go. Only snatches of conversation between correction officers cut through the noise. Several inmates, silent, beige-clad, escorted by officers, walked past us. The idea of a seder—a ritual designed for intimate conversation—proceeding under these circumstances felt impossible, almost perverse.

The hallway led us to a massive multi-purpose room, not unlike ones I grew up eating lunch, having PE class, and attending high school dances in. The floor was marked like a basketball court. The COs mostly sat around on bleachers while incarcerated attendees, some of them bussed in from different parts of the island, filed into the room. A volunteer provided them with stickers on which they wrote their names, their pronouns, and their favorite thing about Passover. Under her name and pronouns, an East Asian woman with a braid that ran almost to her waist had written “Mashiach.” I focused on setting up seder plates with a few other volunteers, channeling a mounting feeling of unease into arranging ingredients that had been squished or otherwise compromised in the transportation and security processes into a reasonably appealing presentation. The charoset—the paste, rather than the superior chunk variety—had smeared across several of the plates. There were not enough orange slices for every seder plate. Rabbi Yaakov, a young, shortish Chabad rabbi with an impassioned disposition floated around from table to table introducing himself to the attendees.

CLAP THREE TIMES IF YOU CAN HEAR ME. CLAP THREE TIMES IF YOU CAN HEAR ME. Scattered clapping eventually drew the room’s attention to Rabbi Yaakov, who began the service by shouting: Why are women tasked with lighting the Shabbat candles? Several incarcerated women were seated together at a long table set with tea candles. After saying the prayer, one woman went to light the candle in front of her, and a CO rushed forward and grabbed the lighter in her hand. “They’re not allowed to have that,” she said. We moved on to Kiddush.

When it came time for me to sit down I was overcome by a feeling of sheepishness, like a new student facing a cliqued-up cafeteria. I decided to join a group of three men. Two of them were engaged in what appeared to be a serious conversation, so I asked the third some questions to help me orient myself: What did the different colored jumpsuits mean? Did any of the attendees know one another prior to that night? He explained that the jumpsuits corresponded to particular jails; he only recognized a few faces from other Jewish programming.

Because the room was so large and the jail so loud, Rabbi Yaakov could only really commandeer a few tables’ attention at once. Other tables had atomized, worlds unto themselves, maintaining their own conversations, their own moods. At one point, the rabbi—perhaps sensing the fractured attention—hoisted a man onto his shoulders and launched into a lively rendition of “Am Yisrael Chai.” The entire room united in song; the COs bristled in the bleachers. When it came time to dip the bitter herbs into the tears of our ancestors in bondage, the room once again fell into disjointed conversation.

As I spoke to more people, I learned that the vast majority of attendees had converted to Judaism while detained. “When you look at history, it seems like the Jews have had more faith than anyone,” a young man named Dennis told me. A man with pale green eyes and a Star of David tattoo on his cheekbone explained that he was a Rastafarian who discovered the ways Judaism resonated with him at Rikers, in a moment where faith had become a necessity. Another man had converted because it was the fastest way to marry a woman he met on a bus ride to court. He gestured toward one of the women at the women’s table. Because the men and women were not allowed to intermingle, his wife asked a CO if they could swap masks—a paltry quasi-intimacy. The CO said no.

One man, who sat with the small group of white guys at the front of the room, had punctuated the seder with small acts of mischief, kicking his feet up during the Maggid and heckling the rabbi with seemingly random outbursts, sometimes a groan, sometimes a cheer. As the rabbi led the room in the longer, more traditional versions of the songs and prayers I grew up with, the man’s focus shifted and he began to sing along. His prayer became increasingly passionate, and his voice took on a bright, crystalline quality which pierced the ambient noise and several layers of conversation. At one point, he stood up on a chair and pulled a tallis out from under his jumpsuit. Everyone was stunned; it was the closest thing to silence the room had heard all evening.

At the end of the night, we helped attendees collapse tables and chairs, and stacked them along the walls. In the course of mere minutes, the site of our seder was an indoor basketball court again. I shook hands and exchanged goodbyes with various people I had spoken to. Several asked if I would be returning for the second night of Passover. I replied that I wouldn’t be. There was no natural rejoinder to our parting. The buses came back to take the celebrants back to the jails they’d come from.

Nobody spoke as the volunteer car made its way over the bridge connecting Rikers Island to Queens. The persistent rumbling of the jail, which I had forgotten was there, eventually dissipated. The Manhattan skyline loomed larger and brighter as we hurtled back toward the quieter place we had come from.

Arielle Isack is a former Jewish Currents fellow.