“Three More Pieces”

“I don’t recall that those colorful brochures from Israel, sent to Russian Jews like my family, mentioned the Palestinians.”

MAY 14th, 2018 played out as on a split screen: the Palestinian dead on one side and the celebratory opening of America’s embassy in Jerusalem on the other. Palestinians in Gaza had been protesting for weeks by then, with the biggest day of protests planned for May 15th, the 70th anniversary of the Nakba. But with Donald Trump’s intentionally provocative decision to move the embassy to Jerusalem and to open it on May 14th—the 70th anniversary of Israel’s declaration of statehood and US President Harry Truman’s recognition thereof—the main Gaza protest shifted to a day earlier. Everyone involved knew what was about to transpire, with ample time to get ready for the inevitable outcome. The split-screen images playing out that day were hardly a product of chance: multiple actors and antagonists had conspired for the events in Gaza and Jerusalem to unfold simultaneously. On one side, the celebration in Jerusalem, with Donald Trump’s family representing America on the world stage like unappointed royalty. On the other, the massacre in Gaza.

These images playing out side by side are rife with symbolic value, to which people on all sides of the political spectrum are already laying claim. For me, this coupling of images prompted a different set of screens to play out in my mind.

My first screen:

Like that of pretty much any Soviet and Russian Jew, my Zionism—or whatever passed for it—was reflexive and uncritical. I grew up in Russia in the 1980s and ‘90s, at a time when the Soviet Union opened its borders and Jews, who had been prevented from leaving the country until then, began to move to Israel en masse. My childhood was defined by a certainty that Israel—where most of my relatives and friends resettled by the time I turned 13—was where we, too, were going to live.

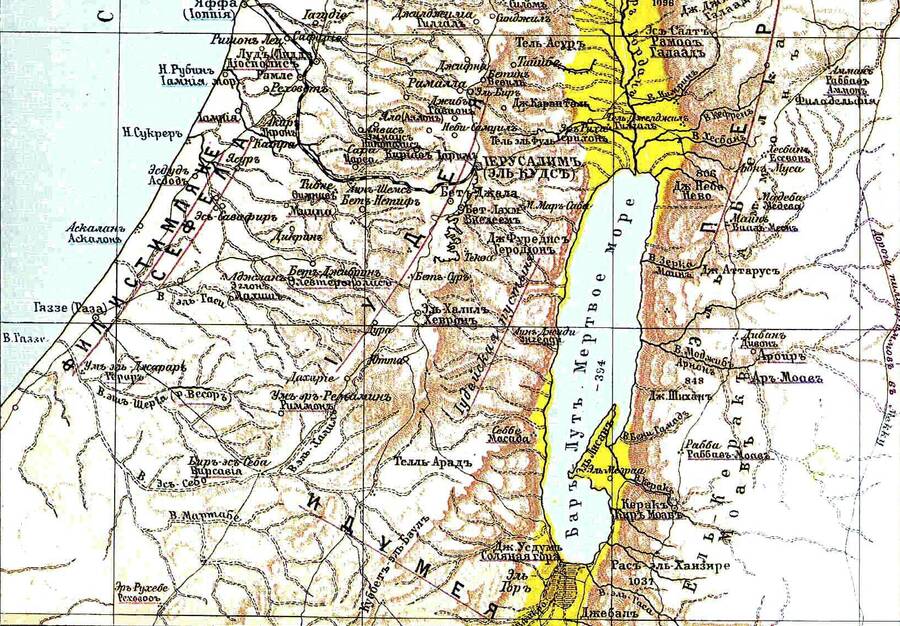

Colorful brochures from the magical country made their way to my faraway and colorless industrial hometown in the Urals. For my final project in my 8th grade geography class, I cut out pictures from some of those brochures and glued them into a thick notebook—a report on the foreign country of my choosing. The content of that final project was what I would later recognize as plagiarism: everything I wrote in that notebook, I copied word for word from those very same glossy brochures encouraging Aliyah (immigration or, literally, “ascent” to Israel) for my kind. But that’s what we were regularly expected to do when it came to such homework in Russian schools, so I didn’t question it at the time.

I don’t recall that those colorful brochures from Israel, sent to Russian Jews like my family, mentioned the Palestinians.

When the time came to turn in my work I remember feeling a giddy sense of pride about the country I knew I would surely be moving to soon. I was an avid stamp collector then, so this giddiness must have been mixed inextricably with a provincial post-Soviet child’s excitement about handling stamp-sized colorful pictures of exotic flowers, sun-drenched cityscapes, and the sea.

I remember feeling blindsided, around the time I turned 14, when my parents began telling me and my sister that we would likely be going to America instead. This was disappointing. I didn’t have the kinds of warm feelings—or familiarly warm images in my imagination—for America that I had for Israel. My grandfather had traveled to America in the late 1980s to reconnect with a long-lost relative. He brought back hand-me-downs from this unknown American family, and various odds and ends he picked up at garage sales. I found a piece of licorice candy in the pocket of an old pair of jeans; it tasted unfamiliar and disgusting.

My second screen:

I recall distinctly when this reflexive Zionism of my childhood—or whatever it was that passed for it—was first irreversibly shaken. While I was a graduate student, I spent the academic year of 2008-2009 in West Jerusalem. My Hebrew had gotten quite good. I spent the first night of Hanukkah that year at someone’s party near the President’s residence in Rechavia. There, one of the guests taught me a Hanukkah song I hadn’t heard before, a song in a minor key about a “sevivon mi-oferet yetzukah,” a dreidel made of cast lead.

A few days later I was visiting a family of eminent Russian Israeli cultural figures for breakfast at their home in a different part of the city. Hamas had been shooting rockets from Gaza for a while by then and, in response, a military offensive euphemistically dubbed “Operation Cast Lead” (I now knew exactly the meaning of the term) had begun earlier that morning. Before I left the house, the news announced that Israeli forces had bombed a police graduation, killing several dozen of the graduating men and members of their families. In the process of feeding me a lovely breakfast, the eminent Russian Israeli cultural figures—of the self-consciously logocentric sort—would turn on the radio on the hour to listen to news updates in Hebrew. After each newscast, one of them would gleefully report the latest death toll to the other and to me in Russian: “O! Nu vot eshche tri shtuki!” [“Aha! Three more pieces!”]

I had done quite a bit of reading on the Holocaust by then, mainly in college, mainly because I was taken in by my college professor’s work and pedagogy on catastrophe and memory. A scholar and teacher of literature, my college mentor made me aware of language, including the language of violence and dehumanization, together with the precision and dangers of its use. So, I knew that morning that the Russian word, “shtuki,” which the eminent Russian Israeli cultural figures were using to discuss casualties in Gaza, was a borrowing from the German “Stück” (plural, Stücke)—a word that bureaucratically-minded Germans used to refer to the numbers of Jewish dead during the Holocaust.

I am not ready to turn this split screen of associations, prompted by the tragic and violent events of May 14th, 2018, into any one fully-fledged political statement or affiliation. I am hardly the only Jewish person grappling with such thoughts at the moment: the events of this week have prompted many Jews around the world and, particularly in America, to question their allegiances—both for the first time for some and for others, like me, not for the first time at all. These reflections are idiosyncratic by necessity and by definition, and as such, they are likely to be drowned out by much better-organized choruses, ready to cast these personal tidbits into any number of readymade molds. But, at least for now, I need to keep watching my own split screen of associations play disturbingly on a loop.

Sasha Senderovich is the author of How the Soviet Jew Was Made (Harvard University Press, 2022). With Harriet Murav, he co-translated David Bergelson’s novel Judgment (Northwestern University Press, 2017). He is an assistant professor of Slavic, Jewish, and International Studies at the University of Washington, Seattle.