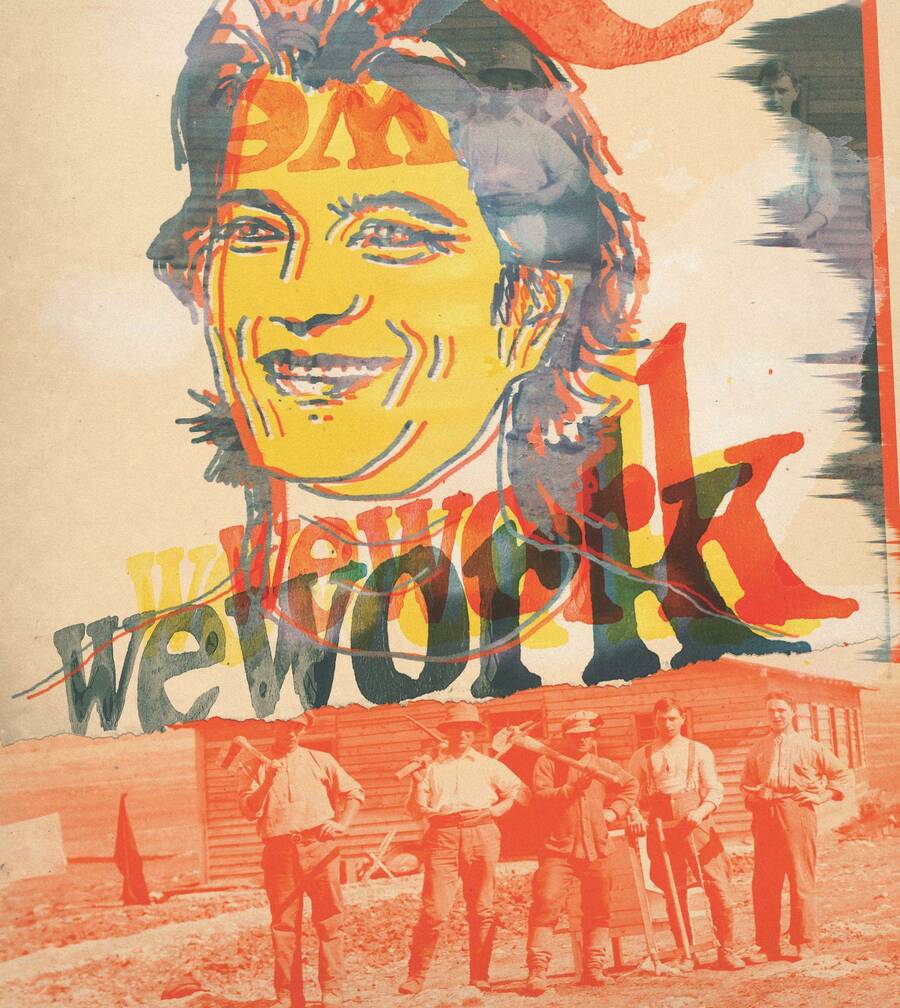

The Capitalist’s Kibbutz

WeWork sold Wall Street a fantasy of Israeli communal living with an entrepreneurial twist—until it collapsed.

ADAM NEUMANN was a 31-year-old Baruch College dropout when he arrived at a 2010 real estate industry conference on Park Avenue and boasted that his months-old company, WeWork, would one day replace JPMorgan as the largest leaser of office space in New York City.

Neumann cut a striking figure—six-foot-five; shoulder-length, surf-tossed hair; a t-shirt and jeans in a sea of suits. What attendees would remember most about him, though, was not his look but his story. Neumann was born in Be’er Sheva in southern Israel and spent several years of his childhood on Nir Am, a kibbutz in the northwestern Negev, a few miles from Gaza. In early meetings with investors, and in the magazine profiles that would soon follow, Neumann invoked the values he absorbed on the kibbutz as foundational to the DNA of his company. “If you understand that being part of something greater than yourself is meaningful,” Neumann told The New York Times in 2015, “and if you’re not driven just by material goods, then you’re part of the We Generation.”

Neumann presented WeWork as a pioneer of the “sharing economy.” With Uber and Airbnb, the company was among the first to substitute the ambiguously egalitarian word “share” for the candidly exploitative “rent”—a neat attempt to incorporate youthful dissatisfaction with inequality and isolation into a sales pitch for recession-era commodities. As Uber had disrupted taxis, Neumann intended to disrupt office rentals. He marketed his sublets to contingent but reasonably well-paid no-collar workers who, as Neumann put it, sought to “make a life, not just a living.” WeWork’s distinctive design (concrete floors; wrought iron; unpolished wood; neon signs) together with its New Age dorm room amenities (beer and kombucha on tap; foosball tables; yoga classes) refined the image of the “start-up” in the popular imagination. To many clients—often other tech-adjacent companies in their infant stages—WeWork wasn’t just selling office space; they were selling a style, a costume, an aesthetic of youthful entrepreneurial verve that was, for a time, irresistible to Silicon Valley investors.

Neumann’s vainglorious personality—and the ambitious, idealistic story he told about his company—attracted fawning media attention and billions of dollars in venture capital. As WeWork grew, Neumann took to traveling by $60-million private jet and investing in vanity projects, like a company that designed wave pools and another that sold turmeric coffee creamer. He intimated that an empire was in the making, including a handful of residential (WeLive) apartments pre-adorned with WeWork’s signature industrial-chic aesthetic, and a for-profit elementary school (WeGrow) developed by his wife Rebekah Neumann (née Paltrow; she is Gwyneth’s cousin). Neumann boasted of plans for WeSleep (a boutique hotel), WeSail (luxury yacht rentals), and WeBank (financial services). “WeWork Mars is in our pipeline,” he said in 2015.

Meanwhile, Neumann started to fancy himself a diplomat. Much of WeWork’s venture capital came from SoftBank, a Japanese conglomerate flush with cash from Saudi Arabia’s state-owned sovereign wealth fund. As the Saudi money poured in, Neumann cozied up to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, suggesting to colleagues that he and bin Salman were working together to “save” Saudi women by offering them coding classes. Neumann also counseled Jared Kushner, a friendly rival from their days as New York City real estate muckety-mucks (and whom he once beat in an arm wrestle to settle a business dispute), on his Mideast peace plan. Neumann later bragged to associates that the trio—bin Salman, Kushner, and himself—would save the world.

WeWork did manage to surpass JPMorgan in New York office rentals in September 2018, but it also failed spectacularly to make money. Last year, after a series of damaging financial disclosures and press reports, investors balked, the company nearly collapsed, and Neumann was pushed out as CEO. With its projected value plummeting, the company’s new leadership indefinitely postponed the initial public stock offering (IPO). WeWork’s survival, analysts say, will now depend on stripping away its aesthetic excesses, as well as thousands of jobs, to focus narrowly on what it actually is: a commercial real estate company, not unlike co-working competitor IWG. (The latter, notably, is worth 15 times less than WeWork at its peak valuation, earns double the revenue, and turns a profit.)

How did a company that sublets office space manage to become a cutting-edge global brand worth tens of billions of dollars? Like many founders before him, Neumann had the good sense to express his megalomania and greed in the language of community and social change. He took the ideological blueprint provided by previous Silicon Valley behemoths—Google’s “Don’t Be Evil”; Facebook’s aspirational globalism—and distilled it to an essence. “The past ten years was the decade of ‘I,’” Neumann declared in 2011. “This decade is the decade of ‘We.’”

Neumann’s gambit was the apotheosis of a process set in motion half a century earlier by marketing gurus who discovered the communitarian sensibility of the counterculture could be divorced from its transgressive, egalitarian ethos—and used to sell products. (This revelation is memorably depicted in the final scene of AMC’s Mad Men, which finds Don Draper meditating on a California bluff, apparently conceiving Coca-Cola’s hippified 1971 ad “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke.”) So shameless and total was Neumann’s drive to commodify the image and affect of togetherness that he trademarked the very word “We”—and sold it to his own company for $5.9 million. (Facing backlash, he later returned the money.)

Neumann deployed his kibbutz backstory in service of the same sleight of hand, garnishing WeWork’s commercial aims with an air of cooperative altruism. The problem with the original kibbutz, Neumann said, was its socialism; real kibbutzim represented a “failed social experiment” because “everyone made the same amount of money.” By separating the communal form from its democratic content, WeWork would succeed where its predecessors failed. He called it “Kibbutz 2.0.”

Ironically, while the American workplace was becoming an ersatz kibbutz, the Israeli kibbutz was hurtling toward 21st-century capitalism from the opposite direction, embracing not just privatization and the stock market but tech entrepreneurship. The story of WeWork, like the story of the kibbutz, demonstrates both the power and the limits of painting over exploitation with a veneer of collectivist idealism. Neumann’s financiers hoped dead utopian forms could provide a pleasing, communitarian skin for a new capitalist colossus. But, for a variety of reasons, the gambit failed; the façade wouldn’t hold. And in the end, WeWork’s spectacular fall implicated not just Wall Street and Silicon Valley, but the founding myths of both Israel and the United States, two nations clinging to metaphors whose potency may soon expire.

STATES, LIKE START-UPS, NEED METAPHORS: a story to turn earth and mountain and sand into a country, frail and traumatized human beings into a nation. In the case of settler states, they need images to invent a terra nullius, “a land without a people for a people without a land.” The United States had “the frontier” and the hardy homesteaders who settled it, building small subsistence farms in an untamed wilderness. Israel had the kibbutz.

The earliest kibbutzim were communal farms founded by ideologically committed Zionist settlers in the early 20th century. Though little more than 7% of the Israeli population ever lived on a kibbutz, the institution served a quintessential role in the Israeli imagination. In the Yishuv period, before the founding of modern Israel, the kibbutzniks were said to have “made the desert bloom”; after 1948, the kibbutz came to symbolize the hardscrabble crucible in which a “new Jew” was to be formed. As British historian Tony Judt put it, remembering his time as a committed labor Zionist in the 1960s, the kibbutzim represented “the idea that young Jews from the diaspora would be rescued from their effete, assimilated lives and transported to remote collective settlements in rural Palestine—there to create (and, as the ideology had it, recreate) a living Jewish peasantry, neither exploited nor exploiting.” In the Zionist imaginary, the kibbutznik was the opposite of the diasporic Jew: one feeble, the other strong; one cosmopolitan, the other rooted; one selfish and acquisitive, the other communal, concerned with providing what was needed—with “making a life, not a living.”

Like the yeomen farmers of the American frontier, the metaphorical aura of the kibbutz was necessary to conceal a less attractive, literal purpose: the founding of a nation-state on the basis of racial exclusion, the expropriation of land, and the exploitation of labor. Nir Am, where Neumann spent some of his childhood, was the site of a brutal torture and execution of an Arab man by Jewish paramilitaries during the ’48 war. The kibbutzim—some deliberately founded in strategic, outlying regions in the 1930s—defined the borders of modern Israel and established the division of Jewish and Arab labor by banning Arab members. They served as military outposts in wars of colonial conquest and created a template for settler expansion. They have also produced a disproportionate number of Israeli military elites and politicians; as recently as 2000, 42% of the Israeli Air Force came from the kibbutz sector.

Contra Neumann’s founding mythos, socialism has been going out of fashion on the kibbutz for decades. Most kibbutzim embraced “Kibbutz 2.0” before Neumann was out of grade school. In the aftermath of a severe debt crisis in the 1980s—which exacerbated long-held complaints among members about the lazy “parasites” who failed to contribute their fair share of labor—many kibbutzim began to privatize, pay market wages, and sell shares in their industries on public stock exchanges. A majority of kibbutzim today pay differential wages; indeed, some suffer high degrees of inequality, with the lowest-paid workers earning many times less than the highest. Many kibbutzim still engage in collective decision-making processes, but financial matters are left to business managers, not a rotating cast of neighbors. In other words, the kibbutzniks have embraced Neumann’s dictum, as he put it to New York magazine: “On the one hand, community; on the other hand, you eat what you kill.”

Today, Nir Am hosts a co-working space for the start-up incubator SouthUp featuring a full bar, pool table, and WeWork-like decor. Many kibbutzim have sought to cash in on the profits coming out of Silicon Wadi, as Israel’s booming tech scene is known. Together, kibbutzim have invested 110 million shekels ($31.8 million) in 34 start-up equity deals in the past five years. Some are host to incubators like Nir Am; Revivim built one inside its former hatchery (to literalize the metaphor). Others allow their funds to be invested in promising innovations, especially those that overlap with local industries. “I’d rather be rich with a lot of people, than a lonely rich man,” Lion David, co-founder of the start-up incubator at Revivim, told the Christian Science Monitor. “We want people to come and say, ‘Let’s make millions of dollars together.’ And we don’t have to sell our soul for it in the city by ourselves.”

Even as the kibbutz became capitalist, its utility as mythology has remained. The metaphor of the kibbutz transmuted WeWork’s banal business model into something more—more ambitious and altruistic, a utopian project with prophetic dimensions. At WeWork, customers weren’t tenants but “community members”; the hallways and stairwells were narrow not to save money, but to encourage camaraderie and spontaneous encounters. Neumann claimed WeWork existed to “elevate the world’s consciousness.” He promised to “define a new world in which it is possible to be owners of nothing and have access to everything.” He admitted, in 2017, that WeWork’s “valuation and size today are much more based on our energy and spirituality than it is on a multiple of revenue.” Where accounting fails, imagination fills the gap. Neumann helped investors imagine communities.

THE “ISRAELINESS” OF WEWORK’S ETHOS, as a 2017 Haaretz article termed it, was an essential part of Adam Neumann’s pitch to Wall Street and Silicon Valley—and back in 2010, investors were particularly eager to hear it. As national economies lurched back to life in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, a narrative emerged in the Western business press that Israel had weathered the global collapse thanks to its uniquely dynamic entrepreneurial sector. “Israel has more high-tech start-ups per capita than any other nation on earth, by far,” wrote New York Times columnist David Brooks at the time, “It ranks second behind the U.S. in the number of companies listed on the Nasdaq. Israel, with seven million people, attracts as much venture capital as France and Germany combined.” Brooks referred to Israel’s technological success as “the fruition of the Zionist dream.”

The post-crash years saw a wave of articles and books celebrating Israel’s vibrant start-up ecosystem. These works tended to recycle easy tropes about Israeli exceptionalism, merging them with then-ubiquitous bromides about “disruptive innovation.” In 2009, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) published Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle. The book’s authors—Saul Singer, a former editorial page editor at The Jerusalem Post, and Dan Senor, a CFR fellow who had served as an advisor to the US-led occupation of Iraq—cautiously avoided the pseudoscientific ethnic essentialism that often characterizes attempts to account for Jewish ingenuity. Instead, they settled on three sociological factors to explain the phenomenon: Israel’s liberal immigration policy (for Jews), government spending on research and development, and—most importantly—universal conscription.

Thus, Senor and Singer linked Israel’s tech boom to the imperatives of maintaining regional military hegemony. Most of the entrepreneurs they profiled served in the technical branches of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). The IDF, the authors wrote, inculcates “maturity,” “adaptive problem solving,” and nimble teamwork; it generates dense human capital networks of future business, tech, and financial leaders; and, unlike more hierarchical militaries, it encourages “rosh gadol”—that is, a big-headed willingness to question authority, think outside the box, and lead. The authors and their interview subjects saw the United States as lagging behind in these areas. “When it comes to U.S. military résumés, Silicon Valley is illiterate. It’s a shame,” Israeli entrepreneur Jon Medved laments in the book. “What a waste of the kick-ass leadership talent coming out of Iraq and Afghanistan.”

In her 2019 book, Chutzpah: Why Israel Is a Hub of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, tech investor and former IDF intelligence officer Inbal Arieli regurgitates many of the same arguments in Start-Up Nation, this time with less caution about cultural essentialism. In addition to R&D and conscription, Arieli cites Israelis’ communal instinct. “In Hebrew,” she writes, “the root of the word for ‘I’ is an; this is also the base for the word for ‘we’ or ‘us’ (‘I’ is ani; ‘we’ is anu or anachnu.) The ‘I’ and the ‘we’ are inextricably linked here.” Israelis, she writes, have managed to maintain a “positive tension” between the collectivist and individualist impulse. She attributes this to the “arduous task” of building a state composed of Jews from all over the world. Israeli entrepreneurs, Arieli intimates, need not choose between generation “I” and generation “We”; they are one and the same. Or, as Neumann would often preach to his employees, one doesn’t have to choose between making the world a better place and making boatloads of money.

Neumann, who exemplifies chutzpah and rosh gadol, might as well have walked out of the pages of Start-Up Nation. He served for five years as an IDF naval officer before moving to New York City, and has often linked this experience to his vision as a founder. “There are Israeli qualities that are hard to teach,” he told Haaretz. “Someone who has served in the army has given of himself to the country, and will also know how to give of himself to the company.” Neumann’s navy comrade Ariel Tiger served as CFO of WeWork (reports on Tiger’s role in maintaining a sense of fear and precarity among staff suggest he lived up to his name). Describing the bunker-like, missionary culture of the company, a former employee told Vanity Fair, “It was like we were at war together.”

THEY LOST THE WAR. In the story relayed by WeWork’s Wall Street underwriters, the company’s unviability became evident only last summer, when a Securities and Exchange Commission filing revealed the extent of the start-up’s radically agnostic approach to profit, its byzantine corporate structure, Neumann’s egomania and conflicts of interest, and the accounting voodoo underlying its claims to future solvency. The banks and venture capitalists that had pumped billions into WeWork ran for the door, then tried to downplay their complicity. Goldman Sachs, for instance, reportedly lost $80 million on the pulled IPO, yet its CEO David Solomon told an audience at Davos this year that the process—while “not as pretty as everybody would like it to be”—had worked. According to this narrative, public market investors saw the corroded disarray under WeWork’s hood and backed away.

But that story is a self-serving gloss. Long before the aborted IPO, Neumann was a well-documented train wreck. Despite all the maturity inculcated by his military service, Neumann, by his own account, spent his first years in New York haphazardly chasing women and riches. His first two failed companies are a psychoanalytically rich testament to his arrested development. The first was a designer shoe for women with a collapsible high heel. The second, called “Krawlers,” sold a line of baby clothes with built-in kneepads. (The tagline: “Just because they don’t tell you, doesn’t mean they don’t hurt.”) As early as 2017, The Wall Street Journal’s Eliot Brown described WeWork as a start-up “fueled by Silicon Valley pixie dust.” The company has long been accused of creating a permissive, unsafe, and sexist work environment. In a lawsuit filed in 2018, one employee blamed WeWork’s “entitled, frat-boy culture” for enabling multiple assaults, including her experience of being groped by a coworker at the company’s annual Coachella-esque “Summer Camp” the year before.

In reality, WeWork true believers—the investors who allowed the company to expand to 485 locations in more than 100 cities in 28 countries, “blitzscaling” its value up to $47 billion—didn’t merely tolerate Neumann’s Point Break cosplay, in-office tequila shots, drug use, or other antics; they embraced it as an indelible sign of his genius. The archetypal “unicorn” founder was a creative toddler; he enveloped you in his imaginative play until you lost yourself, and your checkbook, in his world. As the stale maxim goes: VCs weren’t investing in companies; they were investing in men. And Neumann was a man of his times.

Perhaps the last. As Annie Lowrey notes in The Atlantic, “brilliant, brash, cavalier” founders from Elon Musk to Travis Kalanick to Elizabeth Holmes have been allowed—encouraged even—to run roughshod over traditional business ethics, regulations, and, often, the human beings who work for them. WeWork, like Uber, Tesla, and Theranos before it, suffered from what Lowrey calls “the curse of the cult of the founder.” But thanks, in part, to the parodic heights of Neumann’s messiah complex, tech journalists have begun writing obituaries for Silicon Valley’s romance with the “unicorn.”

Attributing WeWork’s downfall to Neumann’s hubris alone—his Icarus-like defiance, if not of gravity or the gods, then of the laws of financial physics—is a satisfying way to close the story, neatly settling its morals. (Indeed, in the lead-up to the IPO, Neumann was caught literally “flying high” across international borders.) But unlike Icarus, Neumann isn’t going to drown; he’s still going to be rich, only less so. SoftBank, WeWork’s largest investor, had announced plans to acquire what was left of the company (then valued at just $8 billion) in October 2019, agreeing to pay Neumann $1.7 billion for his equity. Now, with coronavirus further tanking WeWork’s value, SoftBank is scrapping the deal, leaving Neumann with a measly net worth of $450 million.

It’s doubtful Adam Neumann is the last pretty face or deep voice to hoodwink a venture capitalist into letting him light some money on fire. One hopes, however, that the collapse of Neumann’s chic house of cards might signal the waning viability of his particular con: disguising unfathomable avarice behind a mask of humanitarian virtue. After all, while Neumann was securing his first investors in Kibbutz 2.0, an actual experiment in communal living, mutual aid, and deliberative democracy—Occupy Wall Street—was taking shape in New York City’s Zuccotti Park. In 2011, the bankers of downtown Manhattan must have found it soothing to listen to young, fresh Adam Neumann describe his dream of a therapeutic and frictionless workplace seamlessly embedded in a fiercely dynamic innovation economy. For these bankers, investing in the “sharing economy” was a hedge against the movement growing in the streets below. Perhaps the angry young people could be reconciled to the prospect of permanent precarity if precarity could be rebranded as flexibility, renting as sharing, work as play.

Unfortunately for the bankers, young people largely refused this deal. Ten years later, WeWork is in shambles, and the kids in the streets have channeled their rage into the recently-suspended presidential campaign of democratic socialist Bernie Sanders—whose rumpled suit and brusque materialism represent a stark aesthetic and moral contrast to Neumann’s fashionable New Age consumerism. Amid the company’s implosion, WeWork’s own employees articulated a “we” that included the minimum-wage-earning workers who maintained their offices, but not their superrich founder. In a letter to management, 150 WeWork staffers wrote, “We are not the Adam Neumanns of this world—we are a diverse workforce with rents to pay, households to support and children to raise.” They requested “humanity and dignity” as they searched for new jobs, and demanded “full benefits and fair pay” for their buildings’ cleaning staff, whose union drive Neumann had tried to thwart. Now that the capitalist world system is buckling under the weight of a pandemic, young people are turning again to collective modes of mutual aid—necessitated by the absence of a sufficient social safety net—and demanding ever more radical solutions to protect each other and the most vulnerable members of our society. WeWork offered up the opportunity to consume communitarian values as a brand. But it appears members of the “We generation” would rather live them.

IN POLITICS, if not in marketing, a “we” always prefigures a “them.” In Israel, the democratic, egalitarian, secular Jewish “we” articulated by labor Zionist kibbutzniks at the nation’s founding has been all but supplanted by the capitalist, ethnonationalist, religious “we” projected by Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud Party and its Haredi and settler allies. The remaining labor Zionist parties performed dismally in the recent cycle of elections, losing support even among the kibbutzniks to Benny Gantz’s center-right Blue and White bloc. What is revealed by the Labor Party’s dissolution, the passage of the nation-state law, the demonization of Arab parties by Gantz and Bibi alike, and the puncturing of liberal two-state fantasies by the US-enabled annexation in the West Bank is not so much a corruption of the original Israeli “we” as the inevitable unwinding of its internal contradictions.

For its part, the labor-hungry Israeli tech sector has sought to articulate a more capacious “we”—at least for coders. Leaders in Silicon Wadi have even flirted with anti-authoritarian rhetoric, calling for Bibi to resign last November. Some, like Itzik Frid, have suggested that integrating Arab citizens into the tech workforce could be the key to improving relations. Under the banner of “Tech2Peace” Israeli entrepreneurs have sponsored two-week “High-Tech and peace-building seminars,” intended to foster cooperation and team-building among Jews and Palestinians. “I believe that technology can break walls between any two sides of the conflict because it's borderless,” one participant told the BBC. These efforts elide the fact that Israel’s most important tech innovations have been devised to surveil and control the Palestinian population, and that even Silicon Wadi’s biggest boosters attribute its success to the necessities of military occupation. Like Silicon Valley moguls who condemn Trump’s Muslim ban while building the technologies he uses to track immigrants and police the border, Israel’s tech leaders speak the language of humanitarianism while enabling inhumanity.

These insulting techno-fantasies reached their satiric zenith at an economic conference hosted by Jared Kushner in Bahrain last June. To an audience including Gulf State economic ministers, venture capitalists, former United Kingdom Prime Minister Tony Blair, and SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son, Kushner unveiled a $50 billion investment plan for the Palestinian territories to unlock its entrepreneurial potential. No Palestinians were in attendance save settler-friendly Hebron businessman Ashraf Jabari; no one mentioned the occupation or the blockade. US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin compared Gaza to “a hot IPO.”

At one point, Kushner played a video depicting a prosperous future for the West Bank and Gaza: as bright electronic music plays, trees rise from rubble, and drab, dusty streets turn green and vibrant; a desert in bloom. Overlaid text promises a transformed region, “modern cities,” and a “digital society.” Like the peace plan Kushner and Trump released in January (which many critics compared to a real estate deal), the striking thing about the Bahrain conference was not its content, but the brazenness of the pitch: forget diplomacy; think of the money we can make! In November, Vanity Fair’s Gabriel Sherman reported that the slick one-and-a-half-minute video Kusher played in Bahrain had been produced at the direction of a friend: Adam Neumann.

Everywhere, the powerful are dispensing with the sophistry and tender fictions they once used to solicit our consent. And still, a global order with fewer believable myths may not be meaningfully better than the one we inhabit now. As their authorizing narratives fray, states like the US and Israel will lean more heavily on brute force to maintain order and achieve their ends. But the failure of governments and corporations to fully colonize our imaginations, corrupt our symbols, and shape our desires is a cause for hope. As we hurtle toward economic collapse and a lethal contagion upends all certainty, words hollowed out and abandoned by the ruling class—peace, justice, community—are ours to reclaim. To repair the world, we must reinvest them with meaning.

Sam Adler-Bell is a freelance writer in Brooklyn, New York. He co-hosts the Dissent podcast Know Your Enemy.