The Best Argument for Socialism

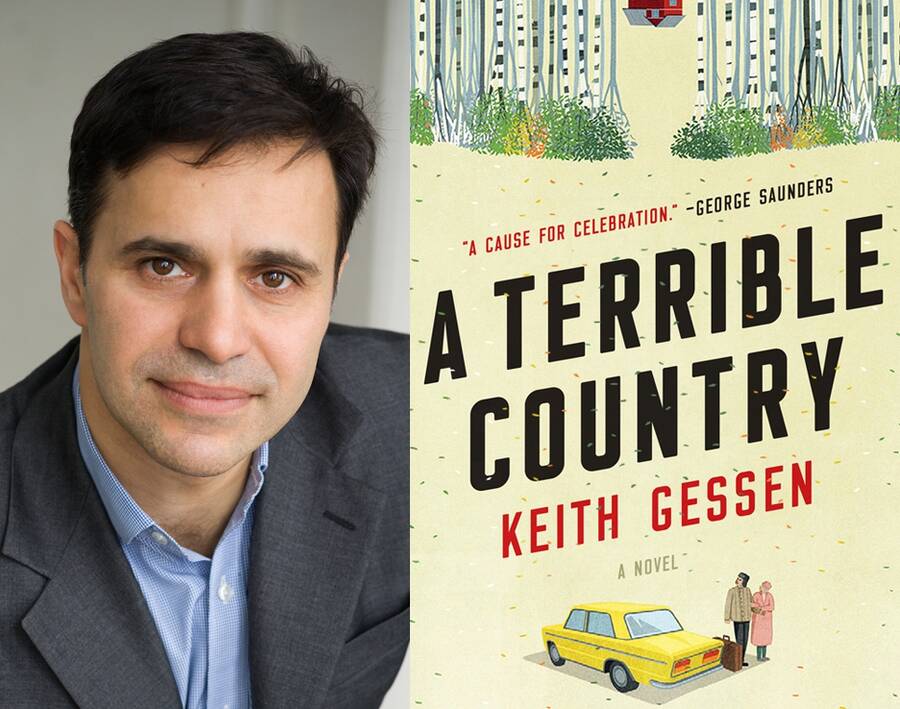

An interview with Keith Gessen about his new novel, A Terrible Country.

I met Keith Gessen in 2015 when he was a Fellow at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. He was researching his second novel, which was then simply called Russia. The book, now called A Terrible Country, follows Andrei Kaplan, a graduate student in New York, as he moves to Moscow to take care of his ailing grandmother and learns to navigate Putin’s Russia over the course of a year. The novel, which unfolds with unexpected humor, is about intimate relationships, familial and social, and the tests they are subjected to under different state regimes. It is also about the ease with which one can enter and leave certain ways of life, and who is free to make those choices.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Lauren Goldenberg: I keep coming back to the aspect of the novel that struck me most on a personal level—the grandmother. When I first wrote to you and told you how she made me think of my own, you said I was not the first person to tell you this. Was the grandmother always going to be central to the story? Did you intend to write a portrayal that was both intimate and universal?

Keith Gessen: The book was always going to be about a guy who goes to Moscow to take care of his grandmother. Everything else was negotiable. But the role of the grandmother changed over time. I was very wary of turning her into a magic grandmother, the bearer of some occult knowledge or secret. A friend who I show my work to kept half-seriously suggesting that she should have stashed away some secret manuscript, for example about the Holocaust, which Andrei would find and then bring to the attention of the world. The book would be called The Holocaust Diary. Guaranteed best-seller. And, don’t get me wrong, I was definitely tempted to do that! But it’s the sort of thing I’m not good at as a writer. And also, of course, it’s everything I hate about writing on Russia and Jews and history. So there were drafts where the grandmother kind of receded from view, or was only really there in the domestic sphere—you had Andrei’s home life and then his public or political life where he became a socialist (and his becoming a socialist was I guess the other non-negotiable aspect of the book) and these were basically separate or in tension. The breakthrough was when I realized that the grandmother and the socialism were actually part of the same story. It was a kind of gradual process of throwing out all the stuff that was boring or not part of the story: a long summary of Chapter 7 of Capital or a capsule biography of Marx.

LG: I, for one, am relieved there is no summary of Capital nor a mini-biography of Marx. How were those cuts made?

KG: I cut the long essays about Marx and so on when I read through the initial draft and found that it was totally unreadable, like by any human being, including me. Once that stuff got thrown out, it was much easier to see that actually the grandmother’s life was just about the best argument that anyone in the book could make for socialism. So then the grandmother became more central, which I think was a good thing.

I’ve been very surprised every time people tell me that it reminds them of their grandmother or grandfather or aging parent. I was definitely trying to describe a very specific grandmother. But I guess there is a kind of universal grandmother out there, with, you know, regional particularities.

LG: I think it’s interesting that you say her life is the best argument for socialism. I think through her you see the realities of that life—that some things were easier, but at such costs . . . Perhaps I’m showing my hand here a little—my father and his family didn’t leave Romania until 1970, and it’s very hard for me to shake a certain inherited reaction to the word socialism.

KG: I think for a lot of people from the older generation socialism means camps, shortages, propaganda, antisemitism, the whole bag. One of the interesting things to me, actually, watching the recent resurgence of socialism in the US, has been how few young people care about Russia and its socialist experience at all. Which is as it should be. The experience with socialism of a poor country in the 20th century is not that relevant to a rich country in the 21st century. But it’s natural for the young Russian socialists to think about it. For the older characters it does sometimes have multiple valences. Some of it is their youth and their idealism. Some of it they liked.

LG: It’s been an exciting few weeks on that front here in the US, certainly in New York, with Ocasio-Cortez’s win. Andrei becomes a socialist in Russia, though at the end of the novel, with his return to the US and his cushy academic job, it’s not clear how steadfast that position will remain . . .

KG: I think it’s a very interesting question, how people move to the left. In my case, it was my encounter with Russian capitalism. The ideological journey that Andrei goes through in the book is a journey that I took over the course of many more years. When I first came to Russia as a college student in the mid-90s, I thought like a good American that the Russians needed to carry out the reforms and destroy the communist heritage root and branch—that this was the great drama of those years, reformers versus communists. But eventually I realized that the reforms were being carried out and that they sucked! And that there were huge numbers of victims that everyone just wished would die off. And that the criminality and inequality that accompanied them were not some kind of aberration of capitalism, but capitalism as it actually exists in most places in the world. Once I realized that, I found myself holding a very different view of capitalism.

[The move left] is usually a personal experience, rather than an intellectual one, and then you need someone to explain how and why these things happened. Andrei, in the book, basically sees how his grandmother has been immiserated by the post-Soviet reforms, but it requires him meeting Sergei and the others for him to kind of put it together into a story that makes sense. So it’s very important for the left to continue to expand its media footprint, both its own media and its presence in larger, mainstream outlets, so that we can explain to people that their lives are being taken from them not by immigrants or the Chinese, but by capitalists, the expropriators of their labor, their environment, their life chances.

As for Andrei when he comes back, I think he becomes a leftist professor. He teaches his students about the ravages of the post-Soviet reforms. He hangs out on the fringes of Occupy. He joins DSA. I hope he has the courage to support the grad students and the adjuncts in their fight for union protections. But you never know until it happens.

LG: The portrayal of antisemitism felt very deftly done and true. In the novel, antisemitism and the fact of Andrei’s Jewishness are lurking in the background—until they aren’t. I was wondering if you could share a little more on this, both in the sense of writing this aspect into the novel but also how it relates to life in Russia at the time and now.

KG: Antisemitism is tricky. One of the best books I read while writing this one was Gal Beckerman’s When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone, which showed that the movement to “save” Soviet Jewry was based on a misunderstanding. Beckerman found these Jewish guys from, like, Cleveland who were the initiators of the movement to save the Soviet Jews in the 1950s, and it turns out that they all felt really bad about the Holocaust and how American Jewry didn’t do anything about it, and then when they started reading about the plight of Soviet Jews, they were like, Oh no, it’s another Holocaust, we have to stop it! And they started this mass movement which eventually led to the Jackson-Vanik Amendment, which tied US-Soviet trade relations to the Soviets’ willingness to release Jews. And it worked—that’s how the first wave of emigration, including my family’s in 1981, took place.

But there were some problems. One was, as it turned out, that the Israeli government had partly cooked up this information campaign so that they could tap the largest non-American group of Jews out there—Soviet Jews—and get them to make aliyah. And while the American Jews may have believed that there was another Holocaust on the way, there wasn’t. At least not after 1953. There were restrictions on Jews, and there was antisemitism in public life, but there weren’t pogroms and there certainly wasn’t a genocide. But once this movement got going, there was no stopping it. And of course the third problem was that most Jews who left the Soviet Union didn’t go to Israel—they went to the US. Beckerman describes a hilarious argument between the Israelis and the American Jews, with the Israelis saying, Hey, we got this whole thing in motion, you have to make the Soviet Jews come here, and the Americans saying, fuck you, we didn’t do all this work so we could then turn around and tell these people where they had to live! So the joke was on Israel. But it was also on the American Jews. There’s a really nice story in David Bezmozgis’s first collection, Natasha, about a Canadian doctor who was active in helping to free Soviet Jews having two immigrant families over for dinner and basically insisting that they compete to tell him the most horrible story about their lives in the USSR. I don’t remember anything quite like that, but this feeling like, “You poor Russian Jews, you were so oppressed, we are so happy we were able to get you out”—that was very much a part of our first few years in the US. And it was tricky, because I think my parents were genuinely very happy to have come here, and were grateful to the Jewish agencies. At the same time, they had no interest in organized Jewish religion, and also no one likes to be condescended to, especially when, you know, most of the people who came over at that time had multiple advanced degrees. It was a pretty sophisticated group.

Anyway, to bring this up to the present, there was a period after the Soviet collapse when Jews became very prominent in Russian political and economic life. A disproportionate number of the early oligarchs were Jewish. And one of the reasons given for this is that because Jews were in many cases cut off from the legitimate Soviet economy, they had become adept at working in the gray and black markets, and when the whole country became a gray and black market, they were well-positioned to take advantage. Though in some cases, too, these people were quite successful in the official Soviet system. And this was unfortunately one of the planks of the red-brown coalition [of communists and far-right nationalists] in the 1990s, even as, on a day-to-day level, Jews weren’t considered an undesirable minority. Under Putin that hasn’t changed—some of Putin’s cronies (e.g. the Rottenberg brothers) are Jewish, and Putin doesn’t seem to be antisemitic at all. But it is part of the nationalist discourse, and it does come up now and again.

One of the incidents that I sort of based an incident in the book on was where I got into an argument with some people on the street who had put out a racist memorial to a soccer fan, and they were like, “Why don’t you go back to where you’re from and not tell us what to do.” And I was like, “Where do you think I’m from?” And they were like, “Aren’t you from Israel?” It was a shock because I just didn’t actually think I had “Jew” written all over me. And it doesn’t usually come up. Until, as you say, it does.

LG: Going back to something you said at the top, that the idea of a secret Holocaust manuscript was everything you hate about writing on Russia and Jews and history—is it that you hate reading that kind of writing, or that writing that type of thing is unappealing to you?

KG: I’d say in general that memory politics have had a terrible effect on contemporary politics—they’re almost always deployed to justify a nationalist political narrative that excuses bad politics in the present. The Russian historian Alexei Miller has argued provocatively that the entry of the Eastern European countries into the EU has undermined the historical basis for European comity, which was based on memories of the Holocaust—a reminder of the perils of nationalism. The Eastern Europeans came in and started arguing that communism was just as bad as Nazism, and that actually nationalism is good and healthy. This has had all sorts of bad effects.

In the US until very recently, Holocaust memory was deployed as a way of justifying the actions of Israel and also to argue that Jews couldn’t possibly be oppressors because they had themselves been oppressed. Not always—there have been progressive invocations of the Holocaust, including quite recently in connection to the child kidnappings at the border—but overall that has been the function of the Holocaust in American Jewish politics. So I sure didn’t want to participate in that.

Obviously there can be different uses of history and memory. One of the things that interested me in the novel was the grandmother’s actual relationship to the communist past and the capitalist present. She hated communism. But she misses much of the life and culture of that time. And she has been very much abused by the new system—in a way it was actually a collaboration between communism, which expropriated people’s labor and handed it to the state, and post-Soviet crony capitalism, which handed the fruits of that labor to a few well-connected men, that is at fault. So what do you do with that? It’s more complicated than “things were bad” or “things were good.” Things were always pretty complex.

Lauren Goldenberg is deputy director at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. She is a member of the Jewish Currents Board of Directors and of the Jewish Currents Council, and her book reviews and author interviews have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books and Music & Literature.