Roth Versus The Rabbis

“It was presumptuous of you, Rabbi Rackman, to speak of yourself to me as ‘a leader of his people.’ You are not my leader and I can only thank God for it.”

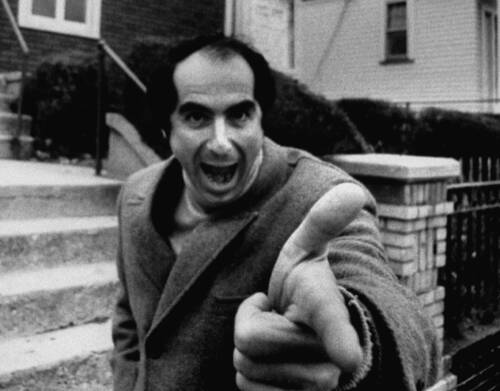

BEFORE PHILIP ROTH was celebrated, infamous, or dead, he was a very precocious kid writer. A story he wrote in college was chosen for The Best American Short Stories collection, and within a few years, his work was already being adapted for television by a world-famous director, Alfred Hitchcock.

He had talent, of course, but plenty of his earliest fiction was sentimental pap he’d never allow anyone to reprint. What’s most striking about that young Roth, and worth remembering as we mourn his death today, was just how clear-headed he was, already, on the issue of Jewish authority.

This tends to get a little confused in the way he’s remembered. The New York Times’ obituary, under a heading of “Irritating the Rabbis,” puts it this way: Roth was “denounced . . . by some influential rabbis,” so much so that in 1962, “he resolved never to write about Jews again” (but then changed his mind). The sense one gets—an impression Roth himself perpetuated, later in life—is that the writer was doing his own thing, minding his own business, when some silly rabbis showed up to pester him.

The truth is that Roth was gunning for those rabbis, and the attention that they devoted to him reflected only how successfully he had baited them. It was a fight he sought out, for a reason.

Roth did this most obviously, and overtly, with “The Conversion of the Jews,” the whole point of which was to portray an actual rabbi, forced to kneel and proclaim his belief in Jesus Christ. (Roth later described it as “the tale of a boy able to bring his overlords to their knees.”) But that had been published in a literary magazine, The Paris Review, and it wasn’t so easy to get your hands on. The attack that really landed was “Defender of the Faith,” which ran in The New Yorker on March 14th, 1959.

That story concerns a group of Jewish soldiers on a base in Missouri during World War II, and one in particular who preys on the sentimentality and yearning for Jewish community of his commanding officer to get special privileges. The portrait of this schemer, Grossbart, and of his slimy friend Fishbein, got under readers’ skins. A Zionist activist and old friend of Vladimir Jabotinsky, Eliahu Ben-Horin, got straight to the point and called it “an ugly piece of anti-Semitic literature.” One reader wrote, “I hated you personally every sentence of your story.” But the letters Roth cared about most were the ones from Rabbi Emmanuel Rackman, of Congregation Shaaray Tefila in Far Rockaway. Rackman was no joke—an Orthodox congregational rabbi and scholar with both a law degree and a PhD, who would go on to be appointed provost of Yeshiva University and eventually president of Bar-Ilan University.

Rackman was upset by the story, and assumed that he could do something about it. He wrote first to the Anti-Defamation League: “What is being done to silence this man? Medieval Jews would have known what to do with him.” Note the passive voice, and the assumption that in America, it might be possible to impose a cherem, excommunication, on a Jew like Roth, the way the Amsterdam Jewish community had been able to do to Spinoza. Of course, as Roth knew, in America, rabbis don’t have that kind of power; Rackman admitted as much, writing to Roth a few weeks later that “Jews like myself . . . have neither the economic, political, nor social power to do anything other than scream.”

To be clear, Rackman didn’t think that Roth shouldn’t write stories like “Defender of the Faith”; what concerned him was the question of publication, the ethics of criticizing Jews for a general audience. He explained to Roth that “the service you can render our heritage is to criticize its adherents in such a forum as will not hurt Judaism as well as Jews.” In a later letter, he clarified this point further: “Your story—in Hebrew—in an Israeli magazine or newspaper—would have been judged exclusively from a literary point of view. Publishing it, as you did, where you did, created the ethical question.”

Roth absolutely, and rightly, rejected the idea that Rackman could tell him what to do; he ended his very first reply like this: “It was presumptuous of you, Rabbi Rackman, to speak of yourself to me as ‘a leader of his people.’ You are not my leader and I can only thank God for it.” But Roth went considerably further than that. Four years later, in Commentary, Roth returned to the rabbi:

The competition that Rabbi Rackman imagines himself to be engaged in hasn’t to do with who will presume to lead the Jews; it is really a matter of who, in addressing them, is going to take them more seriously—strange as that may sound—with who is going to see them as something more than part of the mob in a crowded theater, more than helpless and threatened and in need of reassurances that they are as “balanced” as anyone else. The question really is, who is going to address men and women like men and women, and who like children. If there are Jews who have begun to find the stories the novelists tell more provocative and pertinent than the sermons of some of the rabbis, perhaps it is because there are regions of feeling and consciousness in them which cannot be reached by the oratory of self-congratulation and self-pity.

As much as, at first here, Roth suggests that it’s just Rackman who “imagines” himself in a competition with novelists, by the end of this passage, it’s clear that Roth knows he’s competing, too. He presents himself as, and certainly turned out to be, the novelist who would “take [Jews] more seriously.”

In the very first letter he wrote to Rackman—sent before Roth had published a book, before he had won the National Book Award, just a month after his 26th birthday, and to this day unpublished—Roth understood Rackman’s response to “Defender of the Faith” as Jewish McCarthyism, an attempt to silence criticism and demand “a kind of Jewish patriotism.” Even more striking than that was how, in that letter, Roth described his purpose in writing the story. It’s “not an anti-semitic story,” Roth explained to the rabbi, but “a story that calls for a responsible semitism, for a community united by love and mercy and kindness, and not manipulation and deceit.”

Roth’s legacy as a writer isn’t simple: his misogyny is real; some of his comedy won’t age well; and there are clunkers as well as masterpieces in his oeuvre. But thinking about what Roth has to offer us today, just a few weeks after the state of South Carolina passed a bill that gives legislators control over what you can and can’t say about Jews, it’s worth keeping his early self-assurance in mind. Sixty years ago, as an unknown twenty-something, Roth had already decided that he had as much right—and responsibility—to talk about Jews as anyone else, and certainly more than any self-important rabbis or self-proclaimed spokespeople. It goes without saying whose ideas about Jews have ended up, all these years later, traveling further and influencing more people. And as we think about who gets to speak and who gets silenced in conversations about Jews in America today, we could do a lot worse than to look to Roth’s work for a model of what “responsible semitism” can look like, in practice.

Josh Lambert is the Sophia Moses Robison Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and English, and Director of the Jewish Studies Program, at Wellesley College.