Fables of Finitude

In Pure Colour, Sheila Heti asks what it would mean to love the stories that link us to the past without imagining that they will carry us into the future.

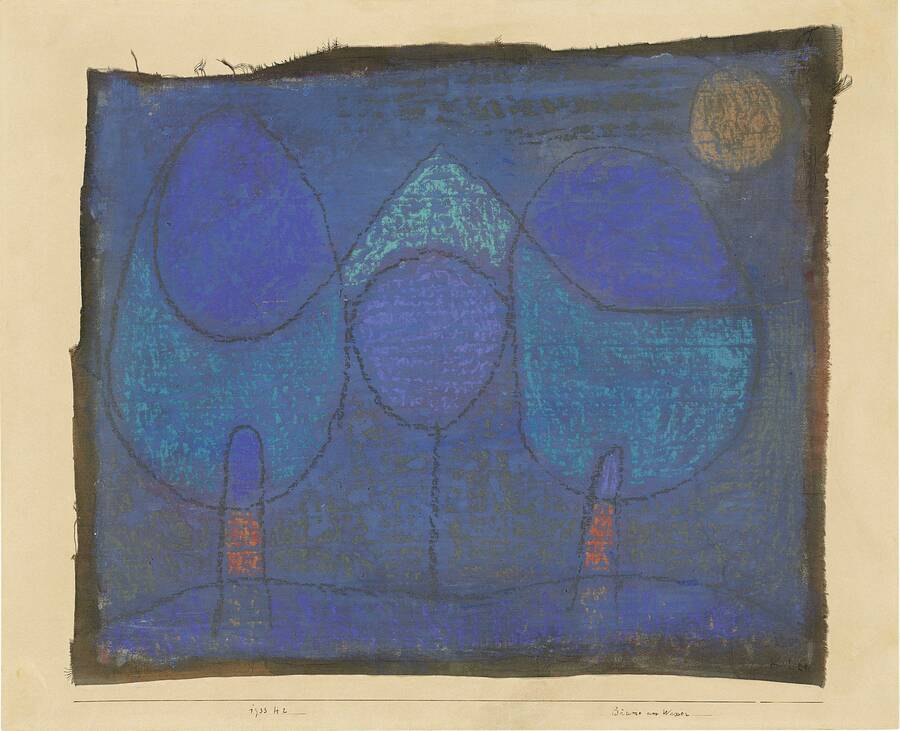

Paul Klee: Trees by the Water

Discussed in this essay: Pure Colour, by Sheila Heti. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022. 224 pages.

Throughout Sheila Heti’s 2018 novel Motherhood, the narrator struggles to decide whether she wants a child—and, by extension, whether she cares about staking a claim to the future, which descendants are supposed to ensure. At times, she seems to hope that by refusing parenthood, she can reject the axiom that the measure of a life is its legacy: Why, she wonders, should she feel obligated to keep her family line from ending when she “[doesn’t] really care if the human race dies out”? But in other moments, she expresses a wish to secure, through her writing, a foothold on eternity. “I want to make a child that will not die,” she says, “a body that will speak and keep on speaking.” In an interview with The Paris Review, Heti argued that her childless narrator is still engaged in a kind of reproduction, as she is herself. “Like a mother, I’m trying to imprint myself on the world in some way,” she said. “I’m not in the superradical place of not needing to leave anything behind. Being legacyless seems really radical to me. It seems almost saintly.”

In her new novel, Pure Colour, Heti writes her way further into that sanctified void. The protagonist, a young woman named Mira, begins as an adherent of the same school of futurism as Motherhood’s narrator. An aspiring literary critic, she believes the purpose of her life is “ushering books forth . . . past [their] awkward and irrelevant years, down through the civilizations.” But the death of her beloved father sets her life spinning on a different course. Trapped in the endless present of deep mourning, Mira can no longer relate to the former self who faced relentlessly forward; as she assimilates the fact of mortality, she becomes sanguine about the idea that even art has a limited lifespan. “It’s clear to me now that art is made for our situation,” she thinks. “Whatever comes will be another situation, and our art won’t be needed for it . . . it’s not sad for things to be useful in their time.” Eventually, Mira abandons her vocation as a critic for a life of finite pleasures and a dead-end job behind the counter at a jewelry store.

Perhaps it’s for the best that Mira’s hunger to leave a legacy dwindles, because in the world of Pure Colour, there will be no future generations to value her work. On the first page of the novel, God himself appears in the guise of a frustrated artist-critic, assessing creation “like a painter standing back from the canvas,” and concluding that “the first draft of existence” should be scrapped. Whatever might come in the second draft, it seems that the old world will leave barely a trace on the new, at most coloring the dreams of its inhabitants with a faint intuition of loss. But before starting over, God decides to study the flaws of the first draft by enlisting all of humanity as critics, not to canonize the best parts of creation but to locate every error that must be undone. To ensure thoroughness, he divides us into three animal types—artistic birds who look at the world “from on high,” principled fish who prioritize “the conditions of the many,” and clannishly loving bears, “deeply consumed with their own”—who will scrutinize creation from three distinct angles. Plied to separate purposes, the three kinds of people can’t understand each other, which leaves the bird-like Mira painfully divided from her bearish father and from the woman she falls in love with, a fish named Annie. As the novel progresses, its quiet interpersonal drama intersects with its antic cosmology: After her father’s death, Mira rejects her place in God’s instrumentalist schema to hide out with her father’s soul inside a leaf. Musings about the meaning of life ensue. Mira escapes the leaf, then wishes she could return to it. Annie warms up and then freezes over. Mira’s betrayal deepens; God looks away.

Trapped in the endless present of deep mourning, Mira can no longer relate to the former self who faced relentlessly forward; as she assimilates the fact of mortality, she becomes sanguine about the idea that even art has a limited lifespan.

This mercurial fabulism marks a departure for Heti, whose previous experiments have blurred the line between fiction and nonfiction but left metaphysical boundaries intact. The impulse to invent a new folklore seems inextricable from the endings that hang over the novel’s unfolding action—which include not only human mortality but also the loss of pre-digital society and, most pressingly, climate catastrophe. (Sitting by a lake, Mira reflects, “One day the lake would flood the whole city from the ice caps melting into the sea, and the whole city would be destroyed, and anyone she had ever called a friend, and that log, and this leaf, and everyone.”) In his 1936 essay “The Storyteller,” the philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin describes fairy tales as narrative forms that historically addressed a “need created by the myth,” specifically the need “to shake off the nightmare which the myth had placed upon [mankind’s] chest.” Pure Colour contains both the nightmare and the answer to it: If the novel’s artistically frustrated God is the myth that helps structure a looming sense of apocalypse, its more open-ended animism—its tales of birds trying to become bears and people preferring to live as leaves—elaborates how people might carry on under the myth’s weight.

For Benjamin, fairy tales and fables are not only sources of “counsel,” but also instruments of cultural transmission. In the pared-down form of the proverb, they become, he writes, merely “a ruin which stands on the site of an old story and in which a moral twines about a happening like ivy around a wall.” The intent of a fable is not only to tell its listeners how to live, but to twist its tendrils into the imaginations of future generations, planting the seeds of norms and traditions. In Pure Colour, this intimate inheritance is a source of beauty; long after her father’s death, Mira’s greatest satisfaction comes from performing small tasks in exactly the way he taught her to. The novel is the fullest expression to date of a tension that animates much of Heti’s work, between an attachment to the practice of handing things down and a desire to turn away from a future that it sometimes seems we have already forfeited. Heti asks if we can honor the knowledge that has been given to us, and the forms that were created to carry it—including, perhaps, that of the novel itself—while decoupling both the counsel and its container from their original purpose of self-perpetuation. What would it look like to love the stories that link us to the past without imagining that they will carry us into the future? With its strange fables of finitude, Pure Colour remakes narrative vehicles of cultural continuity into pearls of wisdom for the end of the world.

With its strange fables of finitude, Pure Colour remakes narrative vehicles of cultural continuity into pearls of wisdom for the end of the world.

Heti’s fiction has always been anti-teleological, though her earlier books are less cosmic in scope, concerned with individuals’ circular efforts to travel through life in something like a straight line. In her 2012 novel How Should a Person Be?, the narrator, a recently divorced writer in her late 20s, reckons with regression in both her personal life and her career. Motherhood is recursive in its very structure, following the looping pattern of the narrator’s menstrual cycle and the spiraling roller coaster of her moods. Though understood at the time as part of the boom in autofiction, both books were in reality something more unusual; where most works in the genre propel themselves through constructed epiphanies, Heti undermines the authority of her narrators’ testimony, emphasizing their incoherence and malleability. Her avatars seek advice endlessly, from friends, acquaintances, street bench psychics; the text of How Should a Person Be? includes transcriptions of Heti’s real-life attempts to canvass her artistic collaborators for insight, while the narrator of Motherhood seeks to divine her desires with an I Ching-like exercise that Heti herself undertook.

Heti’s prose is unforced, even diaristic, deriving philosophical depth from apparent naivety. The characters ask profound questions in child-like terms that defamiliarize the adult world’s punishing prescriptions. (For example, in Motherhood: “Since life rarely accords with our expectations, why bother expecting anything at all?”) By refusing the answers already on offer, Heti’s work attains a startling, sui generis glow, like a crystal grown deep underground that looks starkly alien when brought to the earth’s surface. Sometimes this quality seems to require a level of intellectual seclusion: Motherhood blithely bypassed the long tradition of thought about how one might be both a mother and an artist, or a feminist mother whose child is not her sole concern. After its publication, Heti explained that she originally intended to review academic treatments of the subject, but decided to consume only mainstream popular writing, so that “the mind that wrote the book [would] be the nonartist version of myself.” This lack of intellectual rootedness sometimes makes her philosophizing feel gestural. Inside the leaf in Pure Colour, Mira and her father discuss human nature in an idiom that reads as if borrowed from yoga class, lamenting the part of us that “wants to win” and praising the “loving part” that “shines through us so beautifully.”

Even as they leave contemporary source material on the table, Heti’s protagonists do often turn to inherited texts, especially Jewish ones. The narrator of How Should a Person Be? takes comfort in the model of Moses, whose many imperfections give her hope that, despite her shortcomings, she might say something meaningful with her art. In Motherhood, the speaker sees the story of Jacob wrestling with the angel as a template for her own struggle, in which she begins to suspect that she too is seeking a blessing from the thing she confronts. But if Heti finds her own religious tradition to be rich territory, she seems constitutionally rankled by what the queer theorist Lee Edelman, in his provocative 2004 book No Future, calls “the secular theology on which our social reality rests”: the reproductive futurism in which the figure of the child—the idea of a successor—justifies our present political order and the choices that structure our individual lives. The doctrine exerts its hegemony over fiction, as well. In recent novels like Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You? and Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This, the act of having (or even simply loving) a child stands in for the achievement of hard-won optimism, signaling that the characters have confronted the same apocalyptic anxieties that cloud Pure Colour and cast their lot with the rest of humanity all the same. Heti explicitly refuses this trope: In Motherhood, the narrator announces her intention to write for her ancestors instead of toward imagined descendants. “Art is eternity backwards,” she says. “Children are eternity forwards.”

While the narrator of Motherhood turns her mind toward her forebears, Mira devotes her very body to the problem of keeping the past alive. Upon her father’s death—in one of the novel’s most discomfiting passages—she feels his spirit “ejaculate into her.” Heti makes sure the reader does not overlook the sexual nature of the experience, writing that it feels “the way cum feels spreading inside.” Mira gestates a departed soul, even cutting back her smoking and drinking for the good of the pregnancy. “It was the dead . . . who needed us most,” she thinks. “Who would save the dead from oblivion, if not we, the living?” Fabulism irrupts in response to the extremity of Mira’s grief, the laws of the universe bending to make room for her longing to resist the forward march of generational time.

This turn toward the surreal not only upends the natural order, but subverts the conventions of folklore, as well. Fairy tales often begin with the death of a parent, but the loss always propels the hero into the world. Consider Cinderella, whose mother’s death makes her a servant in her father’s house, inciting a series of actions that end with her happy ensconcement in a prince’s castle, where she has found a new fate and family. Mira’s story traverses the same terrain backward: In life, her father expressed his love by pushing her to go forth in pursuit of greatness; after his death, she retreats to the close quarters of their shared leaf. The content of fairy tales counsels us to keep going, and the form passes that message between generations; Heti’s revision, in its search for stillness, challenges both prescriptions at once. If the world is ending, it leaves us in need not of stories about how to persevere, but of tales about how to accept not persisting. Enter Mira, who demonstrates how to endure loss by showing how one might simply not move on.

In Heti’s theology, Mira’s abnegation may be somehow saintly, but it is also a heresy that offends God. Sitting inside the leaf after attempting to accompany her father into nonexistence, Mira realizes she has transgressed: “What had she done in coming into a leaf? And would the universe, which had its own laws, ever forgive her for distorting them?” Even after returning to human form, Mira remains mutinous toward a god who treats human beings like “expendable soldiers” in his ongoing investigation of creation, making “sensitive creatures . . . simply to serve [his] own ends.” She no longer wants to be a bird—which is to say, a human aesthete—tasked with tallying the world’s lack of order and harmony. She comes to see the critical impulse that she once nurtured as a hook fashioned from the heart of her being by a deity who uses her to go fishing for insight. Mira decides to disobey God by abdicating her role as a critic, remaining leaf-like even in human life:

She would not give her opinion about anything. She would take no actions, and would remain in one place, like a leaf does, and when she died, she would fall to the ground. A leaf remains on the branch on which it’s been grown, it does not change the world around it. She would not go into the world to critique or fix it . . . She would look at the world only to love it—and God, her creator, would hate her.

Heti seems neither to endorse nor to condemn Mira’s betrayal, but to see it as an inescapable condition of life. “The child is never who the parent wants them to be, and they must not be,” she writes, in a line that could describe Mira’s relationship to either one of her creators. “A child must follow the rules of her own being.” Mira’s nature shows itself early in the novel, when, as an aspiring critic, she works in a store that sells Tiffany lamps, and finds herself drawn to the “essential humility” of the simplest one, in which red and green orbs glow unadorned. In school, she silently disagrees with a professor who criticizes the art of Édouard Manet for “ridiculing our spiritual pretensions” with its prosaic formal vocabulary. Mira loves Manet’s painting of a single asparagus, “the simplicity of his expression, the lightness of his touch, the muteness of his colours, how minor a thing an asparagus is . . . the delicate and unassuming heart he put into every line.” (So does Heti, who also includes a rapturous description of Manet’s work in How Should a Person Be?.) Both God and Mira’s father wish, for reasons of their own, to see her reach great heights as a critic. But Mira’s real talent seems to be for noticing beauty at its most modest, appreciating the humblest objects as art.

It’s tempting to look for heroism in Mira’s refusal to turn her critical impulse—which she summarizes as “the desire to undo things”—toward the apocalyptic purpose that God intends. But the novel doesn’t suggest that we should resist the end of the world, or even that it’s such a bad thing; the second draft, after all, “will be better . . . in all the ways that count.” Mira’s wisdom seems to consist not in shirking a role in her own destruction, but in realizing that, in the face of the cessation of everything, it makes no sense to treat our time on earth as a means to an end. Just as Heti rescues fables for finitude, divorcing them from the purpose of continuity, Mira prunes back her life, cutting away branches sustained for the fruit they might someday produce, withdrawing into the intrinsic pleasures of an unbreachable introversion that is justifiable entirely on its own terms.

If the world is ending, it leaves us in need not of stories about how to persevere, but of tales about how to accept not persisting.

Even as Mira settles into a refusal of futurism, she never renounces her desire to “save the dead from oblivion”—but how can one preserve the past without acceding to the importance of perpetuity? Heti’s temporal experiments point toward a possible answer. In Pure Colour, the structuring logic of time shifts without warning beneath the text’s surface. Decades slip by unexplained, or chronology sputters and stalls: The novel narrates the moment of Mira’s father’s death in four distinct passages, retracing the instant of transformation like Genesis with its competing versions of creation. By loosening the hold of linear time, Heti slips free of the assumptions and values inherent in narrative. These formal choices insist, as the narrator asserts, that “if progress in human history is an illusion, so is progress in a human life.” Heti explores similar themes in a serialized project published this winter in The New York Times, composed of sentences from a decade’s worth of her diaries rearranged in alphabetical order. By divorcing the material from its chronology, she reveals a person whose preoccupations remain consistent even as her desires and attitudes are always contradictory. It’s an archive of both sameness and multiplicity—one that suggests that the most truthful picture might come not from arranging our experiences in a straight line like paving stones, but from stacking them into odd cairns that mark the accumulation of tendencies.

Pure Colour offers a parallel image of life as something that doesn’t progress, but accrues. On a walk, Mira picks up a seashell, which reminds her that “this present moment will one day be gone, and its troubles buried beneath so many layers of living.” This is one way to relate to the future: as the time when the present will have become the past. In this formulation, it’s the past that remains primary, the gist of what we are and our only guide to ourselves. In “The Storyteller,” Benjamin presents yet another way to understand this process of lamination, as the source of the wisdom contained in art. Unlike modern writing, he argues, oral traditions took shape by the “slow piling one on top of the other of thin, transparent layers,” “the layers of a variety of retellings” through which “the perfect narrative is revealed.” By reimagining the fable, Heti adds one more lacquered coat, less to prepare the way for the next than to bring out the beauty of those already there. Thus, in Pure Colour, the problem of why to make art at the end of the world solves itself. Rather than mourning the absence of a future audience, Heti finds in our strange time a gift of material that may never be surpassed.

Nora Caplan-Bricker is the executive editor of Jewish Currents.