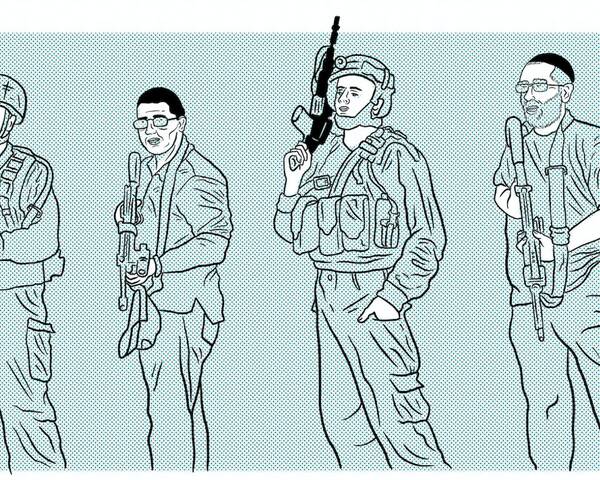

Letters / On “When Settler Becomes Native”

As someone who is both Jewish and Native (Quechua), I greatly appreciated “When Settler Becomes Native” in your Fall issue. It’s a concise but thorough resource that I will definitely be recommending. Unfortunately, the piece also engages in Indigenous erasure and anti-Native language.

Firstly, the piece suffers from an overall failure to mention Native/Indigenous Jews. Jewish Natives are already invisibilized in the Jewish community, yet our voices and experiences are of critical relevance to this conversation. Our omission here is not only notable, but also counterproductive. The single Native Jew mentioned is a Zionist, even though Jewish Natives (like non-Jewish Natives) lean anti-Zionist.

When the piece does cite specific Native people, it uses language that implicitly questions their legitimacy. It refers to Métis and Tewa individuals as being “of [Native] descent” and puts “Indigenous advocate” in scare quotes. By contrast, the Mizrahi Jews quoted are not referred to as “of Mizrahi descent.”

The language of “descent” plays into the idea that true Nativeness is defined by so-called pure blood, rather than by belonging to a living Native community—a dynamic the author references in the comic, but still replicates. It reinforces the anti-Indigenous trope that due to racial mixing and cultural adaptation, there are no “real” Natives left. It would have been better, in this case, to refer to these individuals simply as being “Métis” and “Tewa,” clearly stating the nations they belong to.

Chuk’shon, O’odham Jewed (Tucson, AZ)

I found JB Brager’s recent comic interesting and engaging, but I’m frustrated by the discussion of this issue as a simplistic binary: either Jews are Indigenous to Palestine and are therefore entitled to a Jewish state while Palestinians have no such right, or Jewish claims of indigeneity to Palestine are entirely invalid. Why can’t Israeli Jews and Palestinians both legitimately claim Indigenous status in Israel/Palestine? As long as both are prepared to live side-by-side as equals, there is no necessary conflict. Our tradition teaches that land belongs to G-d alone: It’s not about which people the land belongs to, it’s about which people belong to the land, and that belonging does not have to be exclusive.

One could say that 2,000 years of exile have extinguished Jewish claims to indigeneity in Palestine. But that line of reasoning accepts the legitimacy of conquest as a basis for determining who belongs where. It is imperialist thinking: Might makes right. By that same reasoning, if Israel succeeded in ethnically cleansing Palestinians from the land, and managed to keep them out for an unspecified number of generations, the exiled Palestinian people would likewise cease to be Indigenous, and their hopes for return would become invalid.

On the contrary, it is the persistence of Jewish attachment to Eretz Yisrael over two millenia of galut [exile] that makes it all the more galling that many Jews can’t recognize the same attachment among Palestinians, as Peter Beinart has pointed out in his essay “Teshuvah: A Jewish case for Palestinian Refugee Return.” Rather than being a zero-sum contest about which people is the real Indigenous one, perhaps a shared, mutually recognized sense of indigeneity could lead Israeli Jews and Palestinians to sharing the land as equals.

Amiskwaciwâskahikan (Edmonton, Canada)

The recent comic “When Settler Becomes Native” speaks to important issues around Jewish claims to indigeneity in Israel. However, a Mizrahi friend brought to my attention that it would have been more appropriate to depict Ashkenazi activists making these claims. Pointing to comments made by Hen Mazzig and Rudy Rochman, two Mizrahi Jews, can be experienced as racist, leaving much out of the conversation around identity. Though anyone can perpetuate racism regardless of their race, in this case it seems inappropriate to have those representing these claims be Mizrahi Jews, who have a much more complicated history with the land of Palestine than Ashkenazi Jews.

Squaxin, Nisqually, Chehalis land (Olympia, WA)

I appreciate the tremendous work that went into pulling together many complex strands in the comic “When Settler Becomes Native.” In my organizing with Jews on Ohlone Land and in my studies of Jewish relationships with Indigenous people, I’ve circled around similar topics. What I feel is often missing from these conversations, and is absent from JB Brager’s comic, is the possibility that Jewish people are both ancestrally Indigenous to the land of Palestine and acting predominantly as settler-colonists in their current relationship with the land and people.

The comic locates indigeneity in a relationship to a colonial history and present. This is an important frame, but it is one of many ways to locate indigeneity, some of which contradict each other. Allowing for inconsistencies can be part of disrupting colonization, as the scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang have written. Indigeneity can be read as both a binaried construct (i.e. Indigenous vs. colonist) that serves colonization and as a set of ontologies that exist beyond the colonial gaze. Indigeneity can be defined both in service of colonization and in support of Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty.

Who, then, can claim indigeneity, and to what ends? Is it impossible for those currently acting as oppressors to ever have been Indigenous? Or to ever “unbecome” colonists, as the French Tunisian writer Albert Memmi has asked? It seems to me not only that Jewish people everywhere in the world can be ancestrally Indigenous to the Levant, but that we can learn from our heritage as one method of disidentifying with and disrupting systems of colonialism. These processes also have important things to teach Jews living in diaspora, most of whom are living on colonized Indigenous land.

Huichin (Berkeley, CA)