Memories of A Here-and-Now Place

The end of old Jewish Miami Beach and the rise of Little Haiti, 1977–1986

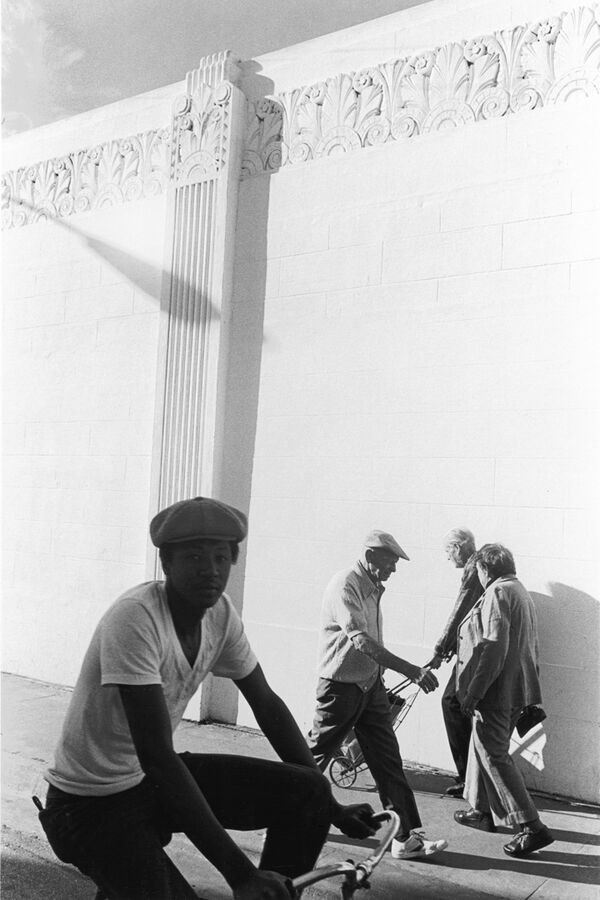

It was a clear, spring morning in 1980, and it found me as I often was at that time: wandering around the Miami neighborhood of South Beach with my Leica strapped to my wrist, photographing the elderly Jewish people who made their lives there. I raised the camera as three of them were walking by, running their morning errands. I was about to depress the shutter release button when a young Haitian man on a bicycle glided into the frame; I instinctively snapped the photo and continued on my way. A few days later, as I looked through that week’s crop of prints, it struck me that I’d been photographing the end of one era and the beginning of another: One community had run its course in this derelict strip of beachfront paradise, and a new group of immigrants was now beginning its story. I was seeing two cultures in one frame, at opposite ends of distinct strands of migration to Miami Beach.

Young man on bicycle, South Beach, 1980, 35mm film

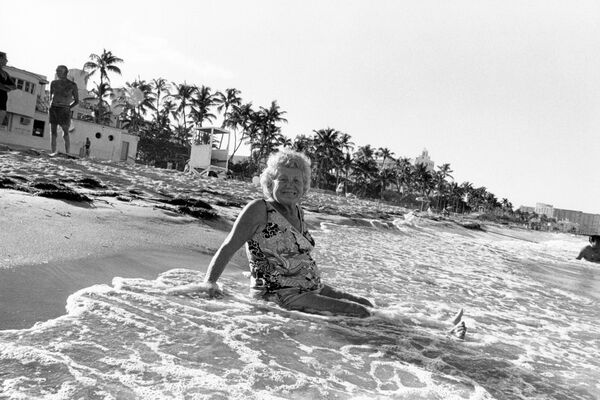

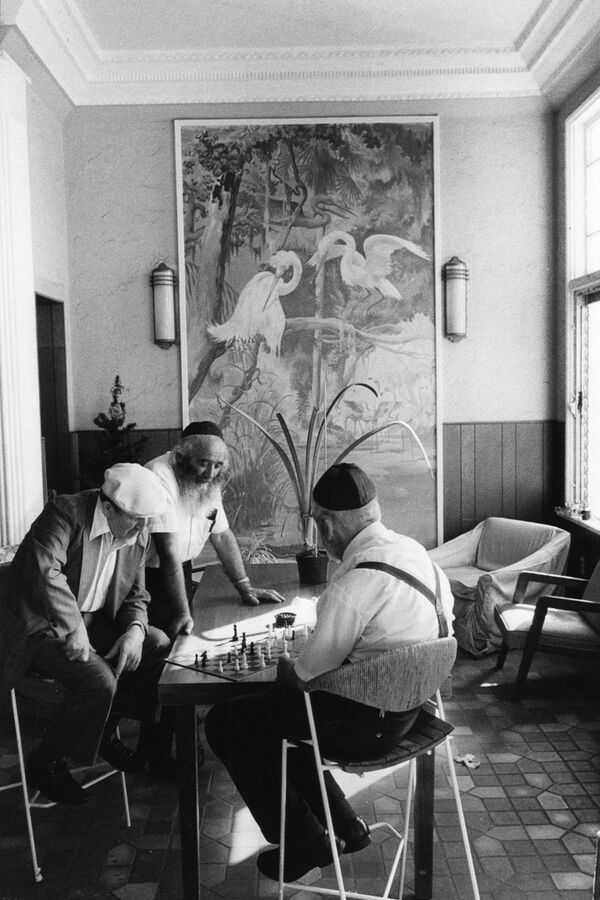

From the 1950s through the ’80s, South Beach was a refuge for elderly Jewish retirees, who found solace in the subtropical climate and community in the shtetl-like neighborhood. These men and women were of an Eastern European lineage whose roots extended back to the tsarist pogroms and Nazi Germany. Their families found safe harbor at Ellis Island and made their homes in New York City before settling in South Beach—which was, for many of them, literally and figuratively, a last resort. The South Beach they inhabited was a last bastion of an Ashkenazi communal life now iconic in the American imagination. All along Ocean Drive, day and night, old people sat out on their hotel porches. Women were not permitted to light Shabbat candles in their rooms, so on Friday evenings, it was common to see a tray of paired burning candles in the lobbies. Card rooms and social halls were often converted into makeshift shuls, the Torahs brought out of their arks on Mondays and Thursdays. Dances were held Saturday nights at the Tenth Street Auditorium and each week there was round dancing at Pier Park. Exercise groups met regularly in Lummus Park, the popular, mile-long grassy space between Ocean Drive and the beach. Musicians from the neighborhood performed there, too. Around election time, politicians came to the park to campaign among these residents, who cherished casting ballots; the candidates would kibitz and sing in Yiddish—a common language—and hand out Dixie cups of vanilla ice cream.

My mother and father left Brooklyn during World War II—changing the family surname from Musikoff to Monroe to avoid antisemitism—and, in the late 1940s, they landed in Miami Beach. By the time I was born in 1951, my father made enough money to move to a wealthier neighborhood, but we stayed nevertheless; perhaps, with its small apartment buildings and walkable lifestyle, South Beach reminded my parents of Brooklyn. In 1975, I moved to Boulder, Colorado, to get my MFA in photography. Leaving made me realize the specialness of the place I’d grown up, and after graduation, I hurried home with the singular intention of photographing what I realized was a precious legacy: the lifestyles of the old-world Jewry I’d grown up with.

Woman at shoreline, South Beach, 1978, 35mm film

People sitting on the Essex House hotel porch, South Beach, 1979, 35mm film

Men playing chess by an Earl LaPan mural in the Arlington Hotel, South Beach, 1978, 35mm film

Things changed in 1980. Over five months, beginning in April, the Mariel boatlift—a mass emigration granted by Cuban President Fidel Castro and organized by Cuban Americans—brought 125,000 Cuban exiles to South Florida. By that point, Jewish South Beach was already in economic decline: The buildings were run-down; the old were beginning to die; the tourists had long ceased to visit. Hoping to attract new money for revitalization projects, the City of Miami Beach had placed a building moratorium on South Beach, which hastened blight and lowered property values. The new Cuban immigrants flocked to where the rents were cheapest—and they were largely met with hostility. The “Marielitos” arrived to Florida amid a growing anti-immigrant wave that had gained momentum in the context of mass migration from Southeast Asia to the United States in the years prior; and spectacular reports that Castro had “emptied the prisons” onto the boats leaving from Cuba’s Mariel harbor stoked fears surrounding the new arrivals. Newspapers readily amplified crime stories, which included events related to the intensifying cocaine trade—a violent economy that financed the luxury real estate development that defines contemporary South Florida. Afraid of leaving their apartments while it was still dark, the elderly Jewish residents of South Beach abruptly ended their sunrise swims.

Swimmers at sunrise, South Beach, 1979, 35mm film

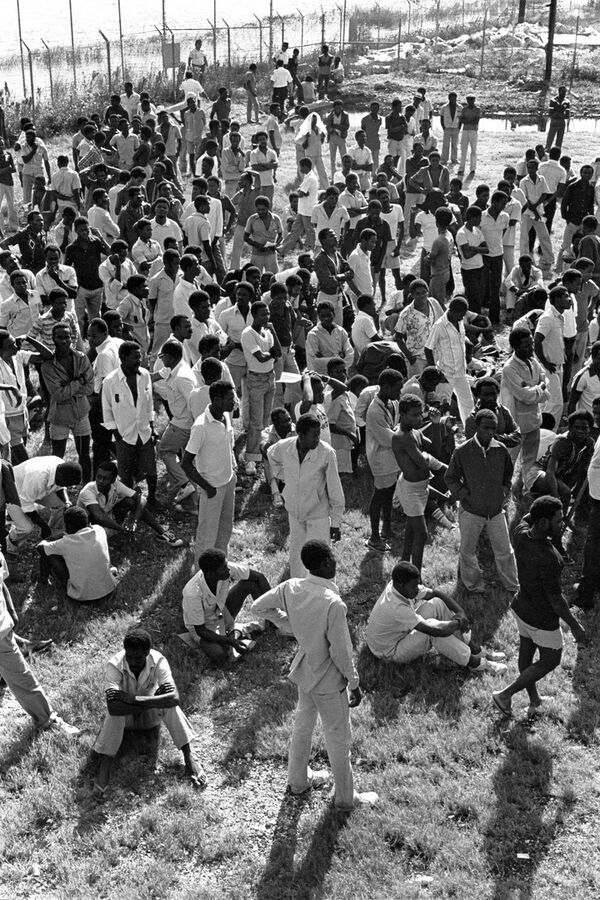

Marielitos at Tent City, 1980, 35mm film

That year also saw the migration of around 20,000 Haitians. Since 1972, Haitians had been arriving in the US in large numbers in an attempt to flee the devastation wrought by Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s repressive regime. Since the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966, most Cubans living in the US qualified for asylum and permanent residency; Haitian refugees, however, were dubbed “economic migrants” and regularly detained and expelled. As tens of thousands of migrants landed on Florida’s shores, President Carter created a new immigration category, “entrant”—which kept both Cuban and Haitian arrivants in legal limbo, as their asylum claims were decided case by case. But in 1984, President Reagan’s administration once again declared “Marielitos” eligible for permanent residency under the Cuban Adjustment Act; Haitian entrants, meanwhile, had to wait another two years to become eligible to apply for general amnesty. Subject to legal and extralegal anti-Black racism, Haitians faced massively constrained economic opportunities, as well as significantly higher rates of deportation and detention.

Reading about the influx of Haitian refugees spurred my curiosity. In 1981, I drove to the now-infamous Krome Avenue Detention Center, where, at its most crowded, nearly 1,500 Haitians were housed in a complex meant for 869. When I reached the facility at the western edge of Miami, where it begins to give way to the Everglades, I was turned away by a guard. Eventually, I got a meeting with Cecilio Ruiz, the officer-in-charge. Media access to Krome was highly restricted at the time, but as I recall, I expressed my intentions to take photographs at the facility and showed Ruiz a box of my South Beach work. To my surprise, he said he’d have a coveted “No Escort Required” badge left at the front desk for me, insisting he had nothing to hide.

I went to Krome a couple of afternoons weekly for nearly a year. Though there was a pretense of organized activity at the facility—soccer games, arts and crafts, Catholic services—I think the detainment would be best described as a communal lingering. Though it is an understatement to say that the conditions of photographing the two populations differed significantly, when I photographed at Krome I tried to preserve the ethos I had developed in observing the elderly Jews of South Beach: Using a small, handheld camera, I made myself scarce, awaiting fleeting bursts of life. As in South Beach, I sought to capture the organic textures of daily life expressed most clearly when people are not burdened with the self-conscious feeling of being watched. In Krome, people mostly ignored me as I flowed around the camp.

Women being photographed during intake processing, Krome Resettlement Camp, 1981, 35mm film

Detainees by Woman’s Building, Krome Resettlement Camp, 1981, 35mm film

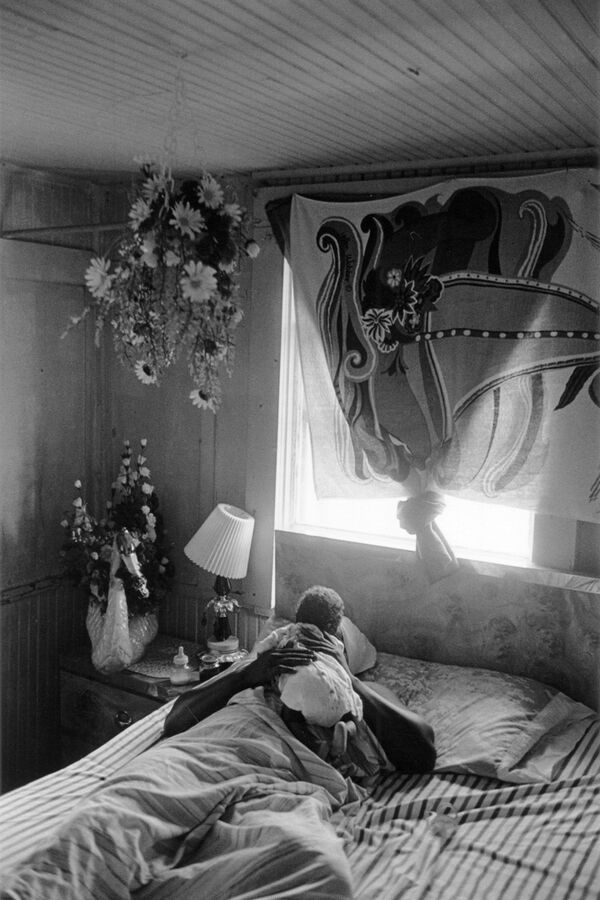

Seeking to more fully engage with this community whose presence was newly felt in the area where I grew up, I ventured into Miami’s Little Haiti, off limits to “blans” by self-imposition. Discrimination against the community was rampant: Many blamed Haitians for bringing AIDS to Miami. I walked the quiet streets over and over, photographing along the way. The best images were those made without plan or agenda. I barely know how I found my way into people’s homes, photographing young men dressing in a bedroom or a mother and baby lying lovingly in their bed. I stumbled into classes off the old hallways of Notre Dame D’Haiti Church where new immigrants were learning English. Not all of the spontaneous moments were quiet ones: Upon hearing that “Baby Doc” fled Haiti amid a popular uprising in 1986, I raced to Little Haiti to photograph the ebullient celebrations in glowing, tropical morning light.

Detainees by Woman’s Building, Krome Resettlement Camp, 1981, 35mm film

Woman with baby in apartment, Little Haiti, 1982, 35mm film

Untitled, Little Haiti, 1985, 35mm film

Celebrations on the morning of “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s departing Haiti, Little Haiti, 1986, 35mm film

Even as I made time to observe Little Haiti come to life, I was dedicated to my South Beach work, drawn as ever to the neighborhood’s frenetic visual field. Still, I did not care for what South Beach was becoming. As the decade progressed, South Beach began to “improve,” unraveling the old-world community of my youth. Miami Vice, which cast the city’s violence in a steamy, sexy light, aired in 1984. The Miami Design Preservation League painted the hotel facades along Ocean Drive in pastel hues, and the strip made for terrific backdrops for the action-packed show. Glamour was returning to South Beach. Fashion models came en masse, parading along Lincoln Road during their breaks from work. Clothing boutiques, fine restaurants, and flashy nightclubs proliferated. Meanwhile, it became less and less common to see the neighborhood’s old residents shopping along Washington Avenue; their Judaica shops, jewelry stores, and beauty parlors vanished. My own personal barometer for the vitality of South Beach Jewry was its New Year’s Eve parties, which I photographed each year, hopping from one to the next, from 1977 to 1986. The revelers had a proverbial foot in the grave yet greeted every new year with joy and optimism, dancing and celebrating at the hotels along Ocean Drive and Collins Avenue—and mostly wrapping up before the ball dropped in Times Square. By 1985 the parties were fewer and less jovial. By 1987, the handful that remained were too lackluster for me to photograph. It was all over.

New Year’s Eve hotel party, South Beach, 1978, 35mm film

The old South Beach days are long gone. No longer is there a pushke in every home or a mezuzah on each doorjamb. Few signs remain of the elderly Jewish people who claimed South Beach as the place to live in accordance with their religious values and communal mores. Little Haiti, on the northern side of the ever-popular Wynwood and Miami’s design district, is on high ground, a developer’s dream now. Gentrification will likely prevail there, too, pushing another vibrant community to the margins to make way for the young, restless, and wealthy. Despite climate change and rising sea levels, there is a new skyline of dizzying skyscrapers shimmering in the blue light of sea and sky, obscuring the hardships that thwart the realization of the American Dream. I feel as though I’ve watched many versions of communal life vanish in Miami. The city has a short memory; it’s a here-and-now place.

Gary Monroe, a native of Miami Beach, earned an MFA from the University of Colorado at Boulder in 1977. He then returned home to spend a decade photographing the disappearing old-world Jewish community that defined South Beach. His life’s work is archived at Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.