“What does Vietnam have to do with Tisha B’Av?”

Most Jews who observe Tisha B’Av spend it mourning in synagogue. In 1972, this group spent the holiday in the streets—presaging today’s era of political ritual.

ON THE HEBREW CALENDAR, Tisha B’Av, the ninth day of the month of Av, is the date in which Jews have mourned the destruction of the second temple and the exile of the Israelites for 2,000 years. On this day it is customary to fast and to give to charity; some go as far as to dress in all black. Traditional observance of Tisha B’Av is a profound reflection on thousands of years of displacement, usually spent in synagogue. But on Tisha B’Av 1972, a group of young Jews gathered outside of the Federal Building in downtown Chicago.

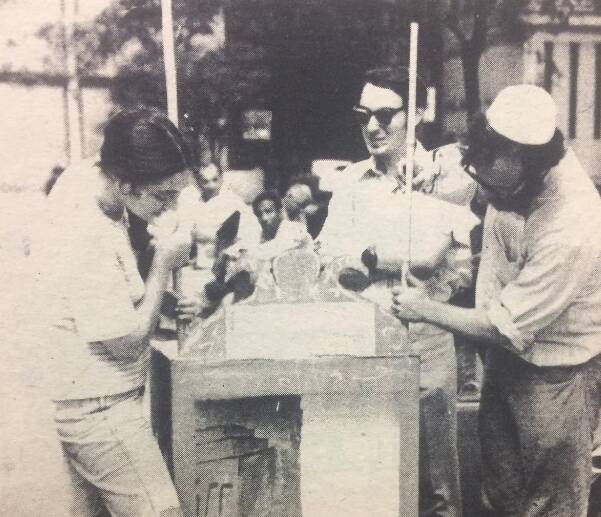

The group was made up of members of the chavurah (independent Jewish religious community) Am Chai, and the Chutzpah Jewish Liberation Collective, a leftist political group that published a newspaper. Most covered their heads with kippot. Like many Jews all over the world that day, they were fasting. What made this different was that they were not at home or at temple, but rather on the street for the entire day and night. And they weren’t just fasting to mourn the destruction of the Second Temple in ancient Jerusalem. They were also protesting the Vietnam War.

In Chutzpah, the newspaper of the collective, they publicized the Tisha B’Av action:

Over and over, people asked us the same question: what does Vietnam have to do with Tisha B’Av? What does it have do with Jews as Jews? Most of us had to deal with that question at least once, and found ways of answering. We have been victims of foreign domination, racism, genocide, and apathy—for our own security all these things have to end.

On the steps of the Capitol, a Washington DC based chavurah, Farbrengen, protested the war with Jewish ritual as well, in coordination with Am Chai. The experience in DC was recorded in Chutzpah along with the longer report in Chicago, which explained why they were specifically protesting the Vietnam War on the holiday of Tisha B’Av:

We are commanded to do justice and to love mercy. And not to follow a multitude to do evil. We mourn the destruction of a temple and a nation 2000 years ago, and we cannot now ignore the thousands of temples and the nation being destroyed with our money, in our name. We were told that our public stand as Jews against the war would endanger Jews, and that we should stick to a little Jewish food, a little praying in shul, and a little charity. We answered that to be Jews just on those terms would really endanger our survival as people.

What came of it? Some of us are working with the Indochina Peace Campaign right now, or finding other ways to work against the war. Many of us are involved in the McGovern campaign. For us, Tisha B’Av was a strengthening experience. For our fellow Jews of Chicago, we hope there was, at least, a renewed awareness of the bond between the Jewish people and all peoples who have experienced exile and suffering.

In the early 1970s, many Jews were still organizing within the ranks of the atheist far left. But these chavurot, fasting and protesting on the street, connected an emerging Jewish identity politics in which leftist struggle was blended with Jewish prophetic tradition.

In the Chutzpah reportback from the action, the activists cited the incredulous questions of some of those who observed them. To a contemporary progressive Jewish reader, the idea that a protest centered on Jewish ritual would raise eyebrows might seem strange. But at the time, the mashup of religious ritual and leftist action was an innovation. Along with the famous Freedom Seders of the late 1960s, these rituals signaled a change in the methods and meanings of Jewish public protest. More and more, Jewish ritual became the medium through which organized Jews expressed their progressive politics.

Despite the questions thrown at these young Jewish activists while they fasted, protested, and prayed, their approach would be validated in the decades to come. In the 1980s, the New Jewish Agenda staged national protests on Tisha B’Av to protest nuclearization, memorialize Hiroshima and Nagasaki Day, condemn the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and many other examples. Decades later, young Jewish activists continue to turn toward Jewish ritual for inspiration and sustenance as they call for immigrant rights, an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land, and racial justice in the United States. In recent months, Jewish activists across the United States publicly recited the Mourners Kaddish for the Palestinians murdered by IDF snipers at the Gaza border protests. Rabbis and religiously identified Jews were arrested in the US capitol in protest of the decision to rescind DACA. These actions are part of a tradition connecting them to the Tisha B’Av protest outside of the Federal Building in Chicago.

While Am Chai is still around today, Chutzpah disbanded in 1981. For a decade, the collective would continue to creatively disrupt the Jewish establishment and the leftist political scene. The collective’s activism would take them to Palestine, Israel, and outside of the Soviet Embassy and the Israeli consulate, as well as into the files of the Chicago Police Department. Many of the members would go on to help form New Jewish Agenda and raise money for Peace Now, as well as continue their tireless activism on behalf of the Chicago Teachers Union, women’s liberation, LGBT rights, public health, and progressive local politics. Two would go on to become rabbis. As we blend Jewish ritual with our political consciousness, especially when we find political voice through the sacred act of mourning, we should honor the radical Jews of the previous generations who walked this path before us.

Isaac Brosilow is a contributing writer for Jewish Currents and an independent researcher from Chicago, currently based in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Protocols and Graylit.