Responsa is an editorial column written by members of the Jewish Currents staff and reflects a collective discussion.

THIS SUMMER IN ICELAND, the country’s prime minister and a few dozen other government officials and scientists hiked to the site of Okjökull (Ok for short), a glacier that passed away four years ago. They held a memorial service on the naked rocks and affixed a plaque, with a message in Icelandic and English, to the ground. “Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier,” the plaque explains. “In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

As the plaque suggests, there is a lot we already know about the accelerated climate change that is coming. We know that it will occur even in the most optimistic scenario, which we are far from achieving. We know that it will entail devastating consequences everywhere, but especially in poor countries close to the equator, which will confront unprecedented droughts, floods, and heat waves; as a result, increasing waves of migrants will seek refuge in rich countries that are already experimenting with astoundingly cruel strategies to repel them. We know that a global transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy must happen now if we want to reduce the scale of the catastrophe, and that such a transition, if it is to be effective and just, must also include a shift toward socialism.

Like any time capsule, the Icelandic plaque expresses a hope that the future will at least produce understanding historians. And yet the gap between what we know and what we don’t about what lies before us is bewildering, not just scientifically or politically or emotionally, but also metaphysically. The kind of exhaustive doubt that plagues stoners and early modern philosophers—the kind that asks, with David Hume, why the sun rising today should be any indication that it will rise tomorrow—cannot be easily banished once glaciers begin to melt. Climate change is angry-god stuff, scrambling the coordinates of space and time that mortals use to anchor themselves to their world. “Plants and animals are increasingly out of sync with each other,” Astra Taylor reports in a recent essay in Lapham’s Quarterly: birds show up late for spring, flowers bloom and fade before bugs arrive to pollinate them. Climate change, producing sulfur emissions and insect swarms, is regularly described by way of the torments of the Hebrew Bible.

In short, climate change presents—among other things—a spiritual problem concerning what we often casually refer to as the end of the world. In another era, one might have expected to find the Jewish community embroiled in theological disputes about the nature and timing of the messiah. Indeed, as leftist Jews living in a period of planetary devastation, we’ve often thought of Walter Benjamin; the best-known Jewish sage to dwell on such questions in the modern era, he imagined history from the perspective of an angel caught in a storm called progress, flying with his back to the future as trash piles up endlessly in his line of sight.

But this association just as soon leads us elsewhere. In 1940, shortly after he wrote his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Benjamin died while attempting to escape Nazi-occupied Europe; Spanish border guards informed the group of refugees he was traveling with that they would not be permitted to enter Spain, and Benjamin overdosed on morphine rather than risk being sent back to Vichy France. He was obsessed with the ending of worlds—the world of 19th-century Paris, the world of his Berlin childhood—but it is impossible to read him now without thinking in particular of the Holocaust and the destruction of European Jewry; he is as bound to that catastrophe as Noah was to his flood.

This is often the way it goes, today, when we seek out Jewish ideas about end times: we immediately come upon an actual world that ended just a human lifespan ago. As the angel of history could tell you, Jews have this experience of total loss in common with a great many people and other creatures. Capitalist imperialism has been a particularly effective machine for the destruction of worlds, accompanied by the denial that they were ever there in the first place. Yet at the same time, the Holocaust is never merely an example; it has taken on a uniquely metonymic relationship to apocalyptic catastrophe as the result of both its actual singularity and reactionary attempts to isolate it from history altogether. As new endings approach, we’ve seen a spike in struggles over its memory.

ONE THING WE KNOW—because we are already seeing it—is that for many environmental migrants, the future will likely hold concentration camps. Yet when Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez accurately applied this language to ICE detention centers in June, American conservatives replied that the comparison was despicable, that the past must be kept safe from the present. The right’s treatment of Holocaust memory has become so cynical as to border on denial, oscillating between policing serious political discourse and trivializing the Shoah themselves. A few months after the excoriation of Ocasio-Cortez, the conservative columnist Bret Stephens implied in The New York Times that a (Jewish) Twitter user who jokingly compared him to a bedbug was engaging in the kind of hate speech directed at Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto.

In his book Remnants of Auschwitz, the philosopher Giorgio Agamben recalls being accused, in a letter to the editor of a French newspaper, of obscuring “the unique and unsayable character” of Hitler’s camps in an article he’d written. Agamben reflects that to create a taboo in which the horrors of Auschwitz, like the name of God, become “unsayable” serves to sacralize the Holocaust, “confer[ring] on extermination the prestige of the mystical.” And yet in a different sense, he continues, those horrors are unsayable. The Nazis sought to create what Carl Schmitt, national socialism’s most prominent jurist, called an Ausnahmezustand, a state of emergency or exception in which unchecked authoritarian power seizes control of the rule of law. This dystopian scenario was exemplified by the camps; in those microcosms of hell, Agamben writes elsewhere, “everything bec[ame] possible.” In the wake of the Shoah, the extremity of these conditions would become a hole in the middle of Holocaust testimony, isolating survivors in the incommunicability of their experience.

This duality—the simultaneous importance and impossibility of rendering the Holocaust “sayable”—is reflected in the current Holocaust discourse in American politics. The Jewish left, particularly young organizations like IfNotNow and Never Again Action, has forcefully rejected the grotesque misappropriations of Jewish history employed by the right. Though the insistence that we recognize the grim antecedents of contemporary US policy is necessary and admirable, it ultimately raises more questions than it settles. As Masha Gessen observed in The New Yorker, the fracas over the description of immigrant detention centers was only superficially about language. “Ocasio-Cortez and her opponents,” Gessen writes, “agree that the term ‘concentration camp’ refers to something so horrible as to be unimaginable.” The actual disagreement, then, concerned the question of whether the unimaginable could be imagined into present-day America—an “immeasurably more difficult” task “not so much because it is contentious and politically risky . . . but because it is cognitively strenuous. It makes one’s brain implode.”

AT THE STANDING ROCK ENCAMPMENT that attempted to halt the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, the historian Nick Estes recalls in Our History Is the Future, protesters developed a chant that could easily be mistaken for a more familiar one about democracy: “Tell me what the prophecy looks like! / This is what the prophecy looks like!” A Lakota prophecy from the late 19th century had foreseen the Zuzeca Sapa, an enormous black snake, stretching itself across Lakota land and bringing about the end of the world. When work on the pipeline began in 2016, it became clear to many in the area that the Zuzeca Sapa had arrived.

A recent strain of climate quietism has dismissed climate activism precisely on the grounds of its eschatological resonance. Climate activists, Jonathan Franzen wrote in September in The New Yorker, are like “religious leaders” who offer the masses “a false hope of salvation” in exchange for good works like biking to work or avoiding air travel. It’s not hard to see that the analogy relies on a caricature of political action peculiarly out of tune with the spirit of contemporary climate radicalism, which is all too aware that even the most dramatic successes will still be partial. But in order to ridicule activists as quack theologians, Franzen must caricature theology as well. “Other kinds of apocalypse, whether religious or thermonuclear or asteroidal, at least have the binary neatness of dying: one moment the world is there, the next moment it’s gone forever,” he writes. “Climate apocalypse, by contrast, will be messy.”

Climate apocalypse will be messy—but what religion imagines the end of the world unfolding neatly? In Benjamin’s Marxist recasting of Jewish messianism as the struggle for a classless society, the persistent salience of meditations on end times emerges from the fact that we’re in them already, and always have been. In the Jewish messianic tradition, as in the Lakota version, history continually threatens to burst into the present. In the course of such explosions, Benjamin’s follower Agamben explains in his book The Time That Remains, olam hazeh (this world) collides with olam habah (the world to come), creating a temporal rupture in which “the present is able to recognize the meaning of the past and the past therein finds its meaning and fulfillment.” In religious terms, this might look like the realization of a prophecy: a moment when ominous signs from the past become newly legible, revealing—as Benjamin puts it in his “Theses”—“a secret protocol between the generations of the past and that of our own.”

But Benjamin represents this claim in environmental terms as well. At the close of the same text, he quotes a “recent biologist” who observes that “[i]n relation to the history of organic life on earth, the miserable fifty millennia of homo sapiens represents something like the last two seconds of a twenty-four hour day.” The biologist’s view is like the angel’s: he pictures time on earth at a radically defamiliarized planetary scale, contracting the “entire history of humanity” into a “monstrous abbreviation.” From a contemporary perspective, we might say that we cease being climate change denialists only when we stop waiting for a sign that the world has begun to end and recognize that the million sites of crisis are the single overarching catastrophe.

Messianic time, here, describes not a particular epoch but the ongoing potential that we will come to see the world in a condition of perpetual crisis, as the angel (or, today, the biologist) does. For Benjamin, the task before us is to transform this de facto state of emergency—he uses the same term as Schmitt, Ausnahmezustand—into a real state of emergency: a revolution. From this perspective, the Ausnahmezustand that Hitler sought to establish was already latent in the experience of everyday life under capitalism. What were the camps, after all, but a vision of the status quo militarized beyond recognition, transformed into the Nazis’ own hideous utopia? And what would it look like to usher in a real state of emergency as the seas rise?

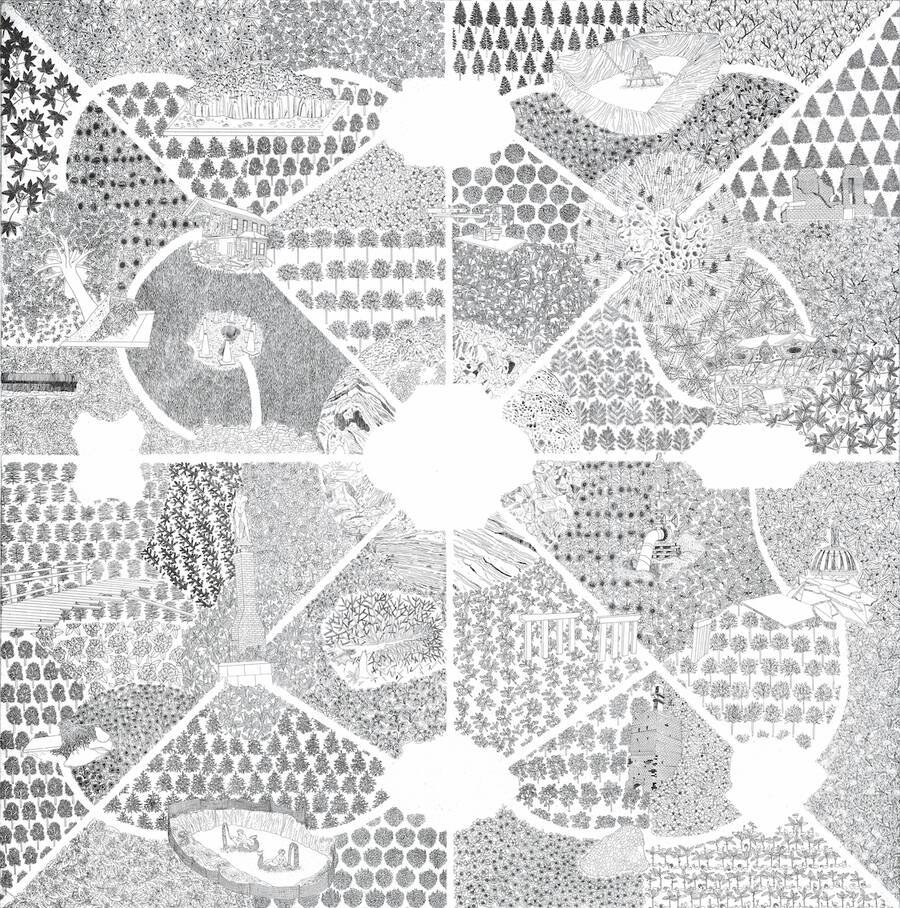

Today, Hitler’s camps stand between Jewish thought and the strange emergent timescale of climate change. When we conferred on extermination the prestige of the mystical, limiting our concept of the emergency to the one the Nazis created for us, we also became alienated from our own tradition of messianic thought—even as the ongoingness of Jewish life after the Holocaust offers the bleakest consolation that the destruction of a world is often incomplete, that life goes on after the disaster. As we head toward new confrontations, we are imagining a plan for a new kind of Holocaust memorial, one that remembers the camps as modernism’s most ambitious laboratory for a scorched earth. The memorial consists of a simple plaque recording the words of a midrash: If the messiah comes while you are holding a sapling, plant it.

Ari M. Brostoff is a writer in New York, and a contributing editor at Jewish Currents.