A forest defender at rest.

All photos from the Atlanta forest by Sasha Tycko.Shmita Means Total Destroy

A manifesto from the threatened Atlanta forest

Since we wrote this piece last fall about our fight to defend the Atlanta forest, the planned site of a police training compound and a media production facility, the terrain of struggle has shifted significantly. In mid-December, the Atlanta and DeKalb County police departments and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation staged a massive joint operation, entering the woods our movement has been occupying for the last year and a half with bulldozers and excavators to clear huge swaths of forest and destroy communal kitchens, shelters, and other life-sustaining infrastructure. They gathered under tree houses and launched round after round of tear gas and pepper balls at tree-sitters until they had no choice but to come down. They sent attack dogs after people on the ground. They arrested six people and charged them all with domestic terrorism. About a week later, Ryan Millsap, the film executive who is seeking to overtake a public park within the woods, returned with hired workers to rip the pavement up from the bike path and parking lot and bulldoze the gazebo at the center of the park.

In the face of these escalations, the movement remained resilient: Over the following weeks, forest defenders began to rebuild and reoccupy the forest. But on the morning of January 18th, 12 shots were heard echoing through the forest in rapid succession. The Georgia State Patrol had murdered our dear comrade, 26-year-old Manuel “Tortuguita” Teran. (The police, who say they have no body camera footage of the incident, allege that they were being shot at; they also initially claimed that they were ambushed, though they eventually admitted that Tortuguita was shot dead in their hammock.) With Tortuguita’s body still warm, the police immediately continued their operation in the style of December’s raid: destroying more forest, besieging more tree-sitters, and arresting seven more protesters, once again charging them with domestic terrorism. On January 26th, Governor Brian Kemp declared a state of emergency in response to protests in downtown Atlanta, summoning as many as 1,000 National Guard troops to heighten the assault on the forest defenders.

As our struggle continues, we are shocked, heartbroken, and devastated by the loss of Tortuguita, which has been felt acutely throughout our community. Tortuguita was an Indigenous anarchist and abolitionist who had been occupying the forest since May 2022. They had come here from Tallahassee, Florida, where they were involved in several mutual aid projects, including Food Not Bombs, rebuilding hurricane victims’ homes, and defending homeless encampments. They were also deeply invested in international struggle, with a particular commitment to Palestinian liberation; they could often be seen around the campfire sporting a keffiyeh. Though we didn’t know them as a practicing Jew (whatever that means), in one conversation they told us about one of their grandfathers who had survived a Nazi concentration camp. Their ancestors’ struggle for liberation fueled their antifascist politics. Tortuguita was as devoted to having a good time as they were to revolution, and their laugh could often be heard resounding through the trees. The forest is quieter without them.

We dedicate this piece to Tortuguita. May their memory be a blessing, and may the flame that burned in them burn every last prison to the ground.

When you enter the land that I assign to you, the land shall observe a Sabbath of the Lord. Six years you may sow your field and six years you may prune your vineyard and gather in the yield. But in the seventh year the land shall have a Sabbath of complete rest, a Sabbath of the Lord: you shall not sow your field or prune your vineyard. You shall not reap the aftergrowth of your harvest or gather the grapes of your untrimmed vine; it shall be a year of complete rest for the land.

—Leviticus 25:2–5

I. If We Cannot Rest . . .

Let’s be honest: We tried, and failed, to observe the Shmita year. We, the Fayer Collective—an informal group of Jewish revolutionaries, artists, workers, students, criminals, and free lovers experimenting with transgressive theory, action, and ritual—attempted to abide by this period of mandatory rest for the land and those who work it by waging war on work’s logic: of extraction, exhaustion, and enclosure. But for every squat we cracked—climbing through windows, changing locks—another collective house was evicted. Every water main we opened the city soon shut off again, this time under lock and key. We fled to the Atlanta forest to breathe fresh air and forage for food; but there were the police, poised to level hundreds of acres of trees to build the largest police training center in the United States. The institutional left tried every respectable means of action—which is to say, appealing to elected officials—but to no avail. So we built houses in the trees and camped out on the land, both to defend it from destruction and to avoid wasting more of our lives making rent. But the cops repeatedly raided our camps, slashing tents, puncturing water jugs, stomping on groceries, and arresting whoever they could get their hands on. Meanwhile, we worked our hated jobs to buy what we couldn’t yet make or steal. We are fighting, but work is winning.

For some 2,500 years, Shmita has sought to combat its tyranny. Hebrew for “dropping” or “release,” Shmita acknowledges that the land is alive and, like all living things, needs Shabbat, while knowing that it, too, has its own calendar, its own rhythm. Its cyclical movement to the asymmetrical beat of seven disrupts linear time and its myth of progress. In the Shmita year, all can gather what grows, regardless of property rights; debts against fellow Jews are forgiven, and Jewish slaves are freed. As the cycles multiply, so too does the magnitude of liberation: On the Yovel—the “Jubilee” year that follows every seventh Shmita year—all debts are forgiven, all slaves freed, and all property claims abolished as God reclaims the land. Shmita actively refuses to place humans and our projects at the center of the world. To accept its demands is to renounce our pride and its violences, to rectify human error and malice not through a positive solution, but by asking, “For once, can we just not?” We are released into the wholeness of the circle—the experience of living on this earth orbiting a ball of gas circling an unfathomable Nothing.

The justifications for ignoring this radical command are as old as the Shmita itself: Because the God of the Torah introduced the concept in relation to Eretz Yisrael, many rabbis have agreed that the agricultural aspects of Shmita do not apply to Jews in the diaspora; many have also argued that the law is only fully binding once the majority of Jews live in Eretz Yisrael. Other loopholes justify neglecting the Shmita while claiming to observe it. The Modern Orthodox movement employs a strategy first implemented in 1888 by the Russian Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor called heter mechira (leniency of sale), which holds that parcels of land can be temporarily sold to non-Jews for the Shmita year until year’s end to allow the original Jewish owners to work and profit off the land.

We are fighting, but work is winning.

A barricade made of debris blocks vehicles from

entering the forest.

The remains of a tree house belonging to the forest defenders chopped down by police over the summer.

The nonprofit world has its own version of this nominal observance. Today, liberal organizations with billionaire funders publish articles and host workshops about rethinking the Shmita for our modern era, proposing tepid solutions that pose no real threat to capital. One organization recommends “raising money to buy wilderness or jungle land and let it grow wild,” “donating to nature preserves,” and “volunteering to help clean parks.” There are calls to buy local foods, to support more sustainable forms of agriculture, to take some extra time off work. These proposals assume a framework of regeneration, not abolition: We must let ourselves rest so that we can continue to work; we must let the land rest so that we can continue to exploit it. A Shmita that remains attached to growth as such, that leaves our relationship with the land and the market fundamentally unchallenged, is not “release” but reform—a pathetic stopgap to keep the engines of progress running, to delay the machine’s inevitable collapse.

II. . . . They Will Not Rest

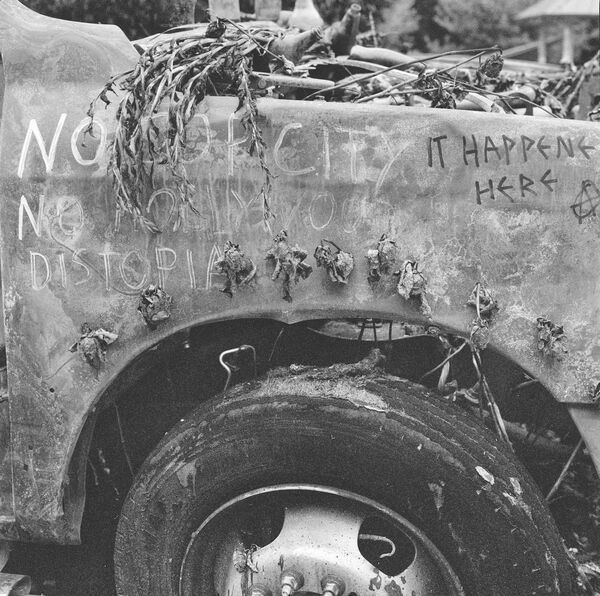

Surrounded by landfills, police firing ranges, cul-de-sacs of identical single-family homes, and a juvenile detention center, the Atlanta forest stands as a last bastion against the expansion of industrial society. But this nearly 400-acre wild space at the southeastern edge of the city is under attack. On the western side of Intrenchment Creek, a tributary of the heavily polluted South River, the Atlanta Police Foundation plans to build a $90 million dollar militarized police training compound, complete with a mock village for running SWAT drills and practicing crowd control tactics. On the eastern side, film tycoon and real estate mogul Ryan Millsap, who acquired part of Intrenchment Creek Park to construct soundstages, intends to raze the land. If completed, both projects—“Cop City” and “Hollywood Dystopia,” as they’re now commonly known—will increase catastrophic flooding in the surrounding neighborhoods and hasten ecological collapse, all while expanding the police state. These plans represent the latest chapter in a centuries-old saga of violence against the land and its inhabitants, beginning with the expulsion of the indigenous Muskogee people from the home they called Weelaunee. Settlers logged the land and made it a plantation; after abolition it became a prison farm, a site of legalized enslavement. Now flora and fauna conspire to reclaim it; kudzu and ivy creep over the prison ruins, smothering the walls and dissolving them brick by brick.

In perhaps the most urgent expression of our attempt to observe the Shmita, we’ve joined with others in the Defend the Atlanta Forest movement to help the forest seize its Sabbath. It started with a series of direct attacks on our enemies, from the Atlanta Police Foundation to the construction companies contracted for the projects. Earth-moving machines were sabotaged in the night and trees were spiked so they could not be felled. We began planting our bodies in the forest, occupation as obstruction. Our struggle against cops and capital is also a fight for spaces to actually experience the world, to truly see each other and ourselves. In a section of Intrenchment Creek Park we’ve named “the Living Room” we dance among the pines until sunrise, communing not only with one another but with all the forest’s creatures. Our music mixes with the deafening call of cicadas. An ambulance siren rushes by and a chorus of coyotes yips and howls their response. Frogs’ voices swell into post-technological trance songs. The wild symphony resounds over the surface of a nearby pond, where fish sleep and a smashed surveillance camera lies at rest, collecting algae.

The unconscious desire for Shmita bubbles up from below.

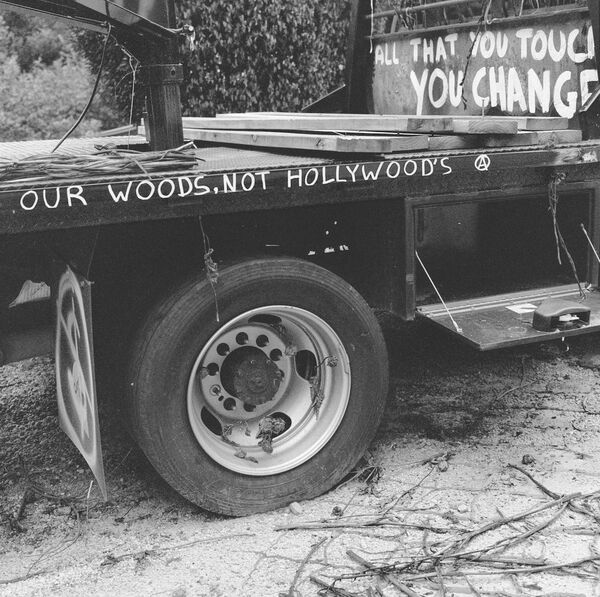

A truck owned by Ryan Millsap was destroyed after an attempt to tear down a gazebo in Intrenchment Creek Park while people were still inside. Since the summer, the truck has evolved into a work of public art, routinely adorned with political messaging.

In late July, the movement organized a three-day music festival to help Atlanta locals connect with the forest. To prepare, forest defenders removed cement barricades that Millsap had placed at the entrance of Intrenchment Creek Park—likely an illegal closure, since his alleged ownership of the land is tied up in court—and renamed the place “Weelaunee People’s Park.” On the morning before the third and final night of the festival, a worker and four off-duty cops arrived with a flatbed truck carrying an excavator, to tow our cars and destroy our gazebo. This new attempt to close the park was met with a hail of rocks and cans of seltzer, dispelling first the cops and then the worker who was operating the excavator, trying to demolish the gazebo with people still inside. “Buy your own forest!” he yelled back as he retreated aboard the excavator, red-faced and teary-eyed. The intruders left behind their truck, which was immediately scrawled with slogans and set ablaze.

That night we resumed the festivities, dancing with abandon to house and jungle, moshing furiously to hardcore and hip-hop. Everyone who joined us for that final night of the festival bore witness to the burned-out truck: an artifact of the morning’s creative destruction. Partygoers decorated it with lights and balloons, made it a backdrop for their selfies. In this image, the unconscious desire for Shmita bubbles up from below.

III. And the Land Will Seize Release

For millennia we’ve forsaken the Shmita, and now we owe a massive debt: a debt of rest, of unpruned vines, of unfreed slaves, of the destruction of debt itself. Leviticus makes clear that the abdication of this mandate will be met with violence. Informing the Israelites of the fate that will befall them if they break the covenant, God makes a ferocious promise: “And you I will scatter among the nations, and I will unsheathe the sword against you. Your land shall become a desolation and your cities a ruin. Then shall the land make up for its Sabbath years throughout the time that it is desolate and you are in the land of your enemies; then shall the land rest and make up for its Sabbath years” (Leviticus 26:33–34). The fields will lie fallow for one year every seven, or they will turn to dust and be swept away by wind and water. By flood or by fire, the land will take what it is owed.

By flood or by fire, the land will take what it is owed.

Here, at sword’s edge, our land desolate and our cities in ruins, the negative force of the Shmita is bulging out of its cage, overripe and ready to explode. It can no longer be contained within the rhythm of seven; it bloats and bursts forth into the potent now of messianic time. The Kabbalists say that this world was made through tzimtzum: the contraction of God’s infinite light, a divine act of negation to make creation possible. Today the voice of God speaks through the “crrreeeaaaaak . . . BOOM!” of an exploded gas tank. Shmita means attack; Shmita means total destroy.

A proposal for Shmita in the age of collapse: Quit your job. Cut holes in fences. Forgive everyone everything—except the agents of “progress,” who squeeze the world into a grid and don’t care who or what they crush. Befriend your neighbors: human, plant, and animal. Trade the mechanical time of clocks for the living time of the sun, the moon, the seasons. Sabotage all that sabotages your life. Block the roads. Destroy work, by flood or by fire. Steal everything that should be free, which is to say: everything. Don’t get caught. Learn what you desire and seize it, even if at first the pleasure frightens you. Breathe deeply, love frontally, attack anything that tries to deny you that power. Start now.

A previous version of this piece stated that Ryan Millsap currently owns the media production company Shadowbox Studios, formerly Blackhall Studios. In fact, Millsap sold the company in April 2021.

Fayer Collective is an informal group of Jewish revolutionaries, artists, workers, students, criminals, and free lovers experimenting with transgressive theory, action, and ritual in Atlanta.