Revolutionary Bandits

A new history of the revolutionary criminals who rejected any possibility of revolution coming from the degraded masses—and turned their revolt into an individualistic one.

Discussed in this essay: Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits: The Crime Spree that Gripped Belle Epoque Paris, by John Merriman. Nation Books, 2017, 327 pages.

FRENCH ANARCHISM, so important in the history of leftwing politics, giving the world Louise Michel and Sébastien Faure and providing a home to so many exiles, was also a main locus of two of anarchy’s more ambiguous moments: the bomb-throwing “propagandists of the deed” of the early 1890s, and the wave of crime that went under the name illegalism in the late 19th to early 20th centuries.

The darkest, most controversial moment in this history was the murder-and-crime spree of the gang of individualist anarchists that came to be known as the Bonnot Gang. Their murders, attempted murders, and holdups froze the country’s attention in 1911 and 1912. These revolutionary criminals, the sources of their activity, the society in which they moved, the ideology that drove them, and the ultimate fate of their band and movement, are the subject of the Yale historian John Merriman’s fascinating, lucid, and evenhanded Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits.

Merriman has developed a niche, writing about some of the most interesting and controversial periods in French revolutionary history, including the propagandists of the deed in The Dynamite Club, the Paris Commune in Massacre, and now the Bonnot Gang. In every instance he has brought to his books a depth of knowledge, a well of understanding if not sympathy, and a fluid writing style that is peerless.

The Tragic Bandits, as they came to be romantically known, were a product of fin-de-siècle France, its exploitation and its inequality. (Merriman correctly rejects the use of La Belle Epoque as a name for the era, one that was “belle” for just the privileged few. Unfortunately, the publisher failed to get the message and included the banished term in the subtitle.) If some joined the growing socialist movement in order to change France, while others became communist anarchists or anarcho-syndicalists, there were others -- equally horrified by the France they lived in, where too many of the exploited seemed to be accepting their lot -- who rejected any possibility of revolution coming from the degraded masses and turned their revolt into an individualistic one. If for some this meant simply the cultivation of the self intellectually and morally, for others this tipped into hatred of everyone implicated in the continuation of an unjust order, which came, in effect, to include virtually everyone.

Hating the law as a fundamental interference with their liberty, hating capitalism for its immiseration of the workers, hating the workers for going along with the order of things, a hardcore group of individualists adopted crime as the ultimate form of revolt. If for some, like the first of the great anarchist bandits, Marius Jacob, banditry was an updating of Robin Hood, with only the wealthy robbed and the takings tithed for the anarchist cause, for others crime was a good in and of itself, and if bystanders were killed or wounded in the process — well, that’s what they got for not rebelling.

JULES BONNOT and his comrades were among this latter group. A mix of Frenchmen and Belgians, they were men and women -- for women play an important part in this tale, as they did in all elements of the anarchist movement in France at the time -- who took their ideas to the extreme. “Science” was their guide, so much so that the Belgian Raymond Callemin was known as “Raymond La Science.” Purity of ideas was not enough; they also had to be pure in body, and abhorred salt, oil, vinegar, coffee, and tea, and ostracized those among them, like Victor Kibaltchiche -- the future Victor Serge -- and his partner Rirette Maitrejean, who consumed those impurities. Though Merriman never mentions it, exercise was an essential part of their daily routine, and when they were later put on trial for murder, their exercise equipment was displayed in the courtroom.

This demand for purity went hand in hand, in a perverted way, with their crime spree, which flowed from their beliefs.

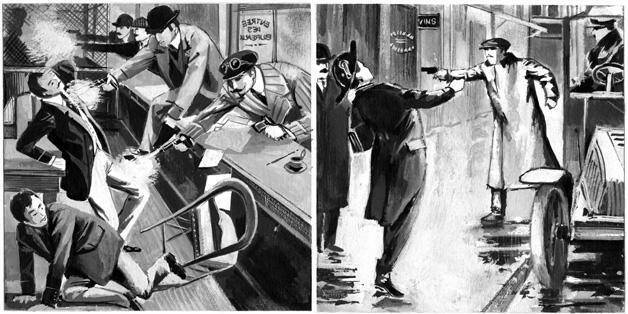

It began with the shooting of a bank courier of the Société Générale on December 21, 1911, the theft of cash and securities, and the flight in an automobile -- the first time a car had been used in a hold-up in France. The spree would continue through a series of increasingly shocking and shameless acts: the murder of a rentier and his maid, the shooting and killing of police on their trail, the theft of weapons . . .

Here was illegalism in its most direct and brutal form, and the reaction among other anarchists varied, though not as widely as one might think. The right to asylum, as the anars called it, led many to provide the fleeing bandits with shelter. Agreement with their acts mattered not; they were anarchist comrades and as such were provided support.

If some anarchists saw the illegalists as harmful to the anarchist movement, many, among them the best known among them, wrote in support of the Bonnot Gang and illegalism. André Lorulot would write of illegalism that it was “the permanent and reasonable response of the individual to everything that surrounds him -- it is the affirmation by each person of his own existence and his desire for complete development.”

Some solid police work and a fair amount of reports by informers allowed the police to arrest most of the gang members, though the leader Bonnot and two of his confederates were the last on the loose. Bonnot, his hiding place discovered, killed the deputy head of the security forces and fled to a garage in Choisy-le-Roi, where he and a friend who had hidden him held off hundreds of police for hours before being killed. He left a note that was a perfect expression of the illegalist mindset: “I have the right to love. Everybody has the right to live and because your imbecile and criminal society intends to get in my way, too bad for you all.”

The final bandits on the loose, Octave Garnier and Rene Valet, were also tracked down and also fought off hundreds of police and even soldiers in Nogent-sur-Marne. Their dramatic deaths almost overshadowed their sordid acts, and the legend of the Bonnot Gang was well launched.

But the movement they represented went into precipitous decline. Not only illegalism, but individualist anarchism slid into relative insignificance, despite the brilliance of many of its leading lights, men like Han Ryner, Mauricius, Hem Day, and Emile Armand.

THE 1913 TRIAL OF ILLEGALIST ANARCHISTS, which resulted in death sentences for three of them and long prison terms for three, as well as the imprisonment for a full five years of the man who would be Victor Serge -- guilty of possession of stolen guns -- was their final hurrah. Merriman does not cover the trial extensively, and leaves out a significant tale, the argument during the trial between the former comrades Lorulot and Kibaltchiche, the latter demanding to know why he was on trial while Lorulot freely walked the streets of Paris. This undignified moment tends to get elided from accounts of Serge’s life.

Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits is marred by signs of sloppy editing: among others, the title of Marcel Proust’s masterpiece in French is given incorrectly; the name of one of Bonnot’s confederates, Jean De Boë, is given without the umlaut; the names of the cities of Basel and Antwerp are given in French, not English; and the Belgian anarchist Hartenstein is apparently put on trial after being killed.

Factual errors also creep in. The most notorious of French anarchists, Ravachol, is said to be Dutch-born, when he was in fact born in France, and throughout the book the individualist anarchist newspaper l’anarchie is called L’Anarchie. This might seem a minor peccadillo, but it is not: the founder of the paper, Albert Libertad, very pointedly spelled the name without majuscules, granting all its letters absolute equality.

More importantly, the great Victor Serge, at the time still Victor Kibaltchiche and writing in the anarchist press as Le Rétif, is a central character and commentator on the action, and throughout the book, Merriman accepts Serge’s self-exculpatory self-characterizations as expressed in his classic Memoirs of a Revolutionary. Merriman writes, for example, that “Victor’s philosophy was neither that of the illegalists nor that of the dominant individualists.” In fact, any reading of Serge’s writings in l’anarchie (many of which can be found in this author’s Anarchists Never Surrender) shows that all of the classic themes of individualist anarchism appear there -- his contempt for the cowardly masses, his condemnation of what he called “the revolutionary illusion,” his insistence that only change within individuals will ultimately lead to real change, and, most importantly, his defense of illegalism and those who fought the cops. Serge maintained all of this right up to the time of his arrest, and Merriman’s footnotes even include an article that contains a talk Serge gave in defense of anarchist bandits almost immediately before his arrest. That he later sincerely grew to hate illegalism and the illegalists is certain, but the evidence is that it was the fruit of post-arrest reflection.

Merriman similarly gives Serge a pass for his early years in Soviet Russia, stating that Serge opposed the Cheka and the government’s crushing of the Kronstadt Uprising. Serge, in fact, admired Cheka founder Feliks Dzerzhinsky as an honorable revolutionary, and defended harsh measures against counter-revolutionaries as an unfortunate necessity, although he later did come to see the Cheka as a fatal error. He also privately condemned Kronstadt, but wrote articles in the international Communist press defending it. (For a full analysis of Serge during this period, see this author’s “Victor Serge und der Anarchismus: Die russissche Jahre” in Philippe Kellermann’s Anarchismus und russische Revolution.) In the same way, in private conversations with visiting anarchists, Serge spoke of the new Soviet state as a horrific dictatorship while writing calls for anarchists to actively support the Soviet state. His conduct in these regards led to Serge’s being called l’homme double in a recent anarchist account of his life.

Ballad of the Anarchist Bandits, incidentally, is not the only book on the topic. Richard Parry’s 1987 masterpiece, The Bonnot Gang, has recently been reissued by PM Press. Given that publisher’s poor distribution, it will not be readily found in bookstores, but is worth the effort to track down. No book covers the Bonnot Gang and its time as thoroughly as Parry’s, but Merriman’s is a worthy second.

Mitchell Abidor, a contributing writer to Jewish Currents, is a writer and translator living in Brooklyn. Among his books are a translation of Victor Serge’s Notebooks 1936-1947, May Made Me: An Oral History of My 1968 in France, and I’ll Forget it When I Die, a history of the Bisbee Deportation of 1917. His writings have appeared in The New York Times, Foreign Affairs, Liberties, Dissent, The New York Review of Books, and many other publications.