Portrait of a Siege

Jehad al-Saftawi’s photographs in My Gaza make up an intimate archive of daily life amid destruction.

Jehad al-Saftawi has spent years photographing the gruesome human toll of the war in Gaza, but some of the most searing images gathered in his new book are everyday encounters that the photographer captured in his wanderings through the city. One image in My Gaza: A City in Photographs shows a boy in a classroom smiling into the camera while his classmates laugh at their desks in the background. The peaceful scene is marred by the long scar stretching across the child’s face, the trace of an Israeli bomb attack that killed 48 members of his family in 2008. In another, a young boy bikes past the bright blue front door of someone’s house, which still stands on its hinges even though the building it once opened into has been reduced to rubble. Al-Saftawi’s photographs, like the landscape of the city, are indelibly marked by brutality, even when the violence remains out of the frame.

Al-Saftawi, 29, began photographing life in Gaza while growing up in the neighborhoods now documented in his images, during a time of violent political upheaval. In 2005, Israel disbanded its settlements in Gaza; soon after, the militant fundamentalist party Hamas won control of the strip. Israel responded by intensifying its blockade of Gaza, depriving inhabitants of basic necessities; it also began invading the narrow strip of land with increasing force and frequency. In 2008, al-Saftawi captured the aftermath of two devastating Israeli attacks in his photographs, and he soon began working as a freelance documentary photographer. His work garnered international notice in 2014, when photos he took during Operation Protective Edge circulated widely in outlets like Reuters and Al Jazeera. That summer, he also livestreamed scenes of the war from his apartment; hundreds of thousands of people watched as Israeli missiles rained down on the city in a terrifying display of fireworks.

Al Saftawi’s career choices and political commitments are unorthodox considering his family’s prominent role in the politics of the region. His grandfather was Asaad al-Saftawi, a leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, a friend of Yasser Arafat, and a co-founder of Fatah, the ruling political party of the Palestinian Authority, who once hosted Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in his home in Gaza while they negotiated a peace agreement. His father, Imad al-Saftawi, pursued more militant strategies for Palestinian liberation, and spent 18 years in jail in Israel before returning to Gaza City in 2018 to work for Hamas. Jehad, one of five children, had already applied for asylum in the United States by then, and now lives near San Francisco with his wife, Lara, also a Palestinian journalist and photographer.

My Gaza collects images and stories of everyday people and the lives they lead in the middle of a city often described as a prison or a warzone. Al-Saftawi’s photographs orient us within the daily routines of the city; his camera remains primarily focused on the streets of Gaza and the people gathered there. But the rare photographs of his domestic life included in the book afford glimpses into his family home, where he and Lara negotiate their fraught relationship with his father’s legacy and the atmosphere of religious conservatism that has flourished under the Hamas regime.

In this conversation, al-Saftawi shared some of the personal stories behind his photographs, and talked about how his photojournalism led him to question his political education. Throughout, al-Saftawi insisted on trying to chart a new path for coverage of Gaza in international media, a way for the world to understand Palestine not only as a political idea but as a lived reality. This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

Lakshmi Padmanabhan: How did you start capturing images of life in Gaza? Can you locate us within the political history of that moment?

Jehad al-Saftawi: It started with my phone. Around 2005, camera phones became more easily available in Gaza. It was also a moment when there was a lot of military activity in the neighborhood. Hamas was coming to power and their presence was more visible around the city. I watched well-armed militia members in masks patrolling the streets in my neighborhood at night. But at the time, I didn’t really see that as a direct influence on my interest in photography. I remember shooting a lot of videos with my phone of airstrikes, but also daily encounters at school or at home.

Every resident of Gaza has stories of surviving the airstrikes and the violence they have witnessed. This is just a normal fact of life there and we exchange stories of the things we’ve seen. For me, photography was a way to make these memories into a physical archive that I could return to, to be able to speak about these moments that we were all witnessing. I didn’t begin as a photojournalist, I began from a personal desire to frame and understand my world.

LP: What were your aims when you started sharing your photographs with outlets like Al Jazeera?

JaS: For me, at the time, it was about telling stories of day-to-day survival. How were people still managing to get water, to put food on the table, and to maintain a sense of hope in the midst of horrific violence, of losing loved ones, of watching the political situation worsen? These were the questions I was grappling with as we survived the military attacks in 2008, 2012, and 2014.

It’s important to say that I could do this work because my family was relatively well-off. I didn’t have to worry about how to find food or immediate employment. So I went around speaking to people, documenting their lives. After each military operation, I saw the conditions of misery of people around me, even as Gaza’s political leaders tried to justify what had happened. Initially, I was just trying to help in any way I could. Through documenting the war, I began to question the way I was raised and the stories that we tell about what the point of all this suffering was.

LP: Could you say more about the personal stories that you learned to question through your coverage of the war? You also mention your family’s history in Palestinian politics in your introduction to the book. How has it shaped your work?

JaS: This question of family is at the core of the situation on the ground. I was raised with the awareness that each of us had a responsibility: to devote yourself to the liberation of your people and to the liberation of the land. And the way to achieve these goals was through being of service to my family and to God: to regularly go to the mosque, to study hard but only what is prescribed to me, to be in close connection with my family. My father had been in jail for many years, and we understood that he had made this sacrifice for his principles and that, as his children, we had to carry them on. He would call once or twice a month and only ask us about how often we had gone to the mosque, or how well-behaved and religiously observant we were.

It was in my final year of high school, 2008, that I began to think critically about my father’s attitude toward us. I was trying to start a band with some friends and got in a lot of trouble for this small activity. My mother was raising us to discover our skills and our paths in life, while my father only paid attention to our faith and duty, and not really about us as such. Putting my relationship with him in the broader context of the problem of patriarchy, and how we children were raised to fear and respect our father but never question him—that got me to ask how our political beliefs had come to be a matter of such faith, which we were never allowed to question. Eventually, everything that I had been taught as a clear picture of right and wrong, our roles in it—all of that felt corrupt. Especially in 2008, when I began documenting the siege and the military attacks, it all felt pointless. All that was left was the suffering of my people, the suffering of my generation.

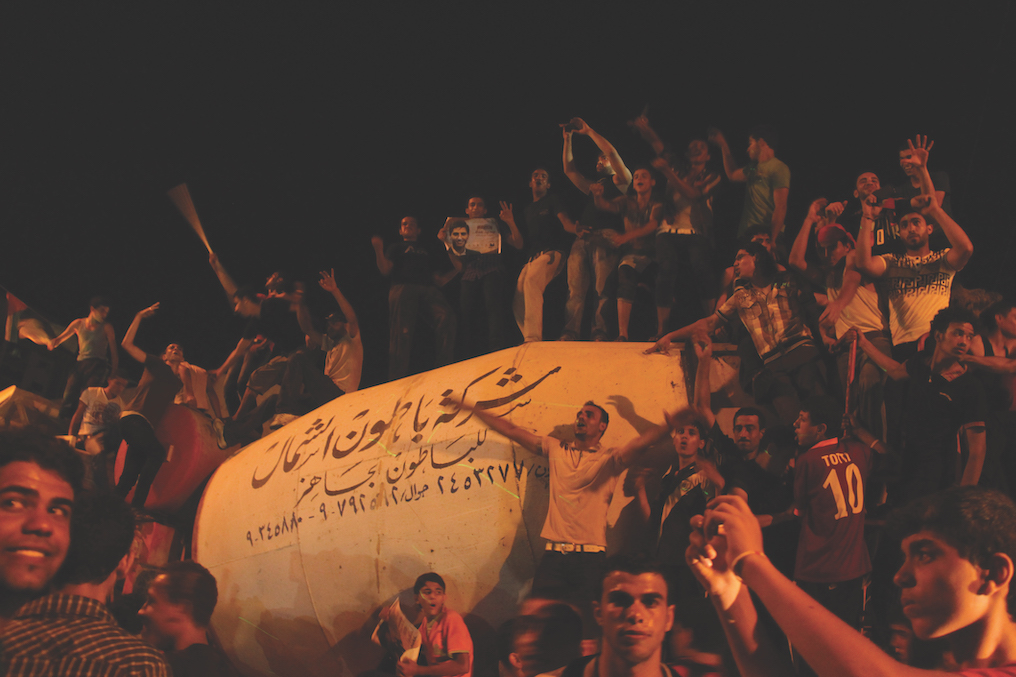

LP: Your photographs reflect this fraught relationship between everyday domestic life and these broad political questions about duty, national identity, and community. I’m thinking of this scene of celebration, which occurred on the night in 2013 when the Palestinian singer Mohammed Assaf won Arab Idol. It was also a night on which you were interrogated for taking these photographs of the celebrations in the city. Tell us about that night.

JaS: My wife Lara and I were at home when the winner was announced, and we expected there to be celebrations in the streets. People had already been celebrating his progress through the competition. So we ran out, and I grabbed my camera to document the occasion. We saw people streaming together even as we saw a fair amount of police presence on the streets.

Within a few minutes, I was stopped and questioned. It wasn’t a surprise: I had come to expect a certain suspicion from the cops for holding a camera; they often stopped me with questions about who I worked for or why I was out taking photographs. But there was another reason, too, that we expected to be stopped. We were sharing in the excitement of the people around us, and we knew our joy would get us in trouble. Any kind of celebration that wasn’t strictly in line with Hamas’s religious views was beyond the acceptable limits of public life for the police. There is this constant fear of enjoying even the smallest crumbs of an ordinary life—singing, dancing, these celebrations in the streets—because any images of such celebration that circulate might be seen as religiously inappropriate and lead to the loss of political and economic support for Hamas.

LP: Your images give us a view into the intimate geography of Gaza City sites of gathering and routes of travel. One of these sites that is extremely important to the survival of Gaza is the Rafah tunnels. Could you talk about this site and the images of it in the book?

JaS: By the end of 2006, the fighting in Gaza and the siege imposed by Israel had made our lives truly intolerable. Israel completely cut off supplies of the most basic necessities into the city; even for those of us who had money to buy goods, there was nothing left beyond rice and flour. The tunnels had existed for a long time, but now they became our lifeline. I think it was in 2008 that we started to see more Egyptian goods enter Gaza through them, and finally we started to have more groceries and basic necessities like soap and laundry detergent. We heard stories of people crossing into Egypt to do their grocery shopping and coming back. At the time, Hamas seemed to be on good terms with the Egyptian government, and guards were willing to look away as long as we remained discreet.

The pictures you see here are from 2010 and 2011. By then, the tunnels were more strictly regulated and I had to get permission from the Hamas Ministry of Interior to get access. Some remain blocked off for military use. As you see in this image, the Egyptian guard tower is right by the entrance to the tunnels, and so we needed their soldiers to ignore these activities since this is such a vulnerable location.

LP: One theme that recurs in your stories of life in Gaza is the position of ordinary people, who have to negotiate with the local government, Egyptian soldiers at the border, and the Israeli military. Can you talk a bit about how people in Gaza negotiate multiple political regimes?

JaS: Let me address your question about the political scenario with an example. As I said earlier, once Hamas took over, the siege that followed made life in Gaza truly horrendous. We were in total economic and social paralysis. At one point, Palestinians tried to break down the metal barrier at the border with Egypt out of absolute desperation, we literally didn’t have any options to care for ourselves without provisions. Somehow, early in 2008, people managed to cut through the metal and went through. The first people who made it through were immediately shot and killed by the Egyptian soldiers on the other side. But then people started to pour through. For a brief moment, maybe a couple of days, there were hundreds of thousands of people going across the border. I went too, with some of my family. Palestinians went to the markets in Egypt, bought food and even livestock and ran back to their families. I think we spent about half a day walking through the border towns in Egypt. Eventually, the Egyptian authorities put a stop to it, but I think the reason they were willing to turn a blind eye to the tunnels, or to goods coming into Gaza, was to avoid more of these kinds of large-scale uprisings at the border. It wasn’t like we were trying to smuggle weapons; people just needed food and medicine. This was the status quo until around 2013, when political relations between Hamas and Egypt deteriorated again.

LP: I’m curious about this image you took on July 16th, 2014. In it, we can see people hiding behind a building but peering at the camera, waiting for a bomb to strike. This implies that they had advance warning about this attack from someone in the Israeli military. You appear to be standing in the place where the bombs are about to land, so there is a sense of physical danger and yet there is also this eerie calm before the violence. Could you talk about how this image came to be?

JaS: I took this image in 2014 during the war [Operation Protective Edge] that began that summer. I came to this neighborhood because it had been bombarded the night before. The family of a prominent member of Hamas lived there, and I think around 25 or 30 people were killed from that family. So I was there to document the aftermath, and I heard neighbors shouting that another attack was imminent because they had received a call, perhaps from the Israeli military. I’ve seen photographers try to capture images of the missiles, to document the attack. But I was struck by the reactions of people to the scene: that they had chosen to stay here and watch rather than hide indoors. Perhaps they were getting some sense of security by being able to see what was happening.

LP: Could you discuss the few images you’ve taken indoors, the ones of your own family at home? This one from March 8th, 2015 is of Lara and your brother Hamza in your apartment, which might be seen as inappropriate because the photograph conveys a sense of casual intimacy. You note that some of these photographs couldn’t be viewed in public if you still lived in Gaza. Can you explain this tension?

JaS: I think that image of Lara and Hamza captures a lot of contradictions of our lives. Everyone in Gaza is in prison, struggling to survive the political siege that denies us access to basic goods and services, while also being silenced by the conservative religious norms that Hamas has violently policed. If you are a son, you still have a margin of freedom, even with all these political and religious limitations. But when we got married, Lara and I found ourselves rebelling against these norms, which made us feel like prisoners even inside our home. I think that picture itself is a document of our small struggles, how we learned to think beyond those restrictions and live in ways that felt true to us after everything we had witnessed in the years of living in the war zone.

I can tell you similar stories about my sister’s struggles within the family. There is an image of her early in the book because I also want her story to be told, and to address the way that my extended family punished her, a young girl, for small acts that they felt were unacceptable, like making a social media account. These are ongoing conversations and occasional fights with my mother, who was doing her best to raise us, yet didn’t want to cause more trouble, especially with the men in the family.

LP: As you take stock of your work in Gaza until 2016, and your experience of the last couple of years in the United States, what are your thoughts now about the stories in the book and the narratives you want to tell moving forward?

JaS: I hope what I’m doing is providing a kind of self-reflexive criticism rooted in my love for my people. First, I really want the generation of children growing up there now to not be normalized to the military presence, or to accept our schools and mosques as potential targets of an attack. I know that hundreds of thousands of people in Gaza are all dreaming of a better life, beyond the boundaries of a tiny strip of land.

I’ve seen how those who have political power in Gaza are fighting to control every aspect of our lives there, and only fueling hatred. And they are especially opposed to any forms of dissent or calls for change. No one is allowed to question the authority of the ruling government, and I’m so frustrated with that reality. A few months ago, for example, Rami Aman, a peace activist working in Gaza, was arrested along with seven others. His crime was that he spoke to Israeli peace activists on a Zoom call, just as we’re speaking right now. This is how you ensure that thousands of young people can only take the path of military training and violence.

When we speak about Gaza, there are generally two perspectives. The racist one is that everyone there is a terrorist working to kill Jewish people. The other view is that the people of Gaza are the most heroic and resilient, capable of endlessly fighting for their freedom. The point of my work is to refuse these two options. Gazans are just normal people, trying to survive in a world where political leaders from all sides are stripping them of their ability to live normal lives.

I think the responsibility for anyone trying to help the cause of the people of Gaza is to not reproduce these simplistic views. And I do have greater expectations from left-wing or more progressive media. I think stories that try to defend the violence, even when they’re trying to paint a picture of the heroic Palestinian fighter, end up legitimizing the minoritarian rule of Hamas, which does not speak for all the people of Gaza, and often treats the lives of ordinary citizens as disposable in this war. We’re now at a moment where Hamas has succeeded in normalizing an extremely high level of violence as a daily condition of existence, and people think the only way to oppose the Israeli occupation is through the tactics that Hamas has been pursuing, which is just not true. I really want progressive news outlets to pay attention to people outside of these state actors—to talk to everyday people and tell their stories. And I hope my book does that too.

Lakshmi Padmanabhan is an assistant professor in the Department of Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University in Chicago.