The Rise and Fall of the Coops

The Bronx cooperative was a communist utopia, until it wasn’t.

AT THE TURN OF THE 20TH CENTURY, the northern edge of the Bronx—which now includes some of the poorest neighborhoods in New York City—was dotted with the grand estates of Gilded Age capitalists. By the 1920s, however, the villages of the Bronx had been incorporated into the growing city of New York. Hoping to attract real estate speculators, the city extended subway access to the area and opened it to development.

Between 1926 and 1929, thousands of working-class Jewish city residents, many living in slum conditions on the Lower East Side, pooled their money and built large cooperative developments in the Bronx. Labor Zionists built the Farband Houses, Yiddish preservationists built the Sholem Aleichem Houses, and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America—a union led by Abraham Kazan, a social democrat who would go on to become New York’s most prolific cooperative developer—built the Amalgamated Houses. “In the late twenties,” Calvin Trillin quipped in The New Yorker 50 years later, “a Jewish garment worker who wanted to move his family from the squalor of the lower East Side to the relatively sylvan North Bronx could select an apartment on the basis of ideology.”

The most storied of the Bronx Jewish cooperatives sat just east of the borough’s botanical gardens, in the Allerton neighborhood. The United Workers Cooperatives, better known as the Coops (rhymes with “stoops”), were established in 1927 by the United Workers’ Association (UWA), a cooperative labor organization affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World and composed largely of Yiddish-speaking communists in the garment industry. “We want to build a fortress for the working class against its enemies,” the group proclaimed in a 1925 advertisement in the New York Yiddish dailies. Seven hundred families chipped in to build a sprawling apartment complex spanning two full city blocks; it featured common kitchens, social halls, and an approximately 20,000-volume library catalogued by two librarians. The Coops were unique among the Bronx cooperatives in their revolutionary spirit. Residents saw their home not just as an apartment complex, but as a forward operating base for the communist movement. “[T]hese New York Jewish Communists,” Vivian Gornick wrote in her book The Romance of American Communism, were “a nation without a country, but for a brief moment, a generation, they did have a land of their own: two square blocks in the Bronx.”

But the radical commitments that gave the Coops their aura almost stopped the development from being built in the first place—and pointed toward its swift demise. The UWA formed in 1913 in order to buy a ten-unit apartment building in East Harlem, where members lived communally and ran a restaurant and a library; they also bought a large tract of land near the upstate town of Beacon and started Camp Nitgedaiget, where striking workers could spend the summer for $15 a week. Inspired by their success, some workers in the UWA proposed that the group establish a full-fledged cooperative housing complex. The communists in the group were initially skeptical. How far could such a project really go under capitalism? Could a housing complex organized around communist ideals endure in a commodified real estate market without negotiating on its principles? Despite these questions, the enthusiasm among UWA members for large-scale cooperative housing was so great that the communists ultimately embraced, and came to direct, the project, as a radical effort—social housing as a weapon in the class struggle, rather than simply a road out of poverty for members. It survived for 16 years.

WORKING-CLASS TENANTS in early-20th-century New York faced an ongoing crisis. Housing was a barely regulated sector of the American economy, and developers constructed tenements as cheap, dirty investment schemes that lured in workers who had nowhere else to go. The apartments they built were filthy, dilapidated, overcrowded, overpriced, prone to fire, and ridden with tuberculosis and flu. Tenants regularly fought “rent wars” with their landlords, striking, picketing, and denouncing non-participating neighbors as scabs; the large, restive Jewish immigrant population of the Lower East Side was at the heart of the movement. At the same time, middle-class progressive reformers seeking to improve the lot of the urban poor lobbied for building code legislation and encouraged philanthropists to build better housing for workers—but these efforts did not always work to the benefit of tenants. As housing became more regulated and thus more expensive to build, developers responded by building homes for the wealthy. The working poor went from suffering in substandard housing to fighting to be housed at all.

The prospect of cooperative housing offered workers a different path. The UWA decided to create a large-scale cooperative in 1925, taking out ads in leftist papers like the Daily Worker and the Morgn Freiheit inviting all workers to join them; membership was restricted to anyone who “earned their living by the sweat of their brows.” They borrowed a cooperative housing model from Finnish immigrants who had created a development in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Sunset Park called Alku (“beginning,” in Finnish); Alku, in turn, was based on a set of guidelines for cooperative ownership known as the Rochdale Principles. Devised in 1844 by a British cooperative association called the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers and widely adopted in Europe, the principles—still used by non-speculative housing co-ops today—allot each resident one share and an equal voice in collective decision-making. If a shareholder wishes to move, they can sell their unit back to the building association at the same price at which they bought it. Membership is open to anyone. In addition to these principles, the founders of the Coops made a promise: No one would be evicted from the complex, and the price of rent would not be raised.

The workers who fronted the money for the Coops wielded significant influence on the development’s design. Each building took up only half its lot, allowing space for a plant-filled courtyard. Visitors from around the city came to admire the ivy-covered brick walls, bountiful gardens, and stone pools filled with goldfish and water lilies. Inside, floor plans were built to mimic an English university residence hall, grouping small numbers of apartments around separate entrances and stairwells to fashion a measure of privacy lacking in the “promiscuous” tenements. The Coops supported cooperative services in and around the buildings: butcher shops, groceries, a laundromat, and a tailor. They planned development of a cooperative medical care center in coordination with a local doctor sympathetic to their movement.

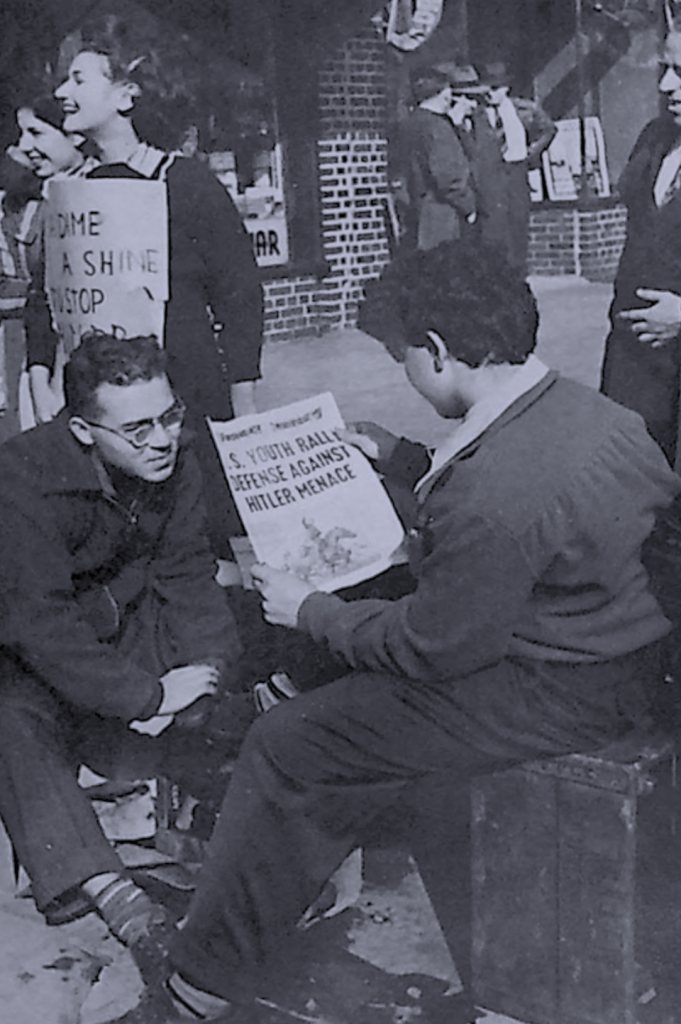

Working mothers were given particular consideration during planning and construction. Coops women helped found a kindergarten with hot meals (perhaps the first such institution built into an apartment building in US history) and—as a resident named Whitman Bassow recalled in a 1977 letter to his daughter—“an informal nursery” where children could come for meals and after-school snacks of “milk and cake.” Kids took dance, boxing, and Yiddish lessons; P.S. 96 opened nearby after Coopniks (as building residents were called) organized a campaign for New York City to build them a school. Pete Rosenblum, 93—who was born, like the Coops, in 1927 and has served for decades as the development’s informal historian—remembers kids building snowmen with the face of Lenin and collecting cigarette cartons for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the battalion of American volunteer soldiers who fought Franco’s army in Spain, to turn into bullets. “It was the biggest family I ever belonged to,” one unidentified Coopnik recounted in a 50th anniversary book about the development. “We had everything a working family could need or want . . . it was a dream that came true.”

Coopniks tried to expand that family in solidarity with the Black struggle for justice. The board explicitly reserved apartments for Black families facing systemic housing discrimination, and residents picketed facilities that discriminated against people of color, such as the nearby Bronxwood Pool. Angie Dickerson, a Black radical tenant organizer, freedom fighter, and senior member of the Civil Rights Congress, along with her two brothers Bill and Richard Taylor, lived for decades in the complex, where she received visitors like W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson; Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, a militant black nationalist, union organizer, and active member of the Communist Party lived there in the late 1940s. There were tensions over the Coops’ level of commitment to racial inclusiveness: Some Coopniks claimed that actively pursuing integration would dilute the development’s Yiddish culture, and the complex remained overwhelmingly inhabited by Ashkenazi Jews. But despite this resistance, said Steven Payne, an archivist at the Bronx County Historical Society, the Coops were “one of the most remarkable moments of intentional, militant interracial solidarity in the borough, and probably in all of New York City.”

From the outset, the ideologically charged atmosphere of the Coops “created a sectarianism beyond belief.”

This attempt at working-class unity was short-lived. From the outset, the ideologically charged atmosphere of the Coops “created a sectarianism beyond belief,” a former resident named Babe Polansky wrote in the anniversary book. Some splits concerned major questions of politics and identity. Arguments about Communist Party affinity divided friends and families, particularly after Joseph Stalin signed a nonaggression pact with the Nazis in 1939 and rumors flew of Jewish pogroms. Other conflicts, however, grew out of the day-to-day difficulties of sustaining a large radical cooperative in a capitalist country. The development’s cooperative services, like the grocery and laundromat, were quickly priced out by neighboring stores, which paid workers less than the union wages afforded to the cooperative workers; their attempt at a medical co-op never even took off. “People went for bargains,” Bella Halebsky wrote in the 50th anniversary book, and some residents “just didn’t grasp the principles of cooperative living.” Ideological divisions took shape over issues like the development’s shared electric meter (residents who wanted to maintain the collectivized billing structure called those who wanted to dismantle it “individualists”). The Coops’ material challenges, and the conflicts they engendered, became more daunting when the economy collapsed spectacularly two years after the complex opened its doors. Residents lost their jobs and left the UWA with two million dollars of unpayable mortgage debt. The Coops’ no-evictions policy, and its use of empty units to shelter families evicted from privately owned buildings, deepened the debt further.

The stock market crash also created new opportunities for state repression of the Coops. The complex regularly found itself under FBI surveillance, as well as more mundane repression by the New York political machine: When an insurgent socialist party called the American Labor Party started winning local elections, the state legislature divided the former 6th Assembly District at Britton Street, splitting the Coops in half in order to split the socialist vote. In response to the Great Depression, the federal government bought and refinanced one million mortgages across the US. Appraisers were sent around the country to grade neighborhoods on their credit risk, basing their judgments on quality of housing, neighborhood amenities, and—infamously—ethnic and racial makeup. (The term “redlining” comes from the color chart the appraisers used as a grading system.) The Allerton area was deemed “Type C” and outlined in yellow, which signified that an area was “declining.” The report cited detrimental influences such as the neighborhood’s “communistic reputation.” Lenders were encouraged to be conservative.

Thanks to a New York state moratorium on foreclosure, the Coops staved off collapse for a decade, remaining a haven for working people during a period of widespread unemployment. But by 1943, as war spending lifted the economy, the state government rolled back the moratorium and the Coops’ directors had to negotiate new terms with their mortgage lender. The two sides came to a provisional agreement that required an increase in monthly payments: one dollar more per room, per month—a significant but not overwhelming amount by the standards of the time. But before the increase could be enacted, the directors required approval from the rest of the Coopniks.

The monthly increase came to a vote one night in the auditorium in 1943. A fiery debate ensued. Some members argued that workers could not afford such increases; others claimed that a rate increase at the Coops would give nearby landlords the license to raise rents as well; still others argued passionately to save their collective ownership stake. “One of my friends, he got up and argued to raise the rent,” Rosenblum recalled. “They booed him, so he made like he was mooning them.” The vote was close, but the rate increase could not garner majority support. As a result, the Coopniks lost control of their home. Later that year, the mortgage company sold off the property to a private landlord, the Bx Corporation.

THE COOPS gradually withered away. At first, even under private ownership, the complex maintained its identity and its institutions remained vital to the community; the library, for instance, became the first organizing headquarters for the first senior citizens club in the northeast Bronx. As tenants, they launched a rent strike against Bx Corporation in 1949. In the Cold War period, however, the Coops became vulnerable to a new wave of anti-communism. “The Lenin busts went into the garbage because they thought the FBI was coming,” Rosenblum said.

At the same time, the better conditions and pay won by radical garment unions a generation before depoliticized many workers. Children radicalized in the Coops’ gardens and basements mostly became professionals and moved away. By the 1970s—as large swaths of society were privatized and the federal government sharply reduced funding for large-scale housing projects—the remaining Coopniks had grown older and their needs had changed. Some left for the Long Island or New Jersey suburbs. The development of Co-Op City in the northeast Bronx, a sprawling high-rise complex offering air conditioning and elevators less than three miles from the Coops, was especially attractive to seniors. Many Coopniks moved out and “the spirit was lost,” as Pete Rosenblum said. Today, the Coops live on in the progressive Jewish imagination. In 2009, PBS released a documentary about the Coops called At Home in Utopia, while in 2013, author Jonathan Lethem published Dissident Gardens, a book about leftist co-op tenants in Sunnyside, Queens. In an email to Jewish Currents, Lethem says that the Coops functioned as a “research ghost,” which inspired the book’s narrative.

Could the Coops have saved themselves? When pushed to relax their policy against rent increases, could they have bent instead of broken? It’s easy to see the project as the victim of its own inflexibility, as some former residents do. The Coops’ demise holds “lessons for today,” said Sylvia Manheim, 95, who was 18 when the Coopniks lost ownership of their complex, in an interview. “People should learn how to negotiate and listen more carefully, and not be so dogmatic.” And indeed, Abe Kazan’s Amalgamated Houses, which displayed a greater willingness to work with the powers of state and capital from the outset, is the only complex among the Bronx Jewish cooperatives of the 1920s to remain cooperative today. Kazan was not just willing to play ball with capitalism, but proved to be particularly adroit at it. By successfully negotiating with figures like the immensely powerful city planner Robert Moses, he went on to build more than 25,000 units of worker housing through the creation of complexes like Penn South, in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, and Co-Op City. Working from the model he established, labor unions built two dozen cooperative housing complexes in New York City. These co-ops provided democratically-governed affordable housing for workers and maintained an impressive array of cooperative services from child care centers to sports teams to credit unions.

“Everyone knows the word ‘co-op’ is a synonym for ‘Jewish housing,’” the influential Puerto Rican Bronx political operator Herman Badillo said in 1988.

But this measure of autonomy for some workers came at a cost for others. Unions typically acquired land by bulldozing slums, which meant building homes for unionized workers through the displacement of more marginalized—usually non-white, non-union—workers. Despite the Rochdale Principles’ commitment to open membership, many were segregated, and remained so informally even after the passage of laws against housing discrimination. In the 1970s, a group of Hispanic and Black homeseekers sued Coop Village, a string of union-owned complexes Kazan built on the Lower East Side, for housing discrimination; at the time, the complex was at least 90% Jewish. (The parties reached a settlement agreement and a judge later ordered Coop Village to pay plaintiffs’ legal fees.) “Everyone knows the word ‘co-op’ is a synonym for ‘Jewish housing,’” the influential Puerto Rican Bronx political operator Herman Badillo said in 1988. “Puerto Ricans and Hispanics don’t understand co-ops and don’t have the money for co-ops, and neither do Blacks.” For all its crass racialization, Badillo’s comment registered a real concern: that New York cooperative housing had become a form of government subsidy, via low-interest loans, for the white middle class.

TODAY, the Coops are owned by a company called Galil Management LLC. According to Who Owns What, an organization that tracks the property portfolios of New York City landlords, there are almost 900 open violations on the two properties, with over 150 rent-stabilized units deregulated since 2007, and 24 evictions in the past year alone. Covid-19 ravaged the Allerton area; zip code 10467 currently has the second highest caseload of any in the city, and the fourth most deaths. Its residents are people of color who face crowded, unsafe housing and high rents, with some of the city’s highest rates of eviction and housing code violations.

Their situation, of course, is commonplace: Working-class tenants today face concentrations of wealth and power even more extreme, by some metrics, than those of the early 20th century. As the geographer and activist Samuel Stein writes in his book Capital City, “[t]here is not a single county in the country where a full-time minimum wage worker can afford the average two bedroom apartment.” According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there are only 145 counties (out of 3,141 nationwide) where that same worker can afford a one-bedroom. Deindustrialization has led to the rise of what Stein calls “the real estate state”: the power structure that emerges when rent, rather than industry, drives the economy in capital hubs like New York. In the real estate state, financial capital bloats the value of urban land, making it impossible to purchase property to build non-speculative housing when capital markets demand more profitable investments, like luxury apartments. The gap between wages and real estate prices is so extreme now that Depression-era levels of eviction and homelessness are normal even during boom years. Thousands of adults living in New York City homeless shelters work full time. Meanwhile, advocates of “affordable” housing—like the paternalistic reformers who sought to reshape the Lower East Side tenements—work in conjunction with developers who build a meager number of units in return for government subsidies and tax breaks, perpetuating a system that treats tenants as passive recipients of state welfare instead of the makers of their own homes and futures.

There is no shortage of cooperative energy in the Bronx of the past 50 years. In 1978, as the borough was set aflame by landlords seeking insurance payoffs, members of the Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association defended their blocks from fire, uniting under the slogan, “Don’t move, improve!” Today’s Green Worker Cooperatives are training workers to found ecologically sustainable cooperative businesses in the South Bronx. But with wages stagnant and real estate costs ballooning, the idea of workers building their own housing feels like a more remote dream than ever. In light of all this, it is both sobering and inspiring to remember simply what the Coopniks did: Seven hundred working households pooled all their savings from decades of making clothing in dangerous conditions—and still had only around one-sixth of what they needed to build a home for themselves. They were determined to build infrastructure at the scale of the state and yet to cooperate with the state and the market as little as possible; this did not escape notice, and the state and market closed in on them. The Coops could have saved themselves, and gradually negotiated away their commitment to their vision of housing as a base for radical opposition to capital. The majority didn’t want to.

Avi Garelick is a researcher and organizer based in Washington Heights, New York.

Andrew Schustek is a writer and researcher in New York City.