Newsletter

Nov

17

2022

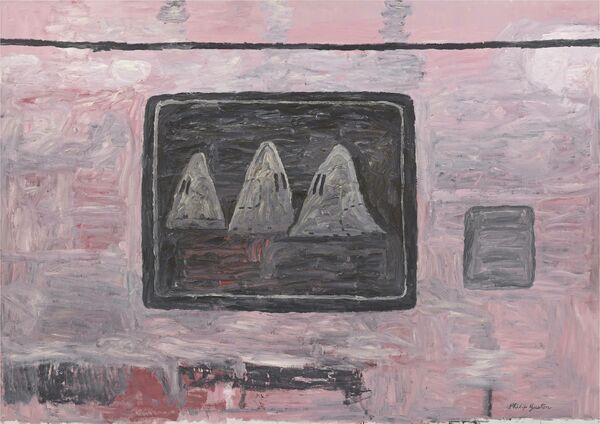

Philip Guston: Blackboard, 1969, oil on canvas, 201.9 x 284.5 in. © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

November 17th, 2022

Dear Reader,

In the fall of 2020, in response to the global anti-racist uprising following the murder of George Floyd, four major art museums announced that Philip Guston Now, a collaborative retrospective of the late painter’s work, would be postponed until 2024. Though no one had protested the planned exhibition, the organizers were concerned that it would stir up controversy because of the inclusion of Guston’s illustrations of members of the Ku Klux Klan. While Guston was Jewish, and most critics understand these pieces to be condemning the white supremacists they depict, many of the works are rendered with an unsettling cuteness and a disturbing sense of mundanity as they show the Klan members smoking, chatting, and driving around.

The curators worried that without proper contextualization, an audience newly attuned to the pervasiveness of anti-Black racism would take offense. “We have a responsibility to meet the very real urgencies of the moment,” the museum directors wrote in a joint statement. “We feel it is necessary to reframe our programming and, in this case, step back, and bring in additional perspectives and voices to shape how we present Guston’s work to our public . . . We plan to rebuild the retrospective with time to consider the many important issues the work raises.” This May, after nearly two years of revisions, Philip Guston Now opened at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, its postponement truncated in response to broad outcry from the art world; it has now moved to the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and will make its way to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Tate Modern in London over the course of the next year.

For this week’s newsletter, we wanted to highlight contributing writer Zoé Samudzi’s searing review of the exhibition. Zoé examines how the show, rather than helping the audience understand the richness of Guston’s art and its politics, sidelines the most interesting parts of his oeuvre—including the Klan paintings—and tacitly invites viewers to turn away from their discomfort, rather than to learn from it. By leading us through a rich exploration of Guston’s capacious body of work, Zoé reveals how his white-hooded figures show him wrestling with the contradictions of being a white Jew—vulnerable to the violence of white supremacy while also complicit in it. Along the way, she raises profound and far-reaching questions about the risks of art institutions prioritizing sensitivity over engagement with difficult subjects. As she writes, “It is impossible to be both honest about race and universally inoffensive.”

Best,

Nathan Goldman

Managing Editor

It’s not always advantageous for an

exhibition’s reputation to precede it. If critical consensus or

controversy about a show’s contents can build anticipation, it can also

stand between viewers and the works before them, teaching them to see

only what they expect. But it’s all the more disconcerting when the

exhibit itself preemptively shapes attendees’ affective responses.

Before entering the Philip Guston Now retrospective, which

closed at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in September and is on view until

January at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, audiences are invited to

take a printed handout: an “Emotional Preparedness Guide” featuring

comments from a trauma consultant who advised the show’s curatorial

team.

“It is human to shy away from or ignore what makes us uncomfortable,” the flyer begins, “but this practice unintentionally causes harm.” It then encourages museumgoers to “lean into the discomfort of confronting racism on an experiential level,” a process aided by the pursuit of “self-care, rest, education, and community.” The boilerplate social justice language seems designed to facilitate an encounter with violent content while acknowledging its potential to cause distress. But if the warning appears defensive, there’s a reason: It points directly to a previous institutional error. Two years ago, the museums organizing the show made the controversial decision to postpone it on the grounds that the racial imagery in Guston’s work required “additional perspectives and voices” to give it context. Philip Guston Now is their floundering attempt to do so.