Newsletter

Aug

18

2022

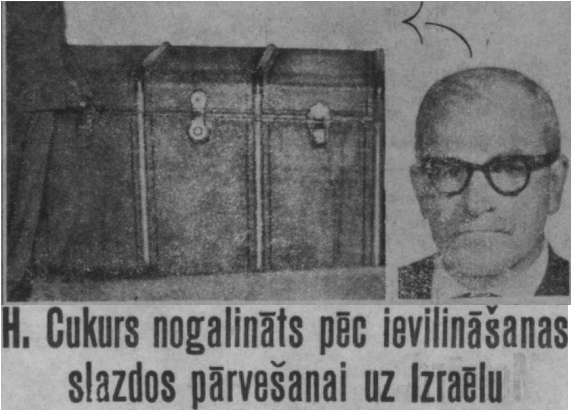

A March 1965 report from the Latvian newspaper Laiks on the circumstances of Herbert Cukurs’s murder, suggesting he was lured into a trap intended to transport him to Israel.

August 18th, 2022

Dear Readers,

This week’s newsletter is a conversation between two Jewish Currents contributing writers, Helen Betya Rubinstein and Linda Kinstler, about the latter’s debut book, Come to This Court and Cry: How the Holocaust Ends, a reported account of the posthumous trial of a Latvian Nazi collaborator that comes out this month in the United States. The book is also an investigation into Linda’s family history, which includes both perpetrators and survivors of the Holocaust, and the culmination of her years of thinking about Holocaust memory as a PhD candidate in rhetoric at UC Berkeley. You can see Linda in conversation about the book with Jewish Currents Executive Editor Nora Caplan-Bricker at Harvard Book Store in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on September 12th (sign up here).

Best,

David Klion

Newsletter Editor

Jewish Currents readers may be familiar with Linda Kinstler’s exquisite reporting on the “memorial chaos” of Babi Yar and the “posthumous trial[s] of history” in Poland. Her new book, Come to This Court and Cry: How the Holocaust Ends, takes on similarly knotty matters of history and remembrance as they play out in yet another complicated post-Communist context: her parents’ native Latvia. The book traces the case of Herbert Cukurs, who “bears the ignominious honor of being the only Nazi whom the Israeli Intelligence Agency, Mossad, is known to have assassinated.” A member of Latvia’s Arājs Kommando killing unit—which, among other atrocities, was responsible for the murder of 25,000 Jews in the forest of Rumbula in the winter of 1941—Cukurs was known before the war as a “Latvian Lindbergh” and has been understood more recently as a sort of Latvian Adolf Eichmann. His grisly 1965 murder was orchestrated by the same agent who handled the logistics of Eichmann’s 1960 abduction, Yaakov Meidad. But Cukurs was killed before any trial took place, leaving his official legacy in a kind of permanent limbo. His posthumous 21st-century trial by the Latvian Prosecutor General forms the spine of Kinstler’s book. “I could not think of this case as anything but a curious continuation of the celebrated proceedings in Jerusalem, a ghostly successor to that ‘world trial,’” she writes, alluding to the famous reporting of Hannah Arendt.

Kinstler also has a more personal connection to the trial: Her “dead, disappeared” paternal grandfather worked alongside Cukurs as a fellow member of the Arājs Kommando—though he was also, possibly, a Soviet spy. He vanished in an alleged suicide before her father was born; one novelization of Cukurs’s death, You Will Never Kill Him, suggests that he was part of a plot to kidnap Cukurs for the Soviet state. Meanwhile, Kinstler’s mother’s side of the family, Jews originally from Kharkiv, Ukraine, mostly survived the Holocaust—the women because they were evacuated beyond the front lines of the Nazi invasion to Soviet Kazakhstan, the men by fighting in the Soviet Army. The unresolvable questions of her paternal line run up against the Jewish experiences of her maternal family, sharpening the felt experience of those stubborn holes in the Cukurs case. She traces its twists and turns with patience, care, and a burning sense of integrity, bringing the reader into an answerless place between conflicting witness testimonies, between history and literary narratives, and between what is recorded as evidence and what is otherwise passed down or felt.

Kinstler’s research is animated by the question Yosef Yerushalmi poses in the postscript of his monumental study of Jewish history and memory, Zakhor: “Is it possible that the antonym of forgetting is not ‘remembering,’ but justice?” Whereas in Eichmann’s case, “Vengeance could not come at the cost of justice”—this was why he “had to be kept alive”—here we’re left wondering whether, indeed, the vengeance wrought by Cukurs’s murder might prevent justice from having the final word.

Helen Betya Rubinstein: In your prologue, you write that the book’s subtitle, “How the Holocaust Ends,” is intended as “a warning.” What do you mean by that?

Linda Kinstler: The idea that there would be an “end” to the period in which the Holocaust belongs to living memory has always been a source of anxiety, and for good reason. I was interested in interrogating what that long ending looks like, and in articulating some of the perversities that it has produced. That was why I found myself drawn to this strange office in southwestern Germany, the Central Office for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes, which is a literal instantiation of the idea of an “end” to this period, because it is legally obligated to continue investigating Nazi crimes until there are no living perpetrators left. For the past several years, the press has been saying that the office will shut down any time now, that every director is the “last” director. And yet it persists, even as its investigators are keenly aware of the fact that they are always running up against a “deadline” in a very literal sense of the word.

The idea of an “ending” also speaks to the literary and legal dimensions of the book. One of my animating questions is: What does a trial do? What does it mean when the possibility of a formal legal proceeding is foreclosed, when the “ending” provided by a verdict is indefinitely deferred? The assassination of a Nazi is one kind of ending, and we see how that extrajudicial killing opens the door not only to conspiracy theories but also to its own tangled legal trajectory that remains under investigation. Nuremberg and Eichmann provide the “endings” that readers are perhaps most familiar with, though the relation between these two world-historical trials illustrates how they, too, do not provide closure: Eichmann’s name came to the attention of prosecutors at Nuremberg; his kidnapping and trial were in many ways conducted as a response to Nuremberg, as were the domestic German prosecutions. Eichmann’s trial, of course, helps set the stage for Cukurs’s assassination. There is a wonderful Israeli documentary about Eichmann’s hangman, called Hatalyan, that the legal scholar Itamar Mann writes about. Its subject, the Sephardi prison guard who was ultimately tasked with killing Eichmann, was so haunted by nightmares after the fact that he embraced Orthodoxy and started working as a kosher butcher.

I think the moment that best illustrates what I mean by the subtitle comes from the archive: I found a letter from a Riga survivor named Joseph Berman, who was asked to identify SS officers who served in the Riga Ghetto, then in custody in a West German court. One of the officers asked to speak to Berman privately. He got down on his knees and begged to be forgiven and for Berman to help him escape with his life. Berman said he was prepared to help him, provided that he confessed to everything he had done, from “A to Z.” They shared a cigarette, they embraced. And then Berman writes: “How would I know when it is ‘Z’?” Even if the man confesses, there is no way to know if that is the whole of it.

HBR: Your book dramatizes how the absence of survivors literally means an absence of witnesses, in a legal as well as a historical sense. As Edward Anders, a survivor of the Holocaust from Liepaja who emerges as one of your main characters, put it in an email to you: “Dead men tell no tales, but survivors do.” Did working on this project shift your sense of the role of survivor testimony? What did you learn from working with Anders, whose scrupulous and near-scientific approach to this history includes a formula attempting “to calculate precisely how many Latvians actually wanted to expose Jews in hiding and lead them to their deaths”?

LK: Edward Anders, formerly Alperovich, is constitutionally allergic to any embellishments, inaccuracies, or unfairnesses, and his methodical way of approaching this history was an inspiration—and a kind of warning. He is absolutely unromantic about the possibilities of capital-J “Justice,” perhaps because of his experience watching his own testimony be excluded from the evidentiary record at Nuremberg, and then collecting survivor testimonies for trials that ultimately never happened. I was deeply moved by his commitment to exposing the truth in other ways, be it through memorials, memoirs, museums, or what have you. Where law fails, we turn to culture to pick up the slack.

Anders occupies the role of survivor in an entirely original way—he refuses to testify in the Cukurs case because he wasn’t an eyewitness to Cukurs’s wartime activities, but also because he does not believe in the utility of this unconventional, posthumous legal process to begin with. What are we to make of this refusal? We expect survivors to speak, to offer us their words, to relive what they have been through in service of the present. What happens when they say “no thank you”? This question has been posed for decades—Maurice Blanchot wrote about it in The Last Man—but I think we have yet to take it seriously. Instead, we make holograms of the survivors so they can keep “speaking” in their afterlives—so their words can be endlessly circulated and replayed and algorithmically regenerated.

HBR: In many post-Communist states, Holocaust memory gets instrumentalized in peculiar and often conflicting ways. Jelena Subotić’s book Yellow Star, Red Star argues that historical revisionism often results from an “ontological insecurity” about national identity.

LK: “Ontological insecurity” is such a rich phrase. It speaks to how this particular period of history has become, for many Eastern European nations, a kind of unsolvable Rubik’s cube; it can be configured and reconfigured in a million different ways, all of them uneven and unsatisfactory because no amount of memorialization can stand in for, or make up for, all that has been erased. And yet, there’s a strong desire, even a need, to find the absent piece and arrive at a clean and complete ending, to fill in the void. This is one of the many reasons I was so drawn to the philosopher Marc Nichanian’s work, which points out the abiding perversity of the insistence that the very people whose families and histories were obliterated must also be the ones to prove the fact of their own loss. It’s a cruelly unending pattern: The denialist denies, the survivor stands up and points to the void where someone once existed—knowing that the denialism will continue, but morally, emotionally, heroically compelled to stand up nevertheless.

For me, the case of Cukurs became a way of interrogating this epistemological crisis. The facts required so much unwinding: you have an assassinated man being posthumously investigated for participating in well-documented instances of genocide and war crimes. There are testimonies that identify him at the scenes of the crimes, there are interrogation records that speak to his presence. But because the survivors who gave those testimonies are dead, and because it was a dead political regime—the Soviet Union—that conducted the interrogations, the prosecutors can decide that, actually, there is no admissible evidence. Oh well! Case closed, puzzle solved. Except not quite: The Latvian Jewish community filed an appeal, they found the last living survivors—who were less likely to be impugned simply because they are still among us—and they called the children of the dead survivors and asked them to act as their legal stand-ins.

Somewhere along the way, I started thinking about the book as a story of nationhood, about the narratives that nations fight and kill to secure for themselves. The fact that Johann Gottfried Herder came up with the term “nationalism” after riding through the Latvian countryside and collecting folk songs—what Latvians call “dainas,” four-line poems—was something I kept returning to, the origin point of a now-antiquated imagination of romantic nationalism anchored in language and storytelling rather than in blood or creed. There’s also the Israeli side of the story: Yaakov Meidad wrote a fascinating pseudonymous memoir about the Cukurs mission that explicitly connects it to both the Nuremberg and Eichmann trials. In the preface, the former head of Mossad writes, “Eichmann was not the only one,” and that, “We have before us a fascinating book, based on real facts—a classic case of truth being stranger than fiction.” The narrative is “based on real facts,” but there is a suggestion that some fictions might have slipped in. We know that the Eichmann trial was, among many other things, a nation-building exercise, a way of consecrating the new Israeli state and its laws, which is why David Ben-Gurion insisted upon a public, televised proceeding. By contrast, the assassination of Cukurs was a footnote in the international press, the gruesome photos of his corpse noted and then quickly forgotten. Now, he is finally getting his proverbial trial, though not in the way that Meidad envisioned. Testimony from the Eichmann trial was submitted to the Latvian prosecutor general for consideration These two cases are so deeply entwined, and yet one is world-historical, the other almost completely unknown.

HBR: I was struck, reading, by two “nevers” that appear in the book: One in the name of the team of Mossad agents that assassinated Cukurs, who called themselves “Those Who Will Never Forget,” and one in the title of Armands Puče’s bad-faith, neo-nationalist novel about Cukurs’ fate, You Will Never Kill Him. The desire for finality expressed in those “nevers” is so strong. I want to say it has to do with justice, with the desire for a genuine “case closed, puzzle solved.” But your book refuses the reader the finality that a fictionalization might offer.

LK: The great irony that your question exposes is that while both of these “nevers” evince a desire for finality, they both undo their own desires in a way. Both the Mossad memoir and the Latvian novel forced me to be attuned to questions of genre from the very beginning—these are my source texts, both fictionalized accounts that nevertheless claim to be “based in fact,” both of which have been parsed by lawyers for clues to this curious case. Both are undeniably products of different nationalist agendas, and both mobilize the tropes of spy novels to tell their stories. Their “nevers” illustrate part of why Yerushalmi was so unsatisfied with positioning forgetting as the antonym of remembering. Simply transmitting a memory is not the same as ensuring that the truth of the thing in question is remembered—memory can entrap, corrode, grow stale. I like to think that’s why he was so struck by the phrasing of the Le Monde questionnaire [that inspired his question], which asked readers to say if it was “forgetting” or “justice” that most characterized their attitude to the period of the war and occupation. And of course, I just love his line about this phrase: “Can it be that the journalists perhaps stumbled across something more important than they perhaps realized?” Maybe the journalists got it right!

HBR: You open with the declaration that your own book is “not a spy novel”—instead, “it leans into the great unknown”—and it carefully attends to narrative genres, including the legal, the literary, and the historical. Given that the book is, in some sense, a detective story, how did you ensure that your narrative maintained its aesthetic and historical integrity?

LK: The film director and theorist Sergei Eisenstein—who was born in Riga—wrote that “any detective novel, regardless of its story, is for every reader, above all, a novel about himself: about what happened to the reader as a human individual in general; as an individual developing from a child into an adult; as a living being who experiences continuous transitions ‘there and back,’ from layer to layer of consciousness.” In writing and talking about the book, I’m reluctant to talk about myself and my own role in the narrative—Eisenstein’s line captures it all. When I started following the story, it’s not that I was naive about the world that I was stepping into, but I definitely didn’t realize how thoroughly it would entangle me or define nearly a decade of my life. I’m not sure I would have followed through had I not been young and kind of blindly curious—curious about my own family history, about the world my parents came from and fled, and about how that world intersected with various historical moments that I had studied in seminar rooms, not yet realizing that they still exerted a pull over so many people’s lives, including eventually my own.