AFTER MY FIRST LECTURE on the history of the Jews of Salonica at a Conservative synagogue near Princeton, a perfect stranger with a typical Ashkenazi surname sent me a package. In a handwritten letter, he expressed his appreciation for my “wonderful talk,” but concluded: “I hope that the Ashkenazi strands here can enrich the Sephardic side too.” That “here” referred to the book that accompanied the letter: Sander Gilman’s classic 1986 study, Jewish Self-Hatred: Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews. Did my first piece of fan mail insinuate that the history of the underrepresented Sephardic “side” was impoverished and could not stand on its own? Or that my de-emphasis of the Ashkenazi side amounted to self-hatred? I was so put off by the message surrounding the “gift,” that it took me years to crack the book open.

That piece of mail also reminded me why I pursued the academic study of Sephardic history in the first place: it was, in part, a form of self-defense. I wanted to arm myself with an understanding of the world from which my family came—my grandfather, whom I called nono in Ladino, was born in Salonica, once home to a major Jewish community in the Ottoman Empire and today the second-biggest city in Greece—and also to comprehend and combat the kind of sly prejudice I encountered in Jewish spaces. I had already grown accustomed to Jews—principally white, Ashkenazi Jews—using me as a screen on which to project their own discomfort and ignorance about Jews whose stories they do not know or cannot fathom. At a community-wide Holocaust commemoration in college, one of the organizers insinuated that I had made up the fact that my Salonican-born great-uncle and his family had perished in Auschwitz, since she was a survivor herself and had never met a Jew from Greece. In another instance, neighbors my own age, who are now rabbis in the Conservative and modern Orthodox movements, knocked on my door one Shabbat morning and asked if I would serve as their “shabbos goy”: “Because, you know, you’re Sephardic . . .” During one of my first visits to a Jewish research institution in New York, a senior colleague found out that my mother is Ashkenazi and retorted: “Aha! That explains your intellectual curiosity,” as if to say that if I were fully Sephardic, I would have no business engaging in scholarly pursuits.

Encounters since Trump’s election have involved more explicitly racialized language. A Jewish acquaintance, a baby boomer active in the Reform movement, recently learned of my family background and jokingly, or so it seemed, described “mixed breeds” like me with the derogatory term “mulattos.” A peer of my own generation invoked the “one-drop rule”—another “joke”—referencing the legal system in parts of the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries that disallowed anyone with a single black ancestor from “passing” as white in the eyes of the law. He referred to my son as an “octoroon,” a term used in slave societies to refer to those with one-eighth African and seven-eighths European ancestry.

Of course, these analogies are principally rhetorical. Like most Jews in America today, Sephardic Jews and their descendants most often operate as white (or at least provisionally white), which is perhaps why my friends and colleagues felt they had license to joke. And yet, the degrading intent of analogies to the African American experience offer clues to the architecture of Jew-on-Jew prejudice.

In fact, when I finally cracked Gilman’s Jewish Self-Hatred, I found it useful, but for reasons my fan could not have anticipated. Gilman is concerned with exploring “how Jews see the dominant society seeing them and how they project their anxiety about this manner of being seen onto other Jews [italics: mine] as a means of externalizing their own status anxiety.” Even though Gilman has nothing to say about Jews like me, with family roots in the Ottoman Empire, the psychological processes he describes can guide us through the multigenerational internalization and projection of anti-Jewish ideas among Jews themselves, powering a community obsession with dividing “good Jews” from “bad Jews,” “real Jews” from “fake Jews.” These classifications serve to show the non-Jewish world, and to prove to ourselves, that if the various antisemitic canards flung at us have a kernel of truth, they refer not to us, the good and real Jews, but rather, to them, the Other among us, the bad or fake Jews. We are legitimate and deserve to be accepted; they are illegitimate and deserve to be rejected.

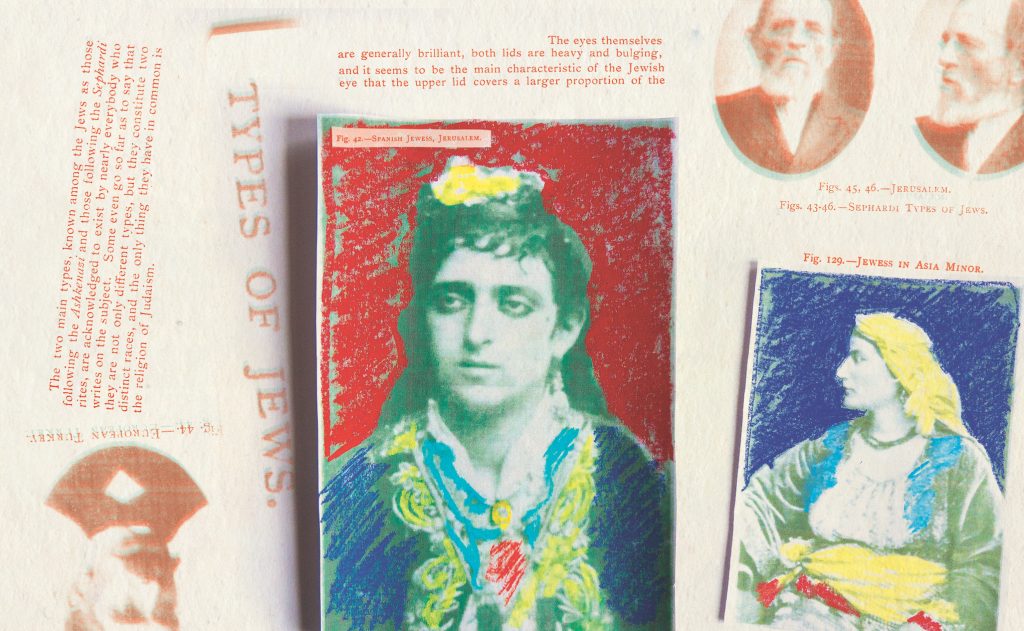

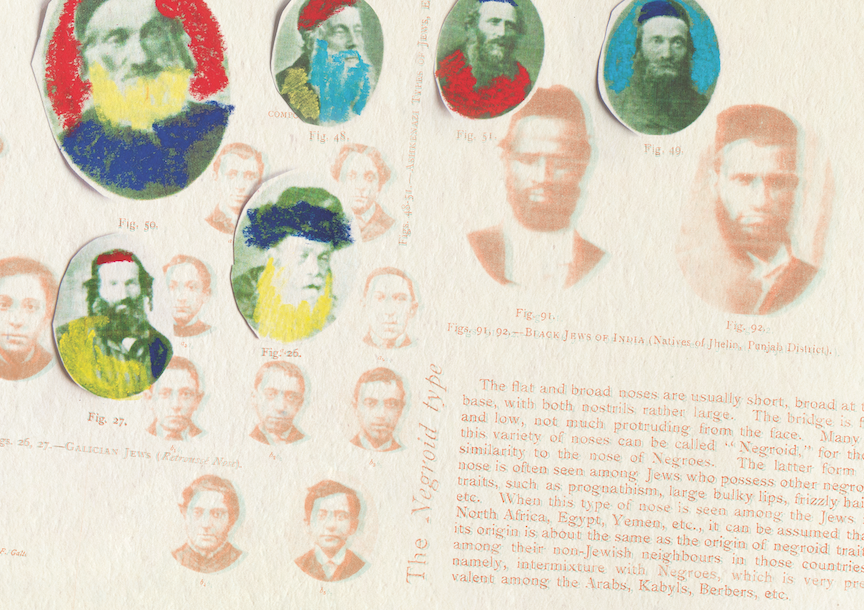

A close reading of the development of attitudes towards Sephardic Jews among Jews more generally provides an instructive example. The resulting dynamics will be all too familiar to Jews of color today, but also echo in the current treatment of Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews. Since antiquity, European Christian society has imagined “the Jew” as a principal Other: the murderer of the savior; the devil incarnate; horned, tailed, bearded like a goat, black in color—the antithesis of human. But the reality is that the Jew was one of several “Others” on the European mind. When Europeans disparaged Jews by analogizing them to two Others in particular, black people and Muslims/Arabs, they set off a chain reaction, whereby European Jews came to displace these comparisons onto the “fallen” or “fake” Sephardic Jews, subsumed by the Muslim world.

This pattern of intra-Jewish antagonism continued in the US, deepening with the adoption of American racial hierarchies. Today, it constitutes a structurally embedded dynamic of American Jewish life that imagines the fusion of Ashkenazi Jewishness and whiteness as the normative, predominant, and only legitimate way of being, acting, and representing “Jewish.” The assumptions are so banal as to be largely invisible—until they are explicitly invoked to police the boundaries of the “real” (i.e., Ashkenazi, white) Jewish community. By default, other forms of Jewish identity and practice are relegated to the margins as mere tokens or exoticized novelty sideshows (think one-liners about Sephardic Jews eating rice on Passover, which, by the way, is not universal among Sephardic communities), or are deleted from the conversation outright (as is generally the case for Jews of color).

Commentators and activists have identified part of the phenomenon as “Ashkenormativity.” But a nuanced exploration of the history reveals that we do not have an Ashkenormativity problem in the American Jewish community—or not only; like the country as a whole, we have a white supremacy problem. Grappling with the origin and depth of these roots can help us move beyond the insufficient concept of Ashkenormativity towards a broader understanding of the ways that we have been coerced into internalizing the primacy of whiteness, Europeanness, and Christianity to harm our own and others.

I. ANTISEMITISM, ORIENTALISM, AND ANTI-BLACK RACISM

The historic entanglements among antisemitism, orientalism, and anti-black racism reside at the heart of the European Enlightenment. None other than Immanuel Kant referred with disdain to Jews as “Palestinians in our midst,” capturing a dominant way of conceptualizing Jews as fundamentally alien, not only due to their religion, but due to their perceived origin beyond Europe, in the “Orient.”

The Jews were not only despised for their perceived Oriental nature, but also for their propinquity to black Africans. In Kant’s theologically infused vision of the world’s racial hierarchy, only white men were capable of realizing their full potential as rational, autonomous humans, actualizing the true spirit of Christianity that he saw as the bedrock of Western civilization. At the bottom of the racial hierarchy, he positioned “the Negroes of Africa,” whom he viewed, as a race, as “lazy, indolent and dawdling.” The Jews fell somewhere in between, but posed a greater threat than black people because of their status as aliens within Europe, which threatened to impede the realization of the white man’s full human potential. As a solution, he proposed the “euthanasia” of Judaism: its erasure through “reeducation” with “correct” culture.

Even the rhetoric of revolutionary movements of the 19th century did not escape the grip of orientalism and anti-black racism harnessed in service of antisemitism. In his letters to Friedrich Engels, for example, Karl Marx (the grandson of rabbis) repeatedly referred to his socialist adversary Ferdinand Lassalle (born Jewish) as a “Jewish nigger” as a way to debase his character and his ideas. Lassalle’s “pushiness,” Marx wrote, “is also nigger-like,” lending African origins to the “pushy Jew” stereotype. Engels, in turn, characterized Marx as “a dark from Trier,” whereas relatives nicknamed him “The Moor,” a denigrating reference to his complexion.

The British antisemite Houston Stewart Chamberlain added a more pseudoscientific gloss with his infamous Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899). Recasting Kant’s schema in the language of “race science,” Chamberlain argued that the “Aryan race” was superior to all others and viewed the contemporary Jew as a racially impure “half caste”; the ancient Israelites’ “admixture” with “Semites”—i.e., Arabs—and black Africans rendered modern Jews biologically inferior, “a transition stage between black and white.” Both inventive and despicable, Chamberlain garnered a wide readership among everyday people and major political figures—Hitler took direct inspiration from him and even attended his funeral.

But Chamberlain did something else remarkable: he distinguished between the “good” Sephardim, whom he idealized at a distance, from the “bad” Ashkenazim, whom he actually encountered in person and for whom he reserved his vitriol. Chamberlain projected the mystique of the original, Aryan essence of the Israelites onto the Spanish Jew: “genuine nobility of race . . . That out of the midst of such people prophets and psalmists could arise—that I understood at first glance, which I honestly confess that I had never succeeded in doing when I gazed, however carefully, on the many hundred young Jews—‘bochers’—of the Freidrichstrasse in Berlin.” Chamberlain solidified a dynamic of pitting “good Jews” against “bad Jews,” a dichotomy that, under pressure from dominant society, Jews themselves internalized and normalized to their detriment.

II. “REAL JEWS” AND “FAKE JEWS”

With the goal of securing their rights as citizens, European Jewish intellectuals—those bochers in Berlin—fought back by rejecting and deflecting the negative rhetoric directed at them. They did this in part by projecting it onto their own internal Others: the so-called Ostjuden, the Jews of Eastern Europe; and even more so, the Jews in “Muslim lands,” deemed the real Orientals among the Jews, the most uncivilized and inferior of all.

In his 11-volume History of the Jews (1853-1874), originally written in German, Heinrich Graetz composed a wildly popular grand narrative of Jewish history which would be translated into many languages and read for generations to come. He accepted the dominant idea that Jews were Oriental in origin, but, like Chamberlain, elevated the Jews of medieval Spain. It was thanks to the Spanish Jews that Judaism first assumed “a European character and deviated more and more from its Oriental form.” Graetz highlighted the 10th century scholar, physician, diplomat and patron of the sciences, Hasdai Ibn Shaprut, as one of the “first representatives of a Judaeo-European culture.” Graetz lifted up Ibn Shaprut’s work translating and preserving seminal texts of Western civilization that were otherwise lost during Europe’s Dark Ages as proof that Jews were not only “Europeans,” but more importantly, the saviors of European heritage and the “teachers of Europe.”

Notably, however, Graetz did not claim that all Jews had achieved the status of true Europeans. He expressed hostility toward Eastern European Jews, whom he demeaned as “Talmud-obsessed” and preoccupied with “hairsplitting judgment” that rendered them more narrow-minded than the intellectually versatile Jews of medieval Spain. Graetz further denigrated Yiddish as a “half-animal tongue.” His dehumanizing rhetoric was not so different from that employed by antisemites who imputed negative characteristics—narrow-mindedness, bigotry, and a lack of human language and culture—onto all European Jews.

As much as he belittled Eastern European Jews, Graetz further disparaged the descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. He referred to the majority, who settled in the Ottoman Empire, as “Turkish Jews” who “did not produce a single great genius who originated ideas to stimulate future ages, nor mark out a new thought for men of average intelligence. Not one of the leaders of the different congregations was above the level of mediocrity.” Read through an orientalist lens, the Turkish Jews sunk along with the Ottoman Empire, their glory “extinguished like a meteor and plunged into utter darkness.”

Worst of all, from Graetz’s perspective, was the conversion of some Turkish Jews to Islam in the 17th century—followers of the messianic figure of Izmir, Sabbatai Sevi. Graetz described Sevi’s followers as “the lowest savages,” “childish” “madmen” overcome by “mental disease” and “irrationality.” How else to explain their choice to abandon Judaism and embrace the backward religion of Islam? The Sabbatean movement, according to Graetz, threw “the whole Jewish race into a turmoil” that “long interfered with its progress.” Held responsible for such ignominy, Jews in the “land of the crescent” subsequently disappeared from Graetz’s narrative, only to reappear briefly as “Asiatic Jews” more than 150 years later—the helpless victims of the infamous blood libel in Damascus in 1840. The linguistic slippage—from “Spanish” to “Turkish” to “Asiatic”—solidified the image of the decline and disappearance of the Sephardic Jews from the Eurocentric vision of Jewish history and their submersion into the Islamic Orient.

For their part, Eastern European Jews rebelled against the image of themselves promoted by German Jews and developed a self-image as the “real” Jews, who resisted the yoke of assimilation. Philosopher Martin Buber notably reclaimed the Eastern European Jew as the embodiment of authentic Jewishness manifest in the creative spirituality of Hasidism. The Yiddish language was recast from a “half-animal tongue” into the source of the Jewish spirit, binding Jews together as a nation. Non-Yiddish-speaking Jews, alas, were excised from this national conception.

A similar style of denigrating rhetoric, used by antisemites to demean Jews and by German Jews to distance themselves from the so-called Ostjuden, was also projected by the Eastern European Jews onto the Jew further to the east, beyond Europe, in the Muslim world, where the truly “bad” Jews resided. In the period between the world wars, Simon Dubnow, a Jewish historian and proponent of Jewish cultural autonomy in Russia, mocked the “hybrid” Jews of Salonica and Istanbul, whom he viewed as lacking a sense of Jewish nationhood. Lured by assimilation, he argued, they failed to become either true Europeans or Turks and instead were reduced to a “superficial cosmopolitanism of the Levantine type.” (“Levantine” referred not only to the geography of the eastern Mediterranean, but also, pejoratively, to the impurity and rootlessness of those who inhabited the region.) Dubnow alleged that only the arrival of a small cohort of Ashkenazim to the Ottoman Empire had introduced “diversity and liveliness to the congealed Sephardic culture.”

The orientalist rhetoric intensified in the realm of Zionist thought in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The founder of political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, claimed that in building up European Jewish presence in Palestine, “for Europe we will constitute a bulwark against Asia, serving as guardians of culture against barbarism.” Full regeneration of the Jew in Palestine, Herzl indicated in his famous novel Altneuland, would result in the creation of a “Europe in the Middle East.”

A well-known Zionist and the founder of the sociology department at Hebrew University, Arthur Ruppin, added an elaborate racialized gloss to the orientalist rhetoric of Zionism. Influenced by social Darwinism, he internalized the racist thinking of the era to recast the Eastern European Jew as the Urjude, the original Jew for whom and by whom the new Jewish state in Palestine ought to be built. According to Ruppin, if the Semitic and Oriental racial categories, as described by Chamberlain and other antisemites, related to language, then Eastern European Jews could not be classified as such because they spoke Yiddish—a Germanic language. Ashkenazim, not Sephardim, thus preserved the “Indo-Germanic” and “Aryan” racial composition of the original Israelites. The problem, as Ruppin imagined it, was that as a result of contact with Semites—especially Orientalized Jews and Bedouins—the racial stock of Ashkenazi Jews had deteriorated. Only on their own land could their race be regenerated and preserved in the face of harmful “dysgenic” influences from the Oriental, Semitic Arab—influences that had already drained the “life force” out of those descendants of Spanish Jews in Palestine who had “assimilated” to the Arab way of life and had become “poorly educated” and of low “moral standing.” Ruppin lumped the descendants of Spanish Jews together with the “Jews of Morocco, Persia and the Yemen, who have come into Palestine of recent years,” thereby solidifying the broad category of “Sephardim,” all of whom he viewed as equally “degenerate.”

Based on little evidence, Ruppin attributed the diverging “racial health” of Sephardim and Ashkenazim to their differing “breeding” habits: Ashkenazim married their daughters to sages. Meanwhile, Sephardim, due to their Oriental essence, which stripped them of their instinct for self-selection, did not reproduce with strategic intention. According to Ruppin, this explained Ashkenazi distinction:

Ashkenazi Jews in our time are better than Sephardic Jews in their abilities and their inclination to sciences. In the schools of Eretz Israel, in which the children of Israel from all over the world study together, the superior ability of the children of the Ashkenazi Jews is a well-known fact.

Such breeding habits also explained, for Ruppin, why Ashkenazi Jews had become so numerous whereas Sephardic Jews had decreased in number. He concluded with a definitive pronouncement on who constituted the “real” Jews: “The Ashkenazim today form such an overwhelming majority among the Jews that they are in many cases even considered ‘the Jews’ par excellence.”

III. THE LIMITS OF THE AMERICAN MELTING POT

For those familiar with the history of Zionism and the experiences of Mizrahim in the state of Israel, this kind of rhetoric and the policies that derived from it—such as the Israeli state’s segregation of Mizrahi Jews into poorly served “refugee absorption camps,” and the kidnapping of Yemenite and other Mizrahi and Sephardi children to give to childless Holocaust survivors—will not be surprising. What may be more surprising is how similar racist rhetoric along the Ashkenazi-Sephardi divide played out in the United States.

Jews often imagine the United States as an exceptional country, one which did away with old- world animosities and where Jews have thrived like nowhere else (besides, perhaps, medieval Spain or pre-war Germany). Indeed, George Washington’s famous letter to the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1790, characterized the government of the United States as one that “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance,” where “every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be no one to make him afraid.”

But Washington owned slaves, as did the founder of the Touro synagogue, Aaron Lopez. The inclusion of European Jews in Washington’s imagined world of American tolerance only extended to different faith groups among whites and was contingent upon Jews’ complicity in perpetuating anti-black (and anti-indigenous) racism. The same year that Washington expressed his “toleration” for Newport’s Jews, Congress made its first declaration concerning the eligibility of a foreigner to become a naturalized US citizen. The only requirement was for the petitioner to be a “white person.” Mixed-race, Native American, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and a wide variety of other peoples were thus excluded from US citizenship from 1790 until racial prerequisites were abolished in 1952 (those of “African descent” became eligible after the Civil War); Jews were never denied petitions for naturalization based on race, even if they experienced antisemitism in many other contexts.

As the era of racial pseudoscience emerged in the 19th century, Jews posed a quandary for American intellectuals and politicians. As a way to safeguard their inclusion in the favored caste, Jewish leaders advocated for the expansion of the boundaries of whiteness to include not only those from Western European Protestant countries, but rather from all of Europe. In his famous play The Melting Pot (1908), Israel Zangwill articulated his vision of America, where “all the races of Europe [emphasis: mine] are melting and reforming . . . Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and Englishmen, Jews and Russians—into the Crucible with you all! God is making the American.” Notably, Zangwill omitted all non-Europeans: Asians, Africans, Latinxs, indigenous peoples. In short, whites only, inclusive of European Jews.

When the privileges that European Jews had attained in the United States appeared to be threatened, their leaders mobilized in defense. When the case of a (Christian) Syrian who sought to be naturalized came before a US court in 1909, Jewish leaders panicked: if Syrians were deemed “Asiatic” or “Mongoloid” and thus ineligible for naturalization, perhaps white-looking Jews—perceived at the time to be racially “Semitic” and classified by US immigration authorities as “Hebrews” by race into the 1940s—would lose their right to citizenship. The judge in the case indicated that while he would permit European Jews to be naturalized because he viewed them as “racially, physiologically, and psychologically” European, by the same logic, Syrian Jews should be classified differently: “Asiatics” ineligible for naturalization.

As the racial status of Syrians continued to be debated—the courts ultimately deemed them, and all Middle Easterners, “white”—Sephardic Jews began arriving in the United States from the Ottoman Empire, and American Jewish leaders opined over their new “problem” of “Oriental immigration.” At a meeting of the National Conference of Jewish Charities in 1913, documented in its published proceedings, Maurice Hexter, who later became vice president of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies in New York, mimicked the rhetoric of the judge in the Syrian naturalization case, arguing that Oriental Jews ought to be treated in a manner completely differently from “our” Jews—the already established “European” Jews. So great was “the psychic and psychological difference,” Hexter emphasized, between the “Levantine Jew” and his European coreligionists that “there seems to be little in common.” Another commentator disparagingly insisted: “The Levantine Jew is as human, or almost as human, as any other.”

America was no stranger to intra-Jewish tensions—the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, established in the Americas since colonial times, drew upon the Sephardic mystique to fashion themselves as the “grandees,” American Jewish nobility, while the uptown German Jews in New York looked down on the downtown Eastern European Yiddish speakers with disdain. But this was the first time that American Jews denied other Jews’ claim to Jewishness, as German and especially Yiddish-speaking Jews did in distancing themselves from the newcomers from the Ottoman Empire.

As recounted by historian Aviva Ben-Ur in her book, Sephardic Jews in America, Ottoman Jews went to great lengths to prove themselves to other Jews, revealing their talletoth and tefillin, the Hebrew-lettering of their Ladino newspapers, and in some instances, their circumcisions, often only to be rejected as impostors—Muslims or Turks, Italians or Puerto Ricans, but certainly not Jews. Under the leadership of Judah Magnes—the Reform rabbi who later advocated for a bi-national Jewish-Arab state in Palestine—the Kehillah, New York’s main Jewish communal organization at the time, rejected requests from Levantine Jews for assistance for their own communal organization and Ladino newspaper. The Hebrew Immigrant and Aid Society (HIAS), which helped thousands of Jews navigate immigration regulations, only reluctantly took on the cases of Levantine Jews in the early decades of the 20th century; the organization’s director thought the newcomers ought to instead settle in Cuba, where he believed they would be more likely to succeed in the slow-paced society and warmer climate. The Immigrant Removal Office, which helped resettle Jews across the country, refused to publish its guidebook in Judeo-Spanish despite requests and despite publishing editions in other languages. The exclusion of Levantine Jews from American Jewish institutions was nearly complete.

IV. STUDYING THE “BACKWARD” LEVANTINE JEW

Seeking to determine the social welfare needs of Jews in New York, in 1926 the Bureau of Jewish Social Research commissioned a well-known economic historian, Louis Hacker, who later served as a dean at Columbia University, to study the conditions impacting the city’s Oriental Jews. An equivocal act of inclusion, the first “academic” study of Sephardic Jews in the United States provocatively began by claiming that Ottoman-born Jews were “almost as alien to their [Ashkenazi] kinsmen as are the negroes to the average white Southerner.” Echoing the anti-black and orientalist rhetoric that Kant and Chamberlain harnessed in the service of antisemitism, Hacker now projected similar characteristics onto the Levantine Jews. He attributed the challenges they faced to their racial inferiority, which he viewed as stemming from the “backward,” “Mohammedan” atmosphere of their birth; he feared they would not be able to “slough off” such racial differences. By likening them to the “Negro” within; the invading “Oriental” from without; and the menacing “Mohammedan” from afar, Hacker relegated Levantine Jews to the furthest margins of American Jewish life and to the bottom of the racial hierarchy.

The only hope for salvation that Hacker saw for the backwards Ottoman Jews was if they spent more time with “our” Jews, the Ashkenazim, who could teach the newcomers how to be white, civilized, Euro-Americans. Appealing to eugenics, Hacker hoped the Levantine Jews would “interbreed” with the Ashkenazim so that the stain of their “Negro”- and Muslim-like status would eventually, over a few generations, be either unlearnt or bred out of them. But even here, Hacker equivocated, fearing that the Levantine Jews’ “Oriental temperament” encouraged “localism” and “clannishness,” which impeded their ability to integrate into the Jewish community. Due to the Levantine Jews’ “inherent characteristics,” Hacker concluded that the Jewish establishment could not do much to help the newcomers.

Just as Graetz and Ruppin refracted and deflected the pervasive anti-Jewish rhetoric in the European context, so, too, did Hacker in the United States. As he was preparing his study, New York tabloids were running sensational articles about the inferior racial stock of the Jews, their desire for power, and the threat they posed to American society, while touting Congress’ decision to limit Jewish immigration through the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924. These anti-Jewish screeds, including “The Pedigree of Judah” (1926) by infamous eugenicist and Klansman Lothrop Stoddard, echoed Chamberlain’s claim that Eastern European Jews were not “real” Jews, but rather descendants of Tatars and Asiatic tribes: “like gispies [sic] in everything but in name.” North Carolina’s first Poet Laureate, scholar and theologian Arthur Abernethy’s bestselling 1910 book, The Jew A Negro gained further traction when serialized in the 1920s:

The Jew of today is essentially Negro in habit, physical peculiarities and tendencies . . . Like the Negroes the Jews have no country; like the Negroes, their whole history shows they were never capable of self-government without direct assistance from God; like the Negroes they have foisted race riots on countries where they have lived . . . The overshadowing predominance of the Negro question has alone kept the American people at peace with the Hebrew. When—and the day is closer at hand than we imagine—the Negro is eliminated from the citizenship of the United States . . . the American government will turn its attention to the alien Hebrew.

The Jewish Daily Forward, the most prominent Yiddish newspaper at the time, rebutted these defaming articles. That encounter with antisemitic rhetoric provides the backdrop for understanding how The Forward treated Hacker’s report on the status of “Turkish Jews” in New York. Reflecting the orientalist perspectives and racist thinking of the day, Nathaniel Zalowitz, the editor of the English section of The Forward, decreed:

In the ‘old country’ they [Turkish Jews] had no cultural life of their own worth speaking of. They had no common body of customs and traditions, no common literature, no knowledge of or curiosity about their past. They had not been revived by a great spiritual movement such as Chasidism which rescued the Jews of Eastern Europe from stagnancy. They had been a backward people in a backward country, and how could they hope to progress in this country?

As antisemites had denigrated Jews for lacking the ability to create culture—the German composer Richard Wagner (Chamberlain’s father-in-law) did so most infamously in his 1850 essay, “Jewishness and Music”—so the premier newspaper of Eastern European Jews in New York denied the same human capacity to Levantine Jews. Replicating the language of antisemites like Stoddard the Klansman, in another essay in The Forward, Zalowitz lamented that the Sephardic Jews had become nothing but a “horde of gypsies.” Appeals to this kind of rhetoric enabled one segment of Jews to self-whiten by rhetorically blackening another segment.

Levantine Jewish leaders in New York expressed outrage over Hacker’s report and The Forward’s reportage, as revealed in a cache of previously unstudied documents at the American Sephardi Federation in New York. An intellectual from Salonica, Henry Besso, wrote lengthy letters to Hacker and The Forward refuting each exposé and requesting that a Sephardic view of their own situation be published. Hacker responded by insisting that his study was “impartial in every sense” and that The Forward sensationalized it. But a review of Hacker’s longer, unpublished manuscript reveals that he clung to his presuppositions despite empirical evidence that proved otherwise. For example, Hacker argued that while the Levantine Jew can speak many languages, “he cannot, as a rule, read them.” His data, however, showed that the vast majority of Levantine Jews—83% of those he interviewed—read Jewish periodicals on a weekly basis (not to mention other non-Jewish publications). He never published this particular finding, instead burying the statistic in an unpublished appendix.

Zalowitz, too, passed the buck: “My motive was an honorable one. I had no intention to write a sensational article. I was merely interested in familiarizing our Ashkenazic Jews with the Sephardim. Hence, your quarrel is not with me, but with Mr. Hacker.” Zalowitz indicated that a “pro-Sephardic” article might be appropriate for his newspaper at some point, but said that Besso’s letter could not be published because of its “European English.” No article by a Sephardic Jew expressing their “side” of the story appeared in the newspaper. In addition to being denigrated, they were effectively silenced.

V. “LET ME ENTER . . .”

Hacker’s read on the status of Levantine Jews in America persisted essentially unchallenged for decades. Through the 1970s, Besso and his friends lamented the irrevocable damage done by the “Hacker Report” and bemoaned the extent to which the Jewish establishment continued to ignore, marginalize, or erase Sephardic Jews.

But something equally disturbing took place as the cycle of internalizing prejudice continued, leading some Levantine Jews to accept central aspects of Hacker’s assessment. One such figure was a colleague of Besso’s, the Dardanelles-born professor Maír José Benardete who played an instrumental role in establishing the first Sephardic Studies program at an American university—at Columbia in the 1930s, notably under the aegis of the Hispanic Institute, and unconnected to the chair of Jewish history held by the famed scholar Salo Baron. In his magnum opus, eventually published in 1952 as The Hispanic Culture and Character of the Sephardic Jews, Benardete praised Hacker’s report for transmitting “indisputable” facts. Benardete agreed with Hacker’s assessment that Levantine Jews suffered from “localism” and “clannishness,” but merely disagreed about the origin of such behavior, which he attributed not to their backwards “Oriental homelands” but rather to their “noble” Spanish “formation,” which preserved the original tribal instincts of the “Palestinian beginnings of the Jews.”

Our story has essentially come full circle: As a mode of self-defense, Benardete appealed to the myth of Sephardic superiority, internalizing the rhetoric of antisemites like Chamberlain, and asserting that the Sephardic Jews—including Levantine Jews—should be recognized as the most authentic Jews. “Where Mr. Hacker says Oriental, substitute the word Spanish, and the characterization is most apt,” he wrote. Such a terminological shift enabled Benardete to reposition his generation of Ottoman-born Jews as heirs to the glory of medieval Spanish Jewish culture, to recast Ottoman and Oriental Jews as Spanish—European, and ultimately white. The reclamation of the term “Sephardic” in the American context deleted the purported stain of more than four centuries of life after 1492 in the Islamic Orient, reversing the linguistic lurch from “Spanish” to “Turkish” to “Asiatic,” and rendering those Jews who claimed the title more legible and legitimate to the white, Ashkenazi Jewish establishment.

But Levantine Jews have been only partially successful in rehabilitating their image and legitimizing their experience, including in the United States. Scholarship in the field of American Jewish history still draws upon Hacker, whose perspective continues to reverberate generations later. The single paragraph about Levantine Jews in historian Hasia Diner’s acclaimed 447-page volume The Jews of the United States, 1654-2000 emphasizes the “deep divisions” among them (seemingly a result of their “clannishness”) and cites a single source from 1973: an article by acclaimed Sephardic rabbi and scholar Marc Angel. Angel indicates that his model and inspiration was Benardete’s book (acknowledged in the second footnote), while also drawing extensively on Hacker’s foundational report—cited 10 times without critique. The chain of footnotes reveals that deeply rooted, racially charged ways of thinking have not been overturned, but rather internalized and sublimated so completely as to become invisible.

The irony is that “Sephardic Jews” do play an important role in the American Jewish story as it is still told today: The Spanish and Portuguese Jews who arrived in New Amsterdam (today’s New York) in 1654 are credited with initiating Jewish presence in North America. But these were the “good” Sephardic Jews, the ones who enable us to claim that we Jews are not foreign to the United States, but have been here since “the beginning” (which, it should be said, deeply implicates us in the colonial conquest of the continent). Thus begins the story of Jewish “contributions” to our country, accomplished by synthesizing our Americanness and Jewishness. The Levantine Jews, those “Oriental” Sephardic Jews, cannot be used to advance that kind of triumphalist American Jewish story. To the contrary, Levantine Jews are the “bad” Sephardic Jews, who pose a problem to the idealized Jewish narrative by exposing the less European, less white elements of the experience. More fundamentally, they force us to confront the inconvenient truth of deep-seated intra-Jewish prejudice.

There is a Ladino refran, or proverb, that goes: Deshame entrar, me azere lugar (“Let me enter and I will make a place for myself”). I used to think that Sephardic Jews—like many “other” Jews—just needed to have the door opened by the gatekeepers, especially the white Ashkenazi Jewish establishment, in order for their fate to improve. In fact, I owe my study of Sephardic history to one such professor, who opened the door for me early on, encouraging me on my path even as others tried to dissuade me. For that I remain forever grateful.

But a seat at the table is not enough for today’s generation. Sephardic identity and culture have largely been swallowed up by Ashkenaziness, by whiteness, by erasures so complete that many of my peers no longer possess a consciousness of what it could mean to be Sephardic today. Those sublimated histories must be reclaimed and those submerged stories raised up. Resources from the American Jewish establishment—universities, synagogues, federations, media outlets—must be allocated to recuperate those cultural, linguistic, and religious legacies that have been marginalized, as a step toward a broader goal: the decolonization of American Jewish life.

The process begins by acknowledging the multigenerational toll exacted by exclusionary practices foisted onto our communities from without, and absorbed and weaponized within. Figures discussed here—Graetz, Ruppin, Hacker, Zalowitz, Benardete—dedicated tremendous effort to securing their own status within racial, cultural, and civilizational hierarchies that privileged whiteness, Europeanness, and Christianity (to say nothing of masculinity, heteronormativity, and ruling-class interests). They deployed these harmful tactics out of a deeply felt vulnerability, and a failure to fathom any option for survival other than to maneuver within the system—a system established and perpetuated by none other than their enemies, the likes of Kant, Chamberlain, Stoddard, and Abernethy.

That unjust system has not gone away. It continues to thrive on horizontal oppression perpetrated by vulnerable communities pitted one against the other. It is easier to step on your relatively powerless brother or sister than to dismantle systems of racism and exclusion. And yet, there is no other way, for as long as these prejudices exist, Jews will be implicated in them. Confronting the deep-seated and disturbing history of intra-Jewish prejudice is a prerequisite for the empowerment of Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews—and Jews of color—in Jewish spaces, and for a reckoning with the place of most Jews as targets of, and willing and unwilling accomplices to, the structures of white supremacy. Only a Jewish commitment to dismantling white supremacy will do justice to our own histories, keep our own communities safe, and fashion new foundations upon which to rebuild American—and American Jewish—society.

Author’s notes: I am grateful to many scholars whose work has informed this piece including Aviva Ben-Ur, Etan Bloom, J. Kameron Carter, John Efron, Eric Goldstein, Sarah Gualtieri, Aziza Khazzoom, Ian Haney López, Derek Penslar, Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, Aron Rodrigue, Ismar Schorsch, Daniel Schroeter, and Ella Shohat.

In memory of one of my first mentors and advocates, Henry W. Berger (1937-2018)

Devin E. Naar is an associate professor of Jewish studies, Sephardic studies, history, and international studies at the University of Washington in Seattle and the author of Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece.