Happiness, As Such

An excerpt from a 1973 novel by Natalia Ginzburg, newly translated by Minna Zallman Proctor.

Natalia Ginzburg—author of more than a dozen books, including novels, story and essay collections, and plays—led a life marked by the brutality of 20th-century fascism. Born Natalia Levi in Sicily in 1916 to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, Ginzburg described her parents as fiercely secular “old-style Socialists.” In 1938, she married Leone Ginzburg, a former professor of Russian literature who had lost his position after refusing to swear allegiance to the National Fascist government of Italy, and who had been intermittently imprisoned for antifascist activity. The couple secretly edited an antifascist newspaper, L’Italia Libera. When the Nazis invaded, they went into hiding along with their three children. Ginzburg’s husband was eventually captured, tortured, and executed for his political activities. Ginzburg survived the war and remained politically active as a member of the Italian Communist Party, and later, in 1983, as an elected official in the Italian Parliament.

Ginzburg’s work, beloved in Italy, is currently undergoing a revival in the Anglophone world. The renaissance began when Arcade Publishing released a new edition of her essay collection The Little Virtues in 2016. The next year, NYRB Classics issued a new translation of her autobiographical novel Lessico famigliare—widely considered to be a masterpiece—under the title Family Lexicon. This summer, New Directions is publishing new translations of two short novels: Frances Fenaye’s translation of The Dry Heart and Minna Zallman Proctor’s translation of Happiness, as Such, from which the following chapter is excerpted.

With the exception of her first novel—which appeared under a pseudonym because of fascist laws that barred Jews from publishing—all of Ginzburg’s work was published after the war’s end, and it bears its indelible imprint. During the 1940s, Ginzburg worked at Einaudi, the publishing house her husband co-founded, which released works by Primo Levi and Italo Calvino, among many others. There she saw firsthand the effect that the devastation of World War II was having on the written word. In Family Lexicon, the narrator outlines two flawed directions for postwar writing: one a “simple listing of facts outlining a dreary, foul, base reality” and the other a “mixing of facts with . . . a delirium of tears, sobs, and sighs.” She then suggests a way out of this dichotomy, a means of recentering as a writer. “It was necessary,” she says, “for writers to go back and choose their words, scrutinize them to see if they were false or real, if they had actual origins in our experience, or if instead they only had the ephemeral origins of a shared illusion. It was necessary, if one was a writer, to go back and find your true calling that had been forgotten in the general intoxication.”

That search for reality led Ginzburg to her particular poetics. Though the forces of history and politics are palpably present in Ginzburg’s stories—intruding on characters’ lives in major (and often lethal) ways—these intrusions often occur off the page, in the narrative margins. Instead, the focus is on quieter moments between characters: small idiosyncrasies of speech and habit; the things they feel deeply but leave unsaid. History and politics, Ginzburg’s work reminds us, are a matter of a grand accumulation of common, capacious individual lives—lives that she manages to evoke in their complexity in a minimalist style, coursing with electricity. In a few strokes, she renders worlds. In this way, Ginzburg’s particular kind of political fiction can serve as both inspiration and refuge as we again live through a time in which nothing is certain, and everything is at risk.

DECEMBER 3, 1970—LONDON

Dear Angelica,

I left in such a hurry because they called in the middle of the night to tell me Anselmo had been arrested. I called you from the airport but you didn’t answer.

I’m sending this letter with someone—he’ll bring it to you by hand. His name is Ray. I met him here. He’s from Ostend. He can be trusted. Give him somewhere to sleep if you have room. He needs to stay in Rome for a few days.

I need you to go to my house right away. Make up some excuse to get the keys from Osvaldo. Tell him you need a book. Tell him whatever you want. Don’t forget to bring a suitcase or bag with you. There’s a dismantled machine gun wrapped in a towel, inside the wood stove. I totally forgot about it before I left. That will seem strange to you but it’s how it was. My friend Oliviero brought it to me one night a few weekends ago because he thought the police might search his place. I told him to tuck it in the stove. I never light that stove. It burns wood and I never have wood. I hid the gun in the stove and then forgot all about it. I remembered after I was on the plane, already in the air. It was like I suddenly got drenched in a boiling sweat. They say fear makes you break out in a cold sweat. That’s not true. Sweat can be boiling. I had to take off my sweater. You should bring a suitcase or bag to put the gun into. Unload it onto someone you’d never suspect. Like the woman who comes to clean for you. Or you could get it back to Oliviero. His name is Oliviero Marzullo. I don’t have his address but someone does. Now that I think about it, the gun is so old and rusty you could just throw it in the Tiber. I’m not asking Osvaldo to do this for me, I’m asking you. I’d actually prefer if Osvaldo never knew. I don’t want him to think I’m a complete imbecile. But if you feel strongly that you want to tell Osvaldo, go ahead. If he ends up thinking I’m an idiot, what do I care.

Of course my passport had expired. Of course Osvaldo helped me get it renewed, all in a matter of hours. Gianni was at the airport too and we got into it because Gianni thinks there’s a fascist spy in the group. Maybe more than one. I’m sure he’s just imagining things. Gianni won’t leave Rome but he never spends more than one night in the same place.

I stopped by to see our father before I left. Osvaldo waited for me in the car. Father was fast asleep. He looked very old and very sick.

I’m well. My room here is long and narrow and the wallpaper is tattered. Everything about this place is long and narrow. There’s a hallway and all the bedrooms open off the hallway. There are five of us boarding here. We pay four pounds a week. The landlady is a Romanian Jew who sells skin cream.

When you have time, will you go see a girl I know who is staying on Via dei Prefetti. I don’t remember the address but Osvaldo has it. Her name is Mara Castorelli. She just had a baby. I gave her money for an abortion but she didn’t get it. I slept with her a few times so the baby could be mine. She was with a lot of men though. Bring her a little money if you can.

Michele

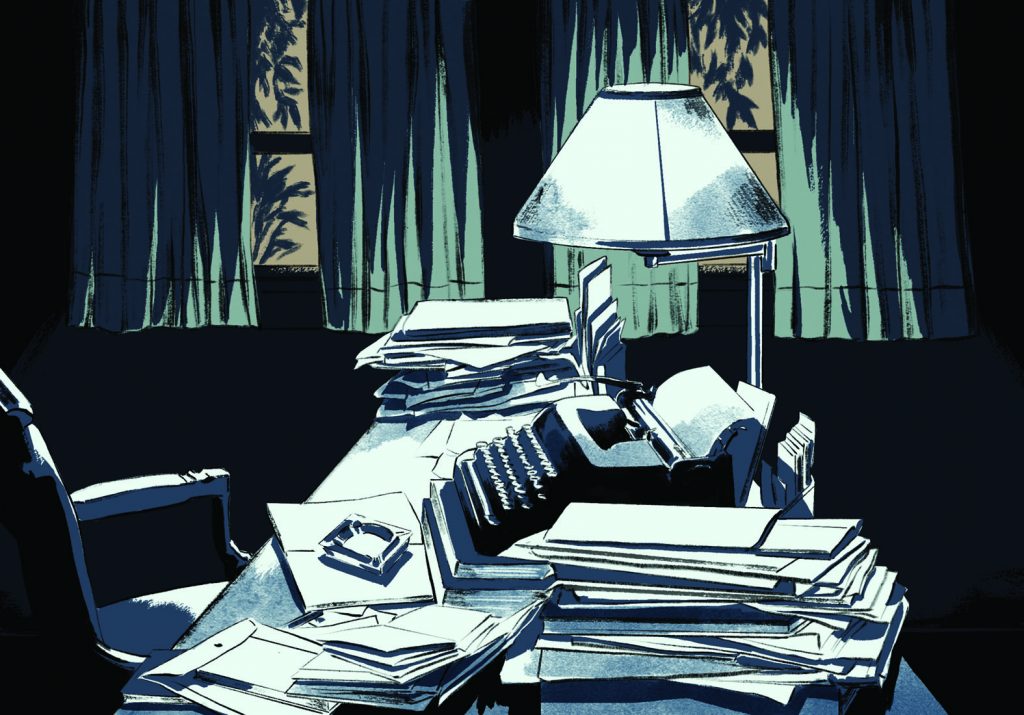

ANGELICA WAS SPRAWLED on the couch in her dining room reading the letter. It was a small, very dark, dining room. The table took up almost all the space and was overflowing with books and papers. A lamp and a typewriter teetered on top of the stacks. Oreste, her husband, worked at the table, but he was in the bedroom now sleeping because he worked nights at the newspaper and usually slept until four in the afternoon. The kitchen door was open and she could see her friend Sonia with her daughter Flora, sitting with the boy who’d brought the letter. Flora was eating bread dunked in Ovaltine. She looked like a green, five-year-old girl lizard—wearing a blue pinafore and red wool tights. Angelica’s friend Sonia was hunched over the sink washing last night’s dishes. She was tall, shy, and wore glasses. Her long, black hair was pulled back into a ponytail. The boy who’d brought the letter was eating a plate of reheated penne with tomato sauce leftover from Oreste’s dinner. He wore a faded turquoise windbreaker that he didn’t want to take off because he’d caught a chill while traveling. His short, chestnut beard was sparse and well groomed.

Angelica finished reading the letter and stood up from the couch to look for her shoes under the carpet. Her tights were the color of moss. She was wearing a rumpled sweater that she’d been wearing since the day before at the hospital. Her father had gone into surgery and died overnight.

Angelica twisted her fine blond hair into a bun on top of her head and secured it in place with several combs. She was twenty-three years old. She was pale, tall, and her face was a little too long. Her eyes were green like her mother’s but shaped differently—long, narrow, and slanted. She pulled a flowered black tote down from the wardrobe. She already had Michele’s studio keys from Osvaldo because she had planned to collect his dirty laundry and take it to the cleaners. The keys were in her jacket pocket. It was a black nylon jacket she’d bought used at Porta Portese. She put it on, called into the kitchen that she was going out shopping, and left.

Her Fiat was parked in front of Chiesa Nuova. She climbed into the car and sat for a moment without moving. Then she drove toward Piazza Farnese. She remembered a day last October when she’d run into her father on Via dei Giubbonari. He was walking toward her with his long stride, hands in his pockets, long, black curls swept back in the wind, his tie blowing, that black alpaca coat, as always, rumpled and unbuttoned, his broad brown face and large mouth, the expression bitter and disgusted, as always. She had been coming out of the movies with her daughter. He extended his hand, soft, sweaty, limp. They hadn’t kissed each other in years. They didn’t have much to say either since they didn’t see each other often. They got some coffee and stood at the bar. He bought the child a big, cream pastry. When Angelica expressed doubt that it was fresh, he was offended and said that he always came to this bar and he’d never had an old pastry. He told her that a friend of his lived right upstairs, an Irish cello player. While they were drinking their coffee, the Irish woman showed up. She was plump and not beautiful, her nose looked like a shoe. They were going out to look for coats because the Irish woman wanted to buy one. They all went together to a clothing store in Piazza del Paradiso. The Irish woman tried on coats. Her father bought a poncho with pictures of deer on it for Flora. The Irish woman picked out a long, black, buckskin coat lined with white fur that she was very pleased with. Her father paid, pulling a handful of crumpled bills from his pocket. The edge of a handkerchief stuck out of his pocket. He always had a bit of handkerchief coming out of his pocket. Then they went to the Medusa Gallery where her father was hanging a show that was about to open. The gallery owners were two young men in leather jackets who were determined to handwrite the invitations to the opening. The paintings were almost all hung and there was a big portrait of her mother, painted many years earlier when her mother and father were still together. Her mother was at the window, hands folded under her chin. She was wearing a blue and white striped shirt, her hair a cloud of fiery red. Her face was a parched triangle, sardonic and full of lines, while her eyes were heavy, contemptuous, and dim. Angelica remembered their house on Pieve di Cadore where they lived when he’d painted that picture. She recognized the window and the green awning over the terrace. The house had been sold later. Her father paused in front of the painting, his hands in his pockets, and he spent a long time praising the palette which he described as acid and cruel. Then he commenced praising every one of his paintings. Recently he’d started working on an enormous scale, using canvases upon which he’d piled every manner of object. He’d discovered a heaping technique. Boats, cars, bicycles, trucks, dolls, soldiers, gravestones, naked women, and dead animals, floating in a murky green haze. In his bitter, gravelly voice, her father said that no one working in that moment was able to paint with such vastness and precision. His work was tragic and solemn, gigantic and detailed. He referred to “my pain-ting,” landing on the t with an asthmatic flourish—solitary and painful. Angelica didn’t believe a word of what he was saying and thought that the Irish woman and the gallery owners didn’t either—maybe her father didn’t believe a word he was saying or the grating way he was saying it. His voice echoed piercing and isolated. A broken record. Angelica suddenly remembered a song her father used to sing while he was painting, a childhood memory. It had been many years since she’d been there when he was painting.

Non avemo ni canones

Ni tanks ni aviones

Ay Carmelà!

She asked him if he still sang “Ay Carmelà!” when he painted and he seemed surprisingly moved. He said that no, he didn’t sing anymore, the new paintings took too much effort. He painted while balancing on a ladder, and he sweated so much he had to change his shirt every two hours. He seemed suddenly anxious to be liberated from the Irish woman. He told her that it was getting dark and that she should go home. He wasn’t able to walk her because he had a dinner engagement. The Irish woman hailed a taxi. He spoke sharply to her about always taking too many taxis even though she came from the remote Irish countryside where there were no taxis, just fog, peat, and sheep. He took Angelica under the arm and walked her and the child home to Via dei Banchi Vecchi. On the way there, he started complaining. He was alone. His butler was a fool who used to work in a car repair shop. No one ever visited him. He practically never saw the twins who’d gotten fat recently, they were only fourteen years old and weighed fifty-eight kilos each. One hundred and sixteen kilos all together, he said, it was too much. He almost never saw Viola, who, to make matters worse, he could barely stand because she had no sense of irony. She and her husband were shacked up in his parents’ house. So many people under one roof—in-laws, uncles, aunts, grandchildren. It was a commune. All those relatively insignificant people. Pharmacists! Not that he had a problem with pharmacies, he’d said, ducking into a drugstore to buy some Alka-Seltzer for the great pain he had “right here” he said, pointing to the middle of his chest, a dull pain, maybe that old ulcer—his aged and faithful life companion. He’d barely seen Michele recently, which troubled him. He’d agreed it was the right thing when Michele moved out to live on his own, but it was sad. When he spoke of Michele his voice softened, as if beaten—it didn’t have that grating quality. But Michele was always with that Osvaldo man now. He couldn’t quite understand what kind of person Osvaldo was. Obviously he was very nice. Polite. Unobtrusive. Michele dragged him around everywhere, even to Via San Sabastianello when he came over to do his laundry. Likely he needed Osvaldo to give him a lift in the car. Michele didn’t have a car anymore. He’d lost his license after hitting that old nun. She died but it wasn’t Michele’s fault. Not entirely Michele’s fault. He had only just learned how to drive and was speeding because he was going to his mother’s who needed him because she was depressed. She was always depressed. Their mother, he said, lowering his voice to a husky whisper, couldn’t stand to be alone and in her infinite stupidity hadn’t known that Cavalieri had been planning for some time to leave her. She was naive. At forty-four years old, she had the mentality of a teenage girl. Forty-two, said Angelica, she’s turning forty-three soon. Her father made a brisk calculation on his fingers. She is more naive than the twins, he said. And worse, the twins aren’t disingenuous. They’re cool and calculating—like two wolves. Either way Cavaliere had never impressed him much. He never, never ever seemed nice. His sloped shoulders and long white fingers, his hair in ringlets. From the side he looked like a hawk. Her father said he could always recognize a hawk. When they reached Angelica’s front door, he said he didn’t feel like coming up because he didn’t care much for her husband Oreste—he’s pedantic. Sanctimonious. Her father didn’t kiss Angelica or the little girl, but he chucked the girl under her chin and squeezed Angelica’s arm. He encouraged her to come to the opening the next day. The show was going to be a “big deal.” He left. Angelica missed the opening because she went to a conference in Naples with her husband. After that day, she only saw her father again two or three times. He was sick in bed and her mother was there. He didn’t say anything to her. One time he was on the phone. Another time he was feeling unwell and just gestured in her direction, distracted and disgusted.

Angelica climbed six flights up to the studio. She turned on the light as she entered. There was a bed in the middle of the room, the sheets and blankets in disarray. Angelica recognized her mother’s beautiful blankets. Mother loved buying nice blankets, warm and lightweight, soft with velvet trim, lovely pale colors. The floor was cluttered with empty bottles, newspapers, and paintings. She glanced at the paintings—vultures, owls, abandoned houses. The dirty laundry was by the window, along with a pair of wadded up jeans, a tea kettle, an ashtray full of cigarette butts, and a plate of oranges. The wood stove was in the center of the room. It was large and round, with a green enamel door in a delicate ornamental design that looked like lace. Angelica reached an arm into the stove and fished out a bundle wrapped in an old frayed towel. She tossed it into the tote bag. She also took the laundry and the oranges. She left the workshop and walked for a while in the damp, foggy morning, turning up her jacket collar to shield her mouth. She dropped off the dirty clothes at a nearby laundry, called Fast Wash. She had to wait at the counter while they counted the clothes one by one. Then she got back in her car. She drove slowly through traffic to the Lungotevere Ripa. She climbed down the stairs leading to the river bank. She threw the bundle into the river. A child asked her what she’d thrown into the river. She told him they were rotten oranges.

“Non avemo ni canones . . . ni tanks ni aviones,” she sang as she made her way home through the traffic. All at once she realized her face was wet with tears. She laughed, sobbed, and wiped her tears away with her jacket sleeve. When she got close to her house, she bought some pork loin to poach with potatoes. She also bought two bottles of beer and a box of sugar. Then she bought a black scarf and a pair of black stockings to wear to her father’s funeral.

Natalia Ginzburg (1916–1991) was a writer of novels, short stories, essays, and plays. An antifascist activist, she was involved with the Italian Communist Party and was elected to the Italian Parliament in 1983. Her books available in English include Family Lexicon and The Little Virtues.

Minna Zallman Proctor is the author of Landslide and the editor of The Literary Review. She won the PEN/Renato Poggioli Award for her translation of Frederigo Tozzi’s Love in Vain.