Portraits of Empire

George W. Bush’s recent book of paintings betrays liberal empire’s role not as fascism’s alternative but as its co-conspirator.

This review appears in our Fall 2021 issue. Subscribe now to receive a copy in your mailbox.

Discussed in this essay: Out of Many, One: Portraits of America’s Immigrants, by George W. Bush. Crown, 2021. 208 pages.

NOVEMBER 7th, 2020, was a day of public exuberance in the United States. Friends and family across the country exchanged videos of far-flung celebrations: firecrackers exploding, music blasting from balconies, cars emitting jubilant honks. Whatever you thought about Joe Biden, at least Donald Trump was out. It felt like new futures. Nevertheless, the old ways persisted. Enjoying these celebrations required thinking about Biden as not-Trump, rather than as architect of the racist 1994 crime bill that expedited mass incarceration, who, months into a global uprising against the brutality that is policing, suggested that instead of aiming to kill targeted people, cops should “shoot them in the leg”—a pithy expression of liberalism. The warped lens through which Biden’s presidency appears as anything other than an extension of the ongoing catastrophe of US empire is the result of a long history of nationalist distortion, in which carcerality masquerades as care, civility as justice.

Over the course of Donald Trump’s presidency, we saw an instance of such distortion unfold in real time, in the glow up enjoyed by former president and imperial warmonger George W. Bush—a revision that helped lay the groundwork for misunderstanding Biden as a radical departure from his predecessor. While Bush’s repressive policies continued to find new expression, he metamorphosed in the popular imagination, appearing in headlines not as the founder of ICE but as the recipient of a warm hug from Michelle Obama at the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, an affable friend of Ellen DeGeneres, and an amateur painter. The rehabilitation of Bush’s image was, of course, facilitated by Trump himself, whom Bush all but named when he declared in 2017 that “we’ve seen our discourse degraded by casual cruelty.” It’s easy to see how Trump’s unabashed malice cast Bush’s genteel bumbling as comparatively benign. But a closer look exposes a regime of perception that enables escalating repressions by casting mutual reinforcements as oppositional. By affirming Trumpian, self-avowedly delighted violence as the frontier of the unacceptable, complementary revisions to Bush’s legacy have expanded the scope of acceptable atrocity.

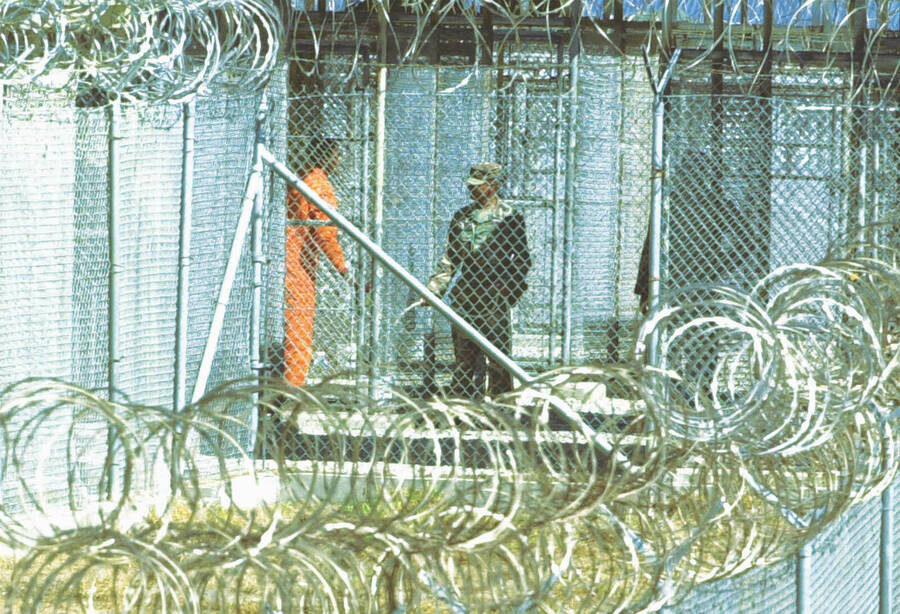

Bush’s paintings have played a peculiar role in this revision, attempting to shore up a sense of the former president’s beneficence, an aspirational erasure of his extraordinary harm. Could a violent man recognize the humanity in the face of another?, his portraits seem to say, weakly asserting a visual legacy to override the most indelible visual texts of Bush’s career: the images of detainee torture at Guantánamo. Now, four years after the release of his first book of paintings, Portraits of Courage: A Commander in Chief’s Tribute to America’s Warriors, a selection of new works is featured in another coffee table book, Out of Many, One: Portraits of America’s Immigrants. In one sense, this volume doesn’t matter; if these unremarkable paintings were not the work of a former president, they would never have made it off the family estate. But in another, the book is a curiously revealing document—an artifact that betrays liberal empire’s role not as fascism’s alternative but as its co-conspirator.

The book is a curiously revealing document—an artifact that betrays liberal empire’s role not as fascism’s alternative but as its co-conspirator.

THE COVER OF OUT OF MANY, ONE features a grid of portraits (including one I initially mistook for a self-portrait but turned out to be a painting of Salim Asrawi, who fled the civil war in Lebanon and founded a steakhouse in Texas). When I first encountered the multiracial patchwork, it felt vintage—a relic of the 1990s-era mandate to depict visible differences that metonymize static identities. This visual economy of multiculturalism might be traced to the 1971 commercial in which an interracial group of beautiful people stood atop a hill singing, “I’d like to buy the world a Coke,” a rebuke to the costliness of segregated advertising in a nation reordered by the civil rights movement. Like any other reform designed not to contend with the conditions that made it necessary, corporate multiculturalism failed to bring about meaningful transformation, substituting the optics of difference for structural reckoning. I opened the book prepared to find Bush’s portraits likewise selling me the myth of the United States as a beacon of liberty for all.

When I turned to the images, I was taken aback. The cover had primed me to expect unknown-to-me subjects made intelligible by Bush’s brush as collective evidence of an inclusive nation, but I knew several of these people already: Madeleine Albright, Henry Kissinger, Arnold Schwarzenegger. What had at first felt retro now felt au courant. These familiar figures—immigrants who have themselves become architects of American empire—emblematize how the representational logic of multiculturalism has now been thoroughly integrated into late capitalism’s brutal coercions, democratizing the promise: “You, too, can harm people who look like you.” Today, a “girlboss” is a thing that makes cultural sense, and the CIA produces recruitment videos featuring diverse operatives who quote Zora Neale Hurston and spout garbled distortions like, “I am a woman of color. I am a mom. I am a cisgender millennial who’s been diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder. I am intersectional.”

While the cover’s political charge seemed neutralized by the quaint impotence of its vintage aesthetic, the portraits inside felt actively engaged in a struggle over the meanings of histories. Representation, of course, is an apt site for contesting configurations of power. To represent means to respond to someone’s needs and desires, as well as to extract their image so it exists independently of them, and liberal empire exploits this conflation. As scholar Kandice Chuh writes: “Within the logic of modern U.S. politics . . . national identity / subjectivity is offered as a substitute for justice.” In Western art, the portrait has traditionally served as a visual claim to subjectivity. Bush’s use of the classical style of portraiture, which confers dignity onto its subjects by allowing them to confront the viewer face-to-face, functions as a horrifically frontal and painfully inadequate counterpoint to the infamous image of a detainee receiving electric shocks with a sack over his head.

Out of Many, One features 43 portraits of immigrants from 35 countries. Aesthetically, the paintings are relatively uniform. Rendered mainly in pastel colors and with loose brushstrokes, they nod toward Expressionism—though, as scholar and critic Zoé Samudzi suggests in Art in America, their style is perhaps better understood as aspiring to realism. Some, like the portraits of “Dreamer” Carlos Mendez and Microsoft director of business development Tina Tran, appear muddled; others, like the depictions of Bush look-alike Salim Asrawi and asylee Sumera Haque, feature more distinct lines, as if the artist is haphazardly experimenting with technique. But to look too closely at the paintings themselves would be to grant too much to the book’s own framing—to indulge in liberal empire’s own self-mystifications, and in the delusion of Bush as guardian of immigrants’ images and their stories. As Samudzi points out, “The book is not actually about immigrants, it is a part of a vanity project.” The vanity of this project exceeds the egotism of believing that mediocre paintings deserve a national audience; it is reinforced formally. Each portrait is accompanied by a brief biography of its subject as narrated, with a bizarre degree of self-referentiality, by Bush. Paula Rendon, who immigrated from Mexico and worked as a nanny and housekeeper for the Bush family for six decades, “was like a second mother to my siblings and me.” Kim Mitchell, originally from Vietnam, is a graduate of the Bush Institute’s Veteran Leadership Program, a post-9/11 project committed to “supporting and enabling our nation’s warriors in their new missions as civilians.” “We counted every minute until Operation Iraqi Freedom started,” relays an immigrant from Iraq, formerly known as Ali. Upon becoming a US citizen, he changed his name to Tony George Bush.

The subjects depicted here are united, Bush tells us in the introduction, by “their resilience and perseverance, their patriotism, their generosity, and perhaps most of all, their gratitude. To a person, they expressed profound thanks for being here and determination to make the most of every opportunity.” The triumphalist narratives are formulaic. “I did not know what to do with my life in the US and was totally overwhelmed by the grand freedom that I suddenly had,” says Joseph Kim, an immigrant from Hoeryŏng, North Korea, who found occasional work in a coal mine after his father died in the famine and his mother in a labor camp. Now, he is “a cheerful, friendly, funny, and talented member” of the Bush Institute, where he is an “expert in residence” at the Human Freedom Initiative. Javaid Anwar grew up in Pakistan in the 1950s. “I was never respected in my own country,” Anwar, now an oil executive, explains. “[America] changed my life. It gave me chances I can never repay.”

This is “a story in which we are invited to know the refugee’s sorrow, and her indebtedness for its cure in order to tell us something meaningful about the genealogies of liberal power that undergird the twinned concerns of this scene: the gift of freedom and the debt that follows,” scholar Mimi Thi Nguyen writes in The Gift of Freedom. Nguyen is writing about Madalenna Lai, a Vietnamese refugee who purchased a float for the Rose Parade so she could thank the US in front of a worldwide television audience of 350 million people. Lai’s story is not featured in Bush’s book, but it doesn’t matter; the grammar of gratitude is fixed. Nguyen lays out how “freedom is precisely the idiom through which liberal empire acts as an arbiter for all humanity.” Freedom, she shows, is always “produced” by the imperial center in the context of an enduring global “deficit,” which authorizes its export by any means necessary.

Bush knows something about how the gift of freedom works. “[W]hile the price of freedom and security is high, it is never too high. Whatever it costs to defend our country, we will pay,” he said in his first State of the Union address, just months after 9/11, concluding the sentence where he called for “the largest increase in defense spending in two decades.” The next year, Bush made promises to Iraqi civilians: “We will tear down the apparatus of terror. And we will help you to build a new Iraq that is prosperous and free . . . The day of your liberation is near.” It was how he announced the US invasion.

“Every empire . . . tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires, that its mission is not to plunder and control but to educate and liberate,” Edward Said wrote in a 2003 article in The Los Angeles Times. When patterns of immigration are contoured by imperial violence, a book for immigration but not against imperialism is a book for imperialism with better branding. This nationalist PR campaign (a world tour!) hinges on the fact that immigrant is not in itself a meaningful subject position. The strategic use of its radical incoherence is laid bare by the formal equivalence of, for example, Thear Suzuki, who came to Texas with her family in 1981, fleeing the Khmer Rouge, and Henry Kissinger, the former US national security advisor and secretary of state, who at least passively facilitated and perhaps actively participated in the genocidal regime’s infamous massacres. The American Dream means that one refugee can make another.

The American Dream means that one refugee can make another.

Indeed, the knotty harm is foundational. Out of Many, One opens: “On a stormy Atlantic crossing in 1630, one of the first immigrants to the New World wasn’t sure he would make it. The Puritan John Winthrop knew that America was worth the risk, writing that it would be ‘a city upon a hill,’ a place of refuge and liberty.” Invoking a settler colonist who kept three Pequot people enslaved is the closest Bush gets to naming the nexus of immigration and violence responsible for the nation he so reveres. To address the founding colonists’ campaigns of genocide against Indigenous peoples or participation in the transatlantic slave trade would not only undermine Bush’s assertion of America’s “noble intentions”—voiding the nation’s claim to produce freedom—but would also explode the project’s more specific premise: that precisely because the US is a “nation of immigrants,” its form is ultimately unassailable. The book requires those erasures in order to cast liberal empire as benign; liberal empire requires those erasures to underwrite the enduring afterlives of those original violences, which are its lifeblood.

Like the book’s final, two-page section, “Why We Need Immigration (And Reform),” which emphasizes the twinned principles of “robust” immigration and “secure” borders, the portraits themselves ultimately amount to a case for the kind of reform liberal empires require in order to expand. Presenting images of diverse immigrants, united only by their gratitude to the United States, Out of Many, One creates a composite sketch of a “good immigrant” to authorize the very imperial aggressions which, by creating conditions of global unsafety, coerce people to leave their homes. Under the guise of hospitality, the book patrols the always unevenly porous border of the nation that has little relationship to its geographic perimeter—where dominant ideas of what “good” and “bad” look like are reproduced, where routes of appeal are fortified, and the addressee is always the imperial center. “But it wasn’t inclusion that I wanted,” the poet Dionne Brand writes of colonial narratives in An Autobiography of the Autobiography of Reading. “I wanted to be addressed.” When a project appeals to empire, as Bush’s does, power makes the meanings. The rest is just adornment.

Claire Schwartz is the author of the poetry collection Civil Service (Graywolf Press, 2022) and the culture editor of Jewish Currents.