Remaking the Canon in Our Image

This emerging canon of American Jewish poets imagines Jewishness anew in its true complexity and multiplicity.

Discussed in this essay:

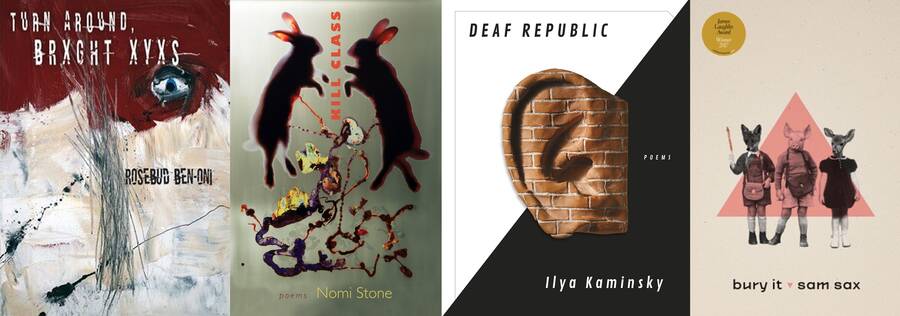

bury it, by sam sax. Wesleyan University Press, 2018. 88 pages.

Deaf Republic, by Ilya Kaminsky. Graywolf Press, 2019. 80 pages.

Kill Class, by Nomi Stone. Tupelo Press, 2019. 87 pages.

turn around, BRXGHT XYXS, by Rosebud Ben-Oni. Get Fresh, 2019. 64 pages.

WITH THE RISE in brazen antisemitism in the US (and around the world) I have lately focused my poetry on my Jewishness more intensely than ever before. The more threatened I’ve felt as a Jew, the more I’ve felt compelled to write into my Jewishness, and the more I’ve turned to other Jewish American poets for companionship and guidance. In this emerging canon of Jewish American poets, Jewishness is imagined anew in its true complexity and multiplicity.

Take, for instance, sam sax’s remarkable second collection, bury it. sax began his career as a slam poet, traveling across the country to perform, and the energy of this on-the-go orality—evocative of an itinerant diasporism—is inscribed into his poems, even as they sit still on the page. Unlike many Jewish poets of the last century—like Maxine Kumin or Gerald Stern—sax doesn’t offer slice-of-life vignettes or meditations on identity. Rather, continuing in the tradition of poets like Allen Ginsberg, sax writes nearly everything into his poems, trusting the connections to occur by means of his subtle shaping and control of every word, line, and line break.

bury it is concerned with the problems of surviving as a queer Jewish man in contemporary America. “& just like that the first boy i ever kissed is dead,” sax writes in a long poem called “Kaddish.” As Ginsberg does in his epic poem of the same title—“Blessed be He in homosexuality! Blessed be He in Paranoia! Blessed be He in the city! Blessed be He in the Book!”—sax links queer vulnerability to Jewish ritual practice, escalating the urgency of both. sax’s “Kaddish” ends: “i wonder / what they found / when they cut him / open / wings i bet / i bet they found wings.”

sax poeticizes the relentless assault of facts and matter in contemporary life, turning pain into something beautiful, without ever losing the starkness of that pain. These poems inhabit bodies at risk, which comes to feel like rebellion. In “Hydrophobia,” sax writes:

in the beginning there was a bath

& everything living thrashed

toward the surface

the ring around the tub

a mouth that only knows

to swallow

once I was young & holding

onto a man for dear life

take my cock bitch

& it was as if i were listening

through water . . .

This is the poet’s own Genesis, the recurring creation of a queer Jewish body aware of its own complex otherness, and its burgeoning resilience.

Like sax, Ilya Kaminsky—in his groundbreaking second book, Deaf Republic—asks: How will we exist across difference in this still-young century? Kaminsky, who emigrated from the Soviet Union as a teenager, filters the form of Eastern European parables through the lens of the horrors of the 20th and 21st centuries. The collection tells the tale of an imagined town suffering under a military occupation, whose residents choose to enact deafness as a rebellion against their occupiers (“Our hearing doesn’t weaken, but something silent in us strengthens”), using sign language as the medium of their dissent. But the selective deafness and ensuing silence is also used to illustrate a kind of neglect or complicity in their interactions with one another: In “The Trial,” Kaminsky writes:

Despite the darkness, Deaf Republic is rich with tenderness. It is also a love story. In Kaminsky’s work, as in sax’s, writing love and desire out of a marginalized identity is itself an act of resistance. Openheartedness is a risky mode, and Kaminsky pulls it off: “You are two fingers more beautiful than any other woman— / I am not a poet, Sonya, / I want to live in your hair,” he writes in “Of Weddings before the War.” The love here is storybook, if “storybook” means the kind of tale you tell your children to warn them that they will never be accepted in their homeland—and to spur them to fight for their own survival.

From the sidewalks, neighbors watch two women step in front of Galya.My sister was arrested because of your revolution, one spits in her face. Another takes her by the hair, I will open your skull and scramble your eggs! They grab Anushka, then drag Galya behind the bakery [...]

She shouts.

They point to their ears.

Gracefully, our people shut their windows.

Nomi Stone’s captivating second collection, Kill Class, also takes on questions of survival and complicity. The book demonstrates, chillingly, how the US has deployed cultural understanding to enhance its destructive capability. Stone, an anthropologist as well as a poet, uses her training to delve into communities not her own. (Stone’s first book, Stranger’s Notebook, emerged from time Stone spent with the Djerba, one of North Africa’s last Jewish communities.) The poems in Kill Class are set in Pineland, a country fabricated by the US military in North Carolina, in which people of Middle Eastern backgrounds are employed as actors to train military personnel in “local” customs and attitudes before they are sent overseas. The book reflects Stone’s work embedded in Pineland and other similar sites across the country.

In the title poem, Stone describes one such theatrical scenario:

. . . our child—there was a child—they made me eat his ashes.

I am supposed to arrive at the guerrilla camp full

of fury, and if possible, to cry.Commander: Do you take hot sauce on those ashes?

Stone, a rabbi’s daughter, once explained in an interview that growing up in a religious Jewish family attuned her to “questions of ritual and the aesthetics of ritual.” While the poems in Kill Class don’t engage Judaism directly, this interest in ritual is frequently made manifest in its pages. The habitualized artifice of Pineland becomes tangled with the real:

On the other side of the forest, men

scoop imagined ashes into a silver bowl.

A scenario hatched by the American military:

the Muslim village burns the Christian village.

Over the mock grave

they open the real earth

and plant fresh pinecones.

The actors who speak in Stone’s poems often feel suspended between worlds—othered and othering—balancing everyday American life with the job of pretending to be the enemy of the same nation or, more complexly, of trying to understand a people in order to destroy them. In “Mosque / School Room,” Stone writes, “Their Commander reminds them / to use rapport to get to the main point. Drink tea with them for an hour / at the very end, maybe you will get what you need.”

This suspension between worlds also features in Rosebud Ben-Oni’s phenomenal second collection, turn around, BRXGHT XYXS. Ben-Oni’s writing embraces Jewishness as it intersects with her Mexican and queer identities, resisting persistent limitations on mainstream Jewish narratives. Her poems reflect a diasporic kaleidoscope; they travel to Manhattan, Israel, Hong Kong, the Texas border, the Kentucky Derby, the moon.

Like the other books discussed here, turn around, BRXGHT XYXS wrestles with difficult subjects, including gun violence and abusive relationships. The propulsion and scope of Ben-Oni’s poems—engaging everything from biblical figures to ’80s music—give each word an exhilarating amount of power. In “All the Wild Beasts I Have Been,” Ben-Oni shines in her ability to write what feels like an ever-reverberating amount of meaning into each line, here illustrating the complexities of assimilation and interfaith marriage:

I burned the fields

I burned the wildflowers suddenly

I prayed for forgiveness

Kicked the door in

All the doors in Jerusalem

Now uncles now aunts now cousins

Calling on my wedding day

Why they ask can’t I understand

They will not under any law

Any sun

Any surfacing

Sanction my marriage

Ben-Oni, like sax, Kaminsky, and Stone, reimagines a Jewish canon as she writes it. In “If Cain the Younger Sister,” she begins, “My brother is a whitewashed synagogue . . .” and later continues:

He promised I was a complete

Mensch and mother’s family too

Ofrenda of flower, skull and bread.

At ten he solved a dispute

By reciting Kaddish

On the Day of the Dead.

My brother would bury me if he had to.

turn around, BRXGHT XYXS audaciously owns its otherness, traveling the world—and the universe—without losing sight of the United States we now inhabit.

Living and writing as an American Jew in the 21st century often feels frightening and isolating. But being in these poets’ company make it less so. As we together reshape the canon of Jewish poetry, we have the opportunity to remake it in the image of a wider Jewish community than has ever before been represented. In so doing, we can bring out not only new understandings of our community’s struggles, but also insight and beauty beyond anything we’ve ever known.

Lynn Melnick is the author of the poetry collections Landscape with Sex and Violence and If I Should Say I Have Hope. Her poetry has appeared in The American Poetry Review, The New Republic, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Poetry, and A Public Space.