Shaping the Neo-Hasidic Canon

A New Hasidism, a recent two-volume anthology, offers a compelling alternative to mainstream Jewish spirituality, but fails to fully confront the tradition’s consequences in the world.

Discussed in this essay: A New Hasidism: Roots, edited by Arthur Green and Ariel Evan Mayse. University of Nebraska Press, 2019. 432 pages.

A New Hasidism: Branches, edited by Arthur Green and Ariel Evan Mayse. University of Nebraska Press, 2019. 496 pages.

In response to this pervasive shallowness, a loose assemblage of non-Hasidic Jewish teachers and writers have, for the past century, tried to revitalize Jewish religious communities by turning to Hasidic Judaism, and working to make its ideas relevant and accessible to a changing world. This approach to Hasidic teachings, which originated in interwar Poland, has been described as “Neo-Hasidism” since the 1950s, when Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel popularized the presentation of Hasidic thought for diverse American audiences. A recent two-volume anthology—A New Hasidism: Roots and A New Hasidism: Branches, edited by rabbis and scholars Arthur Green and Ariel Evan Mayse—is the first attempt at a comprehensive presentation of Neo-Hasidism’s origins and development. Anyone in search of depth, rigor, and personal meaning in heterodox Jewish thought will find this anthology illuminating. As Green and Mayse write in their introduction to the first volume, Roots, “the insights of Hasidism are too important to be left to the Hasidim alone.”

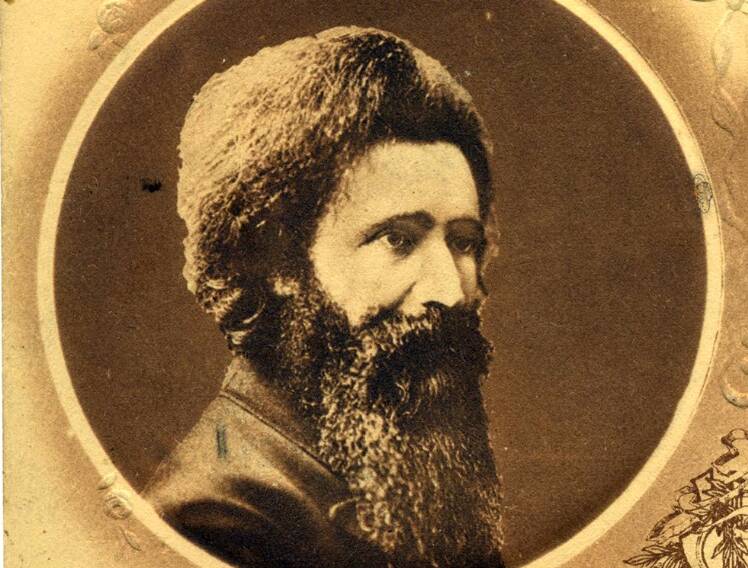

This might surprise progressive Jews accustomed to seeing Hasidism as a fundamentalist, socially conservative, and strictly hierarchical ideology. Today’s Hasidic communities are led by exclusively male religious authorities, and exclude women from communal leadership; the American Hasidic community supports Donald Trump by a two-to-one margin. Yet Hasidic Judaism was, at its inception, a radically democratic movement. Its founder, the charismatic 18th-century Ukrainian mystic Rabbi Israel Ben Eliezer—better known as the Ba’al Shem Tov—and his disciples hoped to leave behind the rabbinic elitism they saw as endemic to the Judaism of their time; they sought instead to create a populist culture of piety and devotion in which every Jew, regardless of their education, could access the deepest secrets of the mystical tradition, and find an immediate experience of God in even the most mundane moments of their lives.

Green and Mayse adopt this early Hasidic vision to guide their anthology. In an untitled manuscript from the mid-1920s published in Roots, the pre-Holocaust Polish writer and Neo-Hasidic thinker Hillel Zeitlin describes his goal as “bring[ing] into contemporary Jewish life the freshness, vitality, and joyful attachment to God, in accord with the style, concepts, mood, and meaning of the modern Jew, just as [the Ba’al Shem Tov] did in his time.” “Nearly a century later,” Green and Mayse write in a comment on this excerpt, “and in a world that neither Zeitlin nor the Ba’al Shem Tov could have quite imagined, the editors of the present volume[s] seek to do the same.”

The first volume, Roots, compiles teachings from six of the spiritual fathers of Neo-Hasidism: Zeitlin, Martin Buber, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Shlomo Carlebach, Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, and Green himself. The selections range from book excerpts and essays to interviews, speeches, and transcriptions of oral teachings. The second volume, Branches, surveys a broader terrain, collecting 18 essays by and interviews with contemporary Neo-Hasidic teachers—including psychotherapist Estelle Frankel, scholar and rabbi Shaul Magid, and Israeli rabbi and educator Elhanan Nir—each of whom addresses a particular aspect of Neo-Hasidic thought, practice, or community. Together, these essays and interviews present a diverse contemporary Jewish landscape, united by an insistence that, as Rabbi James Jacobson-Maisels writes in his essay “Neo-Hasidic Meditation” (2019), Jewish religious practices and teachings can “respond to our most pressing needs.”

What the thinkers gathered here offer most of all are innovative forms of textual exegesis. Hillel Zeitlin’s “Admonitions for Every True Member of Yavneh” (1924), one of the first selections in Roots, skillfully weaves together Jewish texts and secular thought, integrating questions of social justice and divine service in a way that might serve as a model for progressive Jewish activists seeking to plant their politics in a deep Jewish soil. These “admonitions” are Zeitlin’s rules for the Neo-Hasidic fellowship he hoped to establish in interwar Poland, and the first three—“Support yourself only from your own work,” “Keep away from luxuries,” and “Do not exploit anyone”—are as concerned with socialist ideals as with Jewish values. For Zeitlin, these two categories are intertwined: He condemns capitalism’s inequities as a matter of the utmost Jewish moral concern, in language that echoes tractate Sanhedrin of the Mishnah, the foundational Jewish legal code: “Every person has their own purpose. Every person is a complete world.” The original rabbinic discussion which Zeitlin references here concerns the sanctity of human life, and the destruction caused when a human life is unjustly taken. By linking this source with his “admonition” about economics, Zeitlin makes the subtle argument that capitalist exploitation is akin to murder.

In Branches, Rabbi David Sedenberg provides another model of Neo-Hasidic exegesis in his essay “Buiilding the Body of the Shekhinah” (2019), where he elucidates a wide variety of Kabbalistic and Hasidic texts to make the case for “recogniz[ing] the inherent holiness of the world around us as a dwelling place for the Divine,” thus establishing a rich and rigorous theological framework for Jewish environmentalism. And in “Neo-Hasidic Meditation,” Rabbi Jacobson-Maisels puts careful readings of Hasidic teachings in conversation with Buddhist thought to articulate a theory of Jewish meditation that might be meaningful for Jews who feel alienated from traditional forms of prayer, but are still eager for a rigorous Jewish contemplative practice.

For progressive Jews, what it might mean to connect with the divine is often unclear. My relationship to God, after all, is characterized by a deep and visceral ambivalence; I sometimes think of God as a kind of phantom limb, a presence I know only through the intimacy of its absence. Refreshingly, the thinkers compiled in A New Hasidism offer an expansive enough vision of Jewish faith for this kind of uncertainty and contradiction, while still imparting a framework for the direct experience of God’s presence in every moment of one’s life. “There is no set doctrine of God in the Neo-Hasidic view,” Green and Mayse write in their introduction to Branches, “and an insistence [that there is one] would immediately raise our antidogmatic hackles.”

But Green’s and Mayse’s reticence to be dogmatic raises questions: What boundaries, if any, separate Neo-Hasidism from other Jewish religious and cultural phenomena? And without clear boundaries, how can Neo-Hasidism be conceptualized—let alone representatively anthologized—at all? These questions would be less pressing if Neo-Hasidism were taught primarily through participation in active Jewish communities, as Hasidism is: In such a living system, Neo-Hasidism’s boundaries would be continually established and renegotiated through the dynamic processes of Jewish living. Rabbi Ebn Leader addresses this in his excellent essay in Branches, “Does New Hasidism Need Rebbes?” (2019), in which he insists that “if Neo-Hasidism is to be a living tradition, it must be transmitted through and in the context of the lives of the people who are living it.” He quotes Heschel’s teaching that “whoever tries to study Hasidism relying only on the written sources . . . is relying on artificial material and the living springs are hidden from his eyes.” If the truth of Neo-Hasidism resides not in study, but in a holistic way of life, then A New Hasidism is the “artificial material” Heschel criticized.

Green and Mayse are aware of this conflict between intellectual study and lived experience. In the introduction to Branches, they ask the reader “to search the essays for a gateway through which to walk,” and in the interview that closes Branches, Mayse states that he hopes “that the collection will be a gateway for others to forge a new path.” The repetition of “gateway,” which suggests transitional space, is telling: A New Hasidism is a means to an end, and that end takes place not in the study of texts, but in the activity of human life. Yet without a living Neo-Hasidic community or teacher to offer guidance, a reader might experience this anthology less as an open door than as a closed but illuminated window.

This predicament could have been avoided if A New Hasidism offered clear guidance on how to live a Neo-Hasidic life. But the anthology’s lack of specific practices or instruction, though occasionally frustrating, is also among its many virtues. A reluctance to be prescriptive increases the burden on the anthology’s readers, but it also feels like a gesture of respect: We are each, whatever our Jewish education or background, fully authorized to find and walk our own authentic Jewish spiritual paths. We rely on no rabbinic imprimatur, A New Hasidism suggests; we are the only Jewish authorities we need.

But this hands-off approach to Jewish instruction sometimes manifests as a shirking of responsibility. However capacious Neo-Hasidism might be, an anthology—which presents a selection of texts and thinkers that define a tradition—is necessarily a project of inclusion, exclusion. Green and Mayse understand this, but shy away from the task of really reckoning with the Neo-Hasidic lineage. They rightly include no work by the Chabad-affiliated Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh—one of Israel’s most influential teachers of Neo-Hasidic mysticism, who has explicitly condoned the murder of non-Jews, celebrating Baruch Goldstein’s 1994 massacre of 29 Palestinian worshippers in Hebron, and who understands his own violent fanaticism as inextricable from Neo-Hasidic thought. The anthology does feature two responses to Ginsburgh’s role in the community: Don Seeman’s “The Anxiety of Ethics” (2019) discusses the tendency of direct, mystical experience to trigger a dangerous fundamentalism, and calls for the re-centering of ethics in Neo-Hasidic discourse, and in the interview that closes Branches, Mayse says that “many of us struggle with the way the Hasidic sources are used to justify stances and actions we find morally abhorrent.” But taken together, these attempts to deal with the reactionary violence aligned with Neo-Hasidism fall short of a true interrogation.

Another, quite different case of exclusion shows the ways in which Mayse and Green fail to fully embrace the responsibility of anthologizing. Roots includes no contributions from women, and all but three of the 17 selections in Branches are by men: Two are written by women—Estelle Frankel and Rabbi Nancy Flam—and a third is an interview with the Israeli scholar and poet Haviva Pedaya. Green and Mayse, in their introduction to both volumes, acknowledge this imbalance, writing that they “wish [they] could have included . . . a greater representation of women’s voices.” But as in the case of Ginsburgh, a simple acknowledgment of the problem stands in for a real attempt to resolve it. After all, Green and Mayse are not passively inheriting a tradition; in anthologizing Neo-Hasidism, they are simultaneously creating it. And there is no dearth of important female Neo-Hasidic teachers and leaders: Rabbis Shefa Gold, Ruth Gan Kagan, and Mimi Feigelson are just a few of the influential thinkers who could have been included.

In her essay in Branches, “Training the Heart and Mind,” Flam describes the experience of this exclusion. “To read Hasidic texts,” she writes, “is to enter a gendered universe . . . created by and for men.” The human stakes of this “gendered universe” are not abstract: Since the late 1990s, many women have accused Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, whose teachings are anthologized in Roots, of sexual assault and harassment. It is now clear that Carlebach was a serial abuser of women and girls over several decades, and that his influence in the Neo-Hasidic world enabled his abuse while silencing his victims. The editors of A New Hasidism devote one paragraph of their 16 page-introduction to Carlebach’s life and work to his role as an abuser. “There is no disputing that Shlomo sometimes acted toward young women in his orb in . . . deplorable ways . . . [t]his should be stated without equivocation or defense,” they write. And yet for further reading they recommend as “excellent,” without qualification, a biography of Carlebach that alternately ignores and delegitimizes all the accusations against him, written by a man who as recently as 2019 has slandered Carlebach’s accusers on social media. The gendered universe Flam describes will persist until those who draw on the Hasidic tradition take seriously the task of undoing its patriarchal norms; Carlebach’s legacy demonstrates this task’s urgent necessity.

These lapses and abiding questions point to fundamental tensions within the project of A New Hasidism: Neo-Hasidism’s goal is to facilitate an experience of divinity in the world, and yet without progressive communities of Neo-Hasidic practice and transmission, that experience risks being cut off from a holistic way of life. This gulf between the tradition’s teachings and the world can give rise to a complacency; perhaps it’s this un-rootedness of theory from lived experience that stops the editors from confronting the human consequences of the tradition’s failings and omissions with the appropriate urgency.

Nevertheless, A New Hasidism offers a compelling alternative to the forms and institutions of mainstream progressive Jewish religious life. Against an American Judaism that is too often uncomfortable talking about God, and tends to proclaim “Jewish values” while in practice celebrating assimilation, materialism, and shallow nationalism, Green and Mayse’s anthology situates the divine as an essential focus for progressive Jewish life, while offering innovative and rigorous models of Jewish exegesis. Its non-dogmatic insistence on—as Heschel writes in “Dissent,” a previously unpublished essay printed in Roots, which was found undated among Heschel’s papers—“deep caring, concern, untrammeled radical thinking informed by rich learning, a degree of audacity and courage, and the power of the word,” constitutes an invitation. For Green and Mayse, this anthology’s final, necessary chapters can only take place in the lives of its readers, who will accept or reject or reinterpret A New Hasidism’s flaws and insights differently as they strive for their own Jewish authenticity, and struggle with the divine.

Daniel Kraft is a writer, translator, and educator living in Richmond, Virginia.