When Cruelty Builds Community

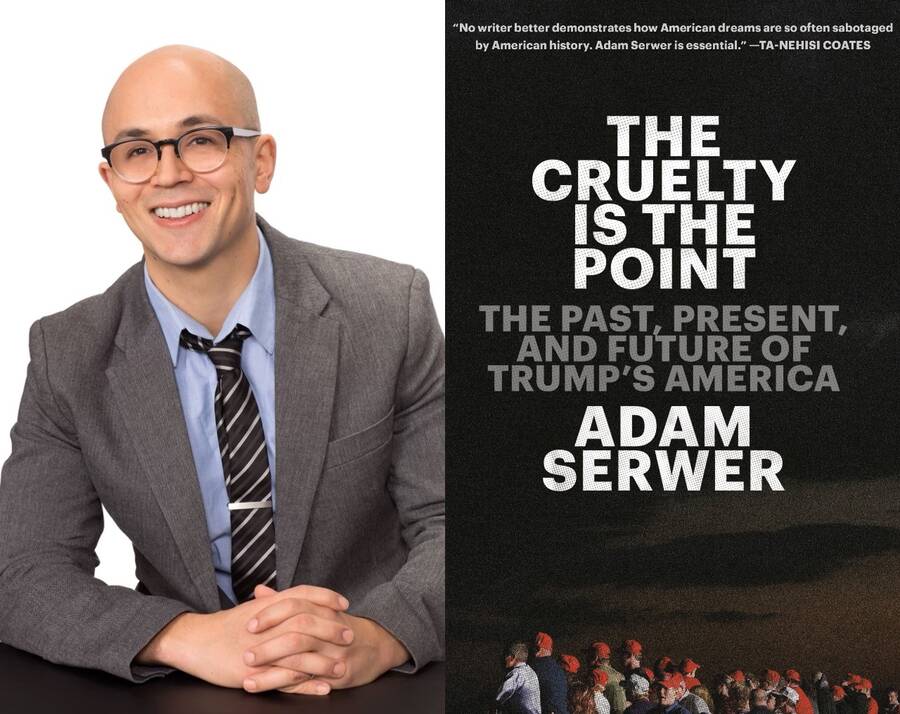

Adam Serwer discusses his collection of writings on the Trump era.

Adam Serwer, a staff writer at The Atlantic, is one of the most astute observers of the tide of nativism and hatred that powered Donald Trump’s rise to the presidency. (He’s also a fellow product of Temple Sinai in Northwest Washington, DC, which my parents still attend, and a mensch.) His essays dismantle the argument that economic anxiety determined the Republican Party’s current trajectory, drawing deeply on American history to show how white supremacy has always been integral to our political divisions, and continues to explain them now.

I recently interviewed Adam about his first book, The Cruelty Is the Point: The Past, Present, and Future of Trump’s America, released last month. It takes its title from a massively viral article he wrote in 2018, which located the essence of Trump’s appeal in his sadistic contempt for racial and ethnic minorities. The book collects Adam’s writings from throughout the Trump years, and also includes three brand new essays, two of which will be of particular interest to readers of Jewish Currents: One discusses Stephen Miller’s Jewish immigrant family background, and the other considers the American Jewish political divide over Israel. Our conversation below has been lightly edited. It originally appeared in yesterday’s email newsletter, to which you can subscribe here.

David Klion: Why was it important to you to cover Stephen Miller and intra-Jewish political divisions in new essays written specifically for this book?

Adam Serwer: When I was covering Trump rallies in 2016, I heard a lot of versions of the statement, “My family came here the right way.” It struck me that this was the cornerstone of a recurring phenomenon in American history, in which the targets of a previous generation of nativism justify their nativism against a new generation of immigrants. Since Miller was the Trump administration’s most prominent nativist, the journey of his family seemed like an appropriate way to illustrate this phenomenon. I wanted to show that while his ancestors might not be very different from the people he has spent his career demonizing, the immigration system today’s migrants face is very different.

As for the Jewish divide, it seemed clear to me that Trump, by virtue of his overt Christian nationalism and Christian Zionism, was forcing some uncomfortable realizations among American Jews about the tensions between the values they were fighting for at home and the ones they were taught to embrace when supporting Israel. I did not have the data that has recently come out showing just how broad that conversation has been, so I wasn’t able to include it, but I think that observation pans out.

One thing I wanted to do was to go back into American history and help illuminate how and why Jewish American pluralism evolved. In part, I was responding to the right-wing slander that represents this pluralism as a form of weakness or naivete, rather than a combination of pragmatism and idealism. I also wanted to show that Jewish American solidarity with other religious and ethnic minorities was a form of strength rather than weakness.

DK: You tell the story of Miller’s maternal ancestor Wolf-Leib Glosser, who immigrated from a town in the Pale of Settlement not far from where some of your own ancestors lived. You also interviewed one of Miller’s living relatives, David Glosser. What kind of insights into Miller did you get from researching this story, and why is Miller such a uniquely unsettling figure to so many American Jews?

AS: Miller is unsettling because we know he supports the ideological underpinnings of American immigration policies that led to many of our relatives, and possibly his own, being wiped out by the Nazis in the Holocaust—but he’s also willing to invoke his Jewish identity when attacking other religious and ethnic minorities in the United States, whose mere presence he regards as a threat. In one sense, Miller is as assimilated as a Jewish American can be. The predominantly liberal outlook of American Jews today stems in part from our resistance to the ideological and political journey taken by many of the descendants of late 19th-century and early 20th-century European immigrants after World War II, large numbers of whom departed from the New Deal coalition into the Nixon–Reagan one. Despite the advantages that the American color line granted to Jews of European descent, Jewish American pluralism survived because most of us continued to think of ourselves as a people apart.

Glosser is a much more familiar figure to me in that he sees the same lessons in American Jewish history that most of us see. He still works with HIAS, the organization that helped his ancestors flee oppression in the old Russian empire, even though the refugees they serve are no longer Jewish. For reasons you can read about in the story, I think his ancestors would be very proud of him. But the story is a reminder that learning those lessons is not inherent or automatic—it’s a choice we all can make or not make.

DK: In your essay on the Jewish political divide, you write that “Israel is a fact; it exists”; you go on to say that Israel’s insistence on denying Palestinians rights threatens that existence. I’m curious to hear how your own views on Israel/Palestine have evolved over time, and what you make of recent arguments, such as Peter Beinart’s, suggesting that the two-state solution is over and that Israel’s existence as we know it may not be reconcilable with progressive values?

AS: Any arrangement in which a government denies political rights to a group of people based on their racial, ethnic, or religious background, as the Israeli government currently does, is irreconcilable with progressive values. There are people on both sides who support both the one-state and the two-state options, but obviously support for a version of the two-state solution that is simply a fig leaf for further de facto annexation or oppression of Palestinians is not progressive. I have found Peter’s writing informative and compelling, but I’m not in a position to dictate what the final outcome should be, beyond saying that the occupation is unjust and must end without further bloodshed, dispossession, or displacement.

Earlier in my life I would have identified as a liberal Zionist, much as Peter did, seeing Israel as a necessary exception given the history of global antisemitism. But as an American, I do not want to live in a country where first-class citizenship is defined by race, ethnicity, or religion, so it would be absurd to demand Palestinians or anyone else accept such an arrangement elsewhere.

DK: One of the most memorable essays in the book, originally published in 2018, explores with great nuance the tortuous role Louis Farrakhan plays in black–Jewish communal relations, and includes an anecdote about your own experiences as a biracial Jew in Washington, DC, during the Million Man March. Given the upheavals in US discourse around race over the past year, as well as ongoing controversies around the definition of antisemitism and who in America is primarily responsible for it, what do you see as Farrakhan’s significance in 2021?

AS: Anti-Jewish thought is a huge part of the development of the Western intellectual tradition. As I write in a new introduction to that piece in the book, Farrakhan is a product of that tradition, even though he is rarely recognized as such because he has rearranged it into an unusual configuration: Instead of the Jews being responsible for capitalism or communism, the Jews are responsible for white supremacy. That he’s black apparently blinds people to the fact that, with all the rhetoric about shadowy financiers and cultural decadence, he sounds like a typical European right-wing nationalist.

Farrakhan’s conspiracism is no more historical, but it retains potency for the same reason that antisemitism retains potency across the political spectrum: It offers a simple explanatory frame for a complicated world. It makes less sense to argue about who is responsible for antisemitism than who is exploiting it.

As long as American policy continues to maintain an underclass largely defined by the color line, organizations like the Nation of Islam will fill the vacuum left by the state and the rest of society, and the people they help will be grateful for their presence. It doesn’t matter how many black or white leaders denounce Farrakhan. He and the Nation maintain a presence where his critics do not. As long as that remains true, he will have supporters.

DK: You write about the minority of Jews who supported Trump, but how do you understand both them and the tiny but slightly increased minority of black voters who supported Trump last year? In particular, how do you situate them in terms of your thesis that “the cruelty is the point”—in other words, that Trump draws support primarily from appeals to sadism and bigotry? Broadly speaking, do members of minority groups who found Trump’s message appealing strike you as exceptions to that thesis, or do they further confirm it?

AS: If minority voters had to wait for politicians who were not racist before exercising the franchise, they would vote a lot less often. In 1932, the Democratic Party was the party of Jim Crow. Nevertheless, black voters in the North supported Franklin Roosevelt because he had an economic agenda that would benefit them, and because the Republican Party had all but abandoned them. That didn’t turn James Eastland into Martin Luther King Jr. The fact that Trump won more support from voters of color in 2020 than he did in 2016 is a political challenge for the Democrats, but it doesn’t change what he believes, what he did, or what he stands for. If Democrats don’t want Republicans to win over those voters, they have to take a lesson from the GOP of the early 20th century and not assume the rival party’s racism will keep minorities in the Democrats’ tent.

The book also describes how cruelty can be a tool for building and defining communities, and how acceptance and membership in such a community can be a powerful motivator of human behavior. This is not a Trumpian invention; it goes back to the founding itself. If you declare that “all men are created equal,” but you really mean “white men with property,” you have to figure out a framework for explaining why, for example, the human beings you own as chattel are not entitled to the rights you have just described as inalienable. It would be foolish to assume these appeals only work on white people, because part of how this functions is that new lines can be drawn that offer belonging to people who in other contexts would be excluded—for example, the abolition of property requirements for white male voters in the early 19th century in the North was often paired with black disenfranchisement. This is just one way capital has divided America’s multiracial working class since the colonial era. It’s important to remember that none of this began with Trump, and it’s not going to end just because he was defeated.

David Klion is a writer and a contributing editor at Jewish Currents.