EARLIER THIS WEEK, I went to the opening of “Naharin’s Virus,” an hour-long piece performed by the Young Ensemble of the Batsheva Dance Company at the Joyce Theater. The dance premiered in 2001, and it’s a testament to Batsheva (and the star status of its artistic director, Ohad Naharin) that audiences continue to fill theaters at upwards of $50 a ticket even to see old work.

Naharin, subject of the 2015 documentary film Mr. Gaga, is undoubtedly a compelling figure: at once a demanding, maybe even sociopathic, taskmaster to his dancers; a beloved creative genius; and an outspoken critic of the Israeli government and the occupation. That said, there were protestors outside the theater with signs reading “Don’t dance around apartheid” and “Batsheva out of step with justice,” part of the BDS campaign to boycott Israeli artists who receive funding from the state, even those who are sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, as a measure against “white-washing” the realities of the occupation. In 2016, Naharin responded to a question about the cultural boycott with, “I often say that if boycotting my company can help the Palestinian people, I would boycott my own show, and the day we’ll have a peace treaty with the Palestinians will be the happiest day of my life.”

Naharin’s aspirational, sympathetic, but ultimately unsatisfying response about boycotts mirrors a kind of warm, human, but ultimately unsatisfying ambiguity in “Naharin’s Virus.” Or is the piece’s inexact nature precisely its point? It is, after all, an adaptation of Peter Handke’s 1966 anti-play, “Offending the Audience,” which attempts to deconstruct every artifice of theatre through word and action. One dancer in “Naharin’s Virus” serves as a kind of “Our Town” Stage Manager, a narrator who also engages in the action, speaking directly to the audience using Handke’s text and constantly reminding us of our audience-ness and our misguided expectations. One of the very first proclamations the dancer makes is, “Your curiosity will not be satisfied.” This ended up being true.

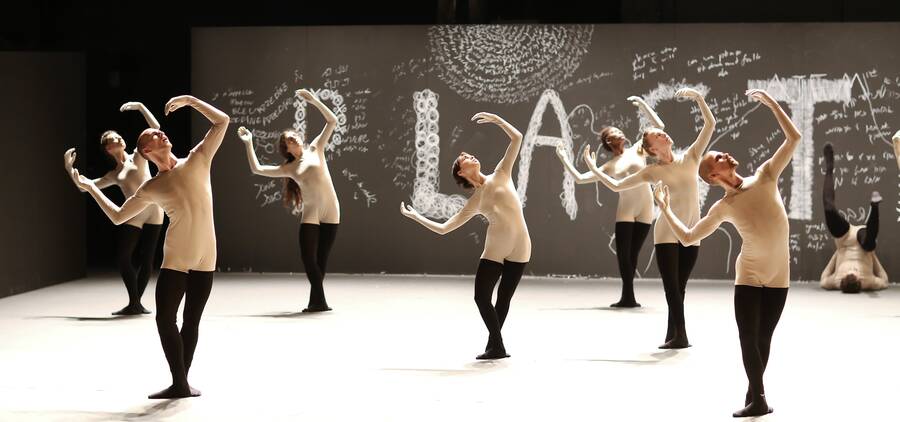

The dancers write the word PLASTELINA on a chalkboard that serves as the backdrop for the stage, which one can only assume in this context is a purposeful misspelling of the word PALESTINE. But what does Palestine have to do with this anti-narrative, anti-spectacle spectacle? At one point there is also a compelling voice-over of a woman telling an evocative story about being beaten by her mother, and, to her surprise, enjoying it—but it also left me wondering, what part does this play in the whole of the piece?

I kept thinking that the entire setup was something of a dodge, and that, unlike other performances by Batsheva I have seen, “Naharin’s Virus” ultimately lacked a cohesive drive. The piece felt like a continual gesture toward something big (the very nature of capital-A Art) and something contested (Palestine), without allowing its own instinct toward making meaning of either. I know, I know: didn’t the narrator warn us about exactly that at the beginning? But I left the theater grumpy and agitated, and it didn’t feel like a productive discomfort: I felt like I had been on the edge of release but not released. I saw that reflected in the dancers’ bodies; I felt it in my own. I felt as though I had been manipulated, as one often feels upon leaving a theater—but it was made worse by the sense that the manipulation had no object.

That the piece is thought-provoking I can’t deny. It is also, at times, fiercely beautiful: the dancers do exceptional things with their bodies, and Arabic folk music by the group Al Majad is especially memorable, lush and evocative. I was struck throughout the piece by the tension between release and control: the dancers performing feats of isolated muscle movements and the smallest of gestures, and then bursting wildly into ecstatic, liquid movement. Each time, though, that I found myself in that altered state of perception of beauty, it was cut short too soon, and I was left hanging. The most notable example of this is the closing sequence, in which you can see the dancers struggling to keep their movements small, non-dancerly, as they shuffle in repetitive circles, never again bursting into that electric movement. I know the routine is intentional, the constraint purposeful, and so I must assume that the discomfort is at least one desired outcome of the piece. And if we read that intention into it, I can make a projection about what PLASTELINA means to the piece: that we as the audience are offered no catharsis because the characters in the real life play of Palestine get none. If that’s right, though, it’s so on-the-nose as to be really, truly, boring, and even politically permissive (which I wouldn’t necessarily care about if the piece wasn’t performed, literally, against an obliquely political backdrop).

In an alternate vision, the setup could explode into discovery, as Hannah Gadsby manages in her one-woman show “Nanette,” which is a kind of anti-comedy as “Offending the Audience” is an anti-play. “Nanette,” which I saw at Soho Playhouse and which now screens on Netflix, sends the audience careening between feeling complicit and understood and back again in a dizzying and discomforting ride that comes from the specificity within the work. Gadsby evokes complex emotions and ideas and then contradicts or undermines them, and never shies away from pushing each possibility to its conclusion, while provoking a similar sense of self-awareness from the audience. Or, in the language of dance, I’m reminded of George Balanchine, whose modern (or proto-postmodern) plays on folk dances (and folk mentalities) are at once so precise, and just off-kilter enough, that they transcend their sources to create something beautiful even when they’re funny, playful, and self-conscious. It’s this level of specificity, which also yields real stakes, that is perhaps what’s missing in “Naharin’s Virus.”

Naharin definitely has a sense of humor—before the show begins, one of those inflatable flailing-tube apparatuses of the kind placed outside car washes is the sole thing on stage, beckoning to us in a truly funny suggestion of the company’s signature style. But I don’t believe that the piece is meant to be merely a setup for discomfort, or a kind of joke, the same way I don’t want to out-of-hand dismiss Naharin’s perhaps naïve or not-wholly-good-faith response to the boycott question. “You are welcome here,” Handke’s narrator (and Naharin’s dancer) tells us and retells us; but perhaps the opportunity in this adaptation was for Naharin to have explored the hyper-local and specific meanings of “welcome,” “here,” and even “you” in Israel/Palestine. That would have made for a compelling piece.

“Naharin’s Virus” runs at the Joyce Theater July 10-22.

Maia Ipp was one of the four editors who relaunched Jewish Currents in 2018. She is a writer of fiction and cultural criticism and the artistic director of the New Jewish Culture Fellowship. In 2020–21 she was a creative writing teaching fellow at Columbia University, where she also held a De Alba fiction fellowship.