DRESSED IN MATCHING white crop tops, the Alpha Gun Angels arrived 20 minutes late to the opening ceremony of Israel’s Defense, Homeland Security and Cyber Exhibition (ISDEF), just as Major General Danny Yotam, former director of the Mossad, welcomed the crowd. The hot June sun beat down on the gray strip of asphalt outside Tel Aviv’s convention center, where heads of state, national security agencies, police forces, and private defense corporations sat sweating in awkwardly small black plastic chairs.

The Alpha Gun Angels ignored the ceremony and headed directly to the Harley Davidson Display inside the air-conditioned lobby, where they posed on motorcycles and fondled sniper rifles manufactured by the Israeli company MeProLite. Their impossibly long glossy hair was luminescent under the fluorescent overhead lights. A bearded man in a t-shirt printed with the Angels’ slogan—“Fire Up Your Marketing!”—live-streamed the scene to hundreds of thousands of Instagram followers on an iPhoneX. A group of counter-protesters locked outside the front gates called for an end to Israeli arms exports through a megaphone. Their chants drifted through the humid summer air.

The Alpha Gun Angels, who bill themselves as Israel’s premier gun-modeling and social media–marketing agency, are a team of nine active and veteran IDF combat soldiers turned Instagram celebrities. On social media, the Angels market their combat experience as a sexy lifestyle brand, turning Israeli militarism into a generic but alluring image to be sold to gun companies, militaries, police forces, and gun rights advocacy groups around the world. This year, the Angels were at ISDEF projecting eroticism at a discordant combination of registers, crossing the sultriness of Megan Fox in Transformers with the libidinal thrust of Channing Tatum in White House Down. “Alpha Gun Angels” isn’t that much of a mouthful, but the group sometimes just brands itself as the AGA, simultaneously connoting the faceless severity of a government agency (think NSA) and the arch professionalism of a talent management firm (think IMG Models). At the conference, their popularity was manifest—the line of cybersecurity specialists and army generals waiting for autographed photos snaked all the way around the booth of an Israeli spyware developer 100 feet away.

As the crowd dispersed inside the exposition hall, some Angels posed for photos with the latest in offensive weaponry and combat accessories: shooting gloves used by Israeli combat troops, minuscule CCTV helmet-cameras tested by Colombian counterinsurgency units, compact drones equipped with AI technology. Meanwhile, several Angels handed out brochures listing their Instagram handles, number of social media followers, clothing and shoe sizes, and bust and butt measurements. Their brochures find them splattered in dirt and fake blood, crawling out of thorny bushes in an ambiguous desert setting, as if Charlie’s Angels had joined the Mossad.

ISDEF TAKES PLACE every other year in Tel Aviv. For Israel, a country whose economy rests heavily on its defense and security sector, the expo is an important business opportunity; in 2018, Israel’s arms exports were the eighth largest in the world. Over the course of three days, 15,000 participants from 90 countries circulated around exposition booths selling everything from bedazzled combat boots to tiny recording devices embedded in fake sticks of gum. Intensifying the sci-fi dystopia vibe, archival footage of news anchors breaking reports of terrorist attacks played in an endless loop on an enormous TV monitor as miniscule drones darted overhead. A roped-off corner of the exhibition area was converted into a lecture hall, where Israeli generals and American CEOs of cybersecurity firms shared counterinsurgency tactics and digital-warfare strategies with military and police delegates from India, Sudan, and China.

Israel’s role in the global defense and security industry has assumed an unprecedented scale of visibility in the years since the Second Intifada, the Palestinian uprising that ended in 2005. The growth of occupation infrastructure—separation walls, checkpoints, segregated highways—throughout the Palestinian territories expanded the testing grounds of Israeli defense and security products. While Israel still relies heavily on arms imported from the US, a ballooning number of Israeli companies now produce the weapons and technologies used to enforce the country’s apparatus of control over Palestinian lands and people. On display in Tel Aviv’s exposition hall was an array of Israeli manufactured technologies: Israel Weapon Industry’s X95 assault rifle, wielded by soldiers patrolling Hebron’s old city; Camero’s infrared “through the wall” sensors, used during the IDF’s counterinsurgency operations in Gaza; and the NSO Group’s covert cybertechnology, notoriously sold to Saudi Arabia to hack the phone of the late Jamal Khashoggi.

In recent years, academics, journalists, and activists have condemned how exposition spaces like ISDEF represent Palestine as a laboratory—a sealed space where Israeli defense and security products can be tested out before hitting a global market. Israeli-manufactured weapons and technological systems are often branded as “combat-proven” and “battle-tested,” turning the notoriety of a more-than-50-year occupation into a marketing strategy.

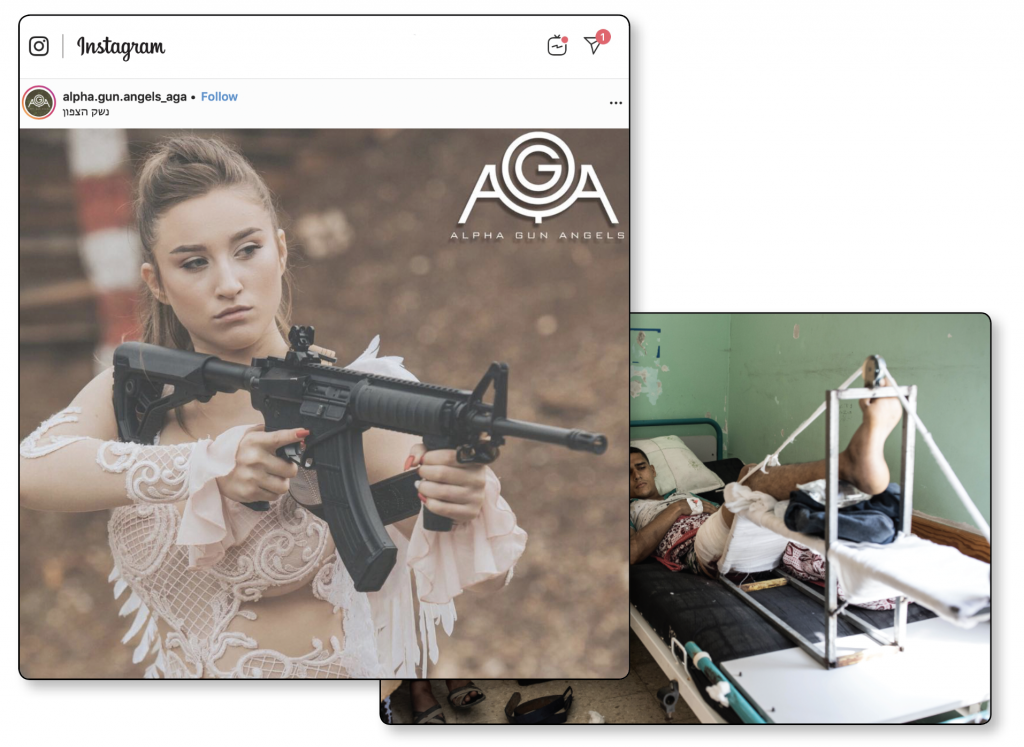

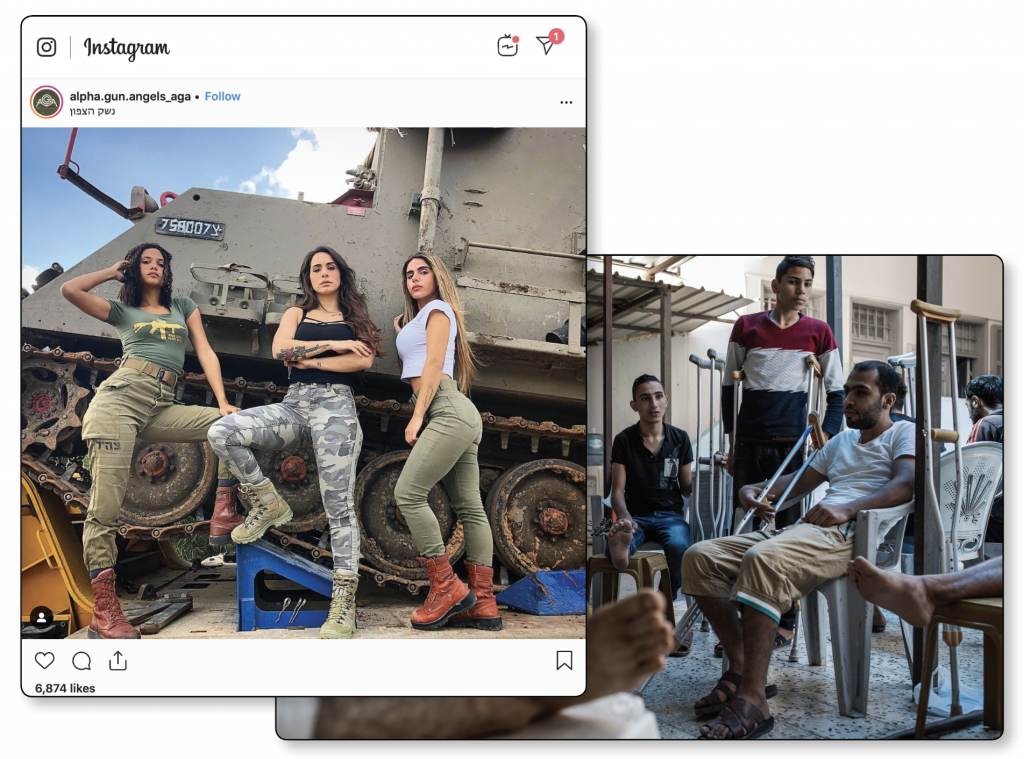

But while the Alpha Gun Angels weren’t the only angels in the ISDEF exposition hall—also advertised on the convention floor was Israel Aerospace Industries’ Gabriel missile; Mifram Security’s mobile Gabriel shelter; and Seraphim Optronics’ semi-manned surveillance systems, named for archangels Gabriel, Raphael, and Ariel—the AGA were selling something different. On their brochures, the Angels’ social media fame took center stage: Natalia Fadeev (120,000 followers; Bust: 98 cm, Waist: 70 cm) appears in a white lace minidress and angel wings set off by the black strap of an assault rifle; Orin Julie (600,000 followers; Bust: 88 cm, Waist: 61 cm) walks through hilly terrain in a camo sports bra with a string of ammunition slung across her chest; Nina Nature (100,000 followers; Bust: 90 cm, Waist: 60 cm) leans against an army tank in a tight black bodysuit grasping the barrel of an AK-47 in one hand. Three angels pose in denim shorts and crop tops, pointing sniper rifles at the camera in front of a large concrete barrier; five angels in white or pale pink sequined ball gowns and angel wings perch on a dirt mound gripping assault rifles.

Spinning vague signifiers of Israeli military infrastructure—an unmarked tank, an electric fence, a concrete barrier—into social media fame, the Angels render Israeli militarism sanitized, sexy, and saleable, effacing the specific, lethal effects of its defense and security apparatus. It doesn’t matter what the gun or combat accessory can do or has done to occupied people. It just matters that the Angels look good doing it.

THE ALPHA GUN ANGELS were founded in 2018 by Orin Julie, 25, who calls herself “Queen of the Angels.” Julie is an IDF combat veteran, shooting instructor, fitness model, and Instagram celebrity. She began modeling for gun companies during her time in the IDF’s Search and Rescue Unit, where she served as a communications sergeant. During her service, Julie filled her Instagram grid with sexy selfies and IDF-issued rifles, attracting hundreds of thousands of followers. By Orin’s account, her military background set her apart from other Instagram gun models and won her popularity among American gun enthusiasts: “I know how to hold guns, how to shoot, how to do combat stuff—and Americans appreciate that,” she told the Times of Israel. She was quickly recruited to promote the Israeli gun and tactical gear company Zahal, as an influencer, tagging the brand alongside #idf, #israel, #searchandrescue, and #armylife in selfies snapped from inside a tank or on military bases. Her photos were often accompanied by captions punctuated by flag emojis, promoting American-style gun rights rhetoric alongside Israeli nationalism: “no matter how hard it’ll be WE WILL DEFEND OUR LAND!” or “#gunsdontkillpeople #secondamendment.”

After she was discharged from the army, Julie got a tattoo of an assault rifle on her forearm and decided to turn her viral online presence into a business. She enlisted other young Israeli women—all active or veteran combat soldiers from the IDF—to become Angels, modeling for clients like the IDF, ISDEF, Machine Gun America, Elbit Systems, and Israeli Weapon Industries. The median age of AGA’s models is 22. A quick foray through their official Instagram page shows the Angels posing on shooting ranges, at gun shows, and inside weapons expos throughout Israel and the United States, from the NRA’s annual convention in Indianapolis to army bases in the Negev Desert.

There is, of course, a long history of states glorifying militarism with sexualized images of women, from the US’s popularization of pinup military propaganda during the First World War to provocative state-issued photographs of Israeli women soldiers, published in the 1950s and ’60s, that framed military service as pleasurable rather than merely compulsory. But today, social media and a transnational private defense industry have democratized the lusty aesthetics of warfare. Gun influencers on Instagram are on the rise; recent reporting from Vox suggests that, in the US and Canada, they often lack active or veteran army status, and are instead contracted primarily with private rifle companies or civil organizations like the NRA. But the trend is the same: beautiful women paid to post sexy selfies to Instagram to market guns, the same way Kylie Jenner sells overpriced matte lipstick. The political agenda is buried beneath the sale of an aspirational lifestyle.

What sets the Angels apart from their North American counterparts, however, is their distinctly Israeli brand of social media militarism. The 2012 attack on Gaza—called Operation Pillar of Defense by the IDF—inaugurated what some have described as a new genre of Israeli militarism: “instawar,” or the spread of military propaganda into social media platforms. The IDF had been pouring resources into developing its social media presence since the 2008 bombardment of Gaza, codenamed Operation Cast Lead, and by 2012 their efforts culminated in a cohesive brand narrative. The IDF’s Twitter account began live-tweeting military operations. Infographics announcing the assassination of high-profile Hamas members crowd its Instagram page, and live footage of the military’s incursion into the Gaza Strip was posted to its YouTube account. IDF social media, meanwhile, elided the human cost of the Israeli airstrikes in Gaza, which took the lives of 175 Palestinians and injured another thousand in just eight days. As the writer Huw Lemmy noted in the early days of this campaign, the curated aesthetics of Israeli militarism spoke to consumers like any other lifestyle brand, “saying ‘we are just like you, and these military decisions are the ones you would take, if you were in our situation.’ ”

In the years since, reframing military occupation as relatable social media content has become a priority for the IDF. As the occupation drags on, images of blasted infrastructure in Gaza and the lethal effects of military operations in the West Bank continue to go viral. The military’s “new media budget,” created within the IDF’s Spokesperson Unit in 2009, intends to combat the expanding threat of bad publicity on social media by vying for control of digital space. While it is now commonplace for militaries to devote portions of their budget and staff to social media operations, the scale of the IDF’s public relations efforts is striking. With 70 officers and 2,000 soldiers managing the military’s press and social media presence, the Spokesperson Unit is one of the largest military PR offices in the world. The result is a multiplatform campaign: on the IDF’s YouTube channel, fresh-faced women combatants talk about feminism in the Air Force; on Twitter, soldiers stroke fighter jets in celebration of Valentine’s Day; on the official Facebook page, a photo of a female trainee appears with the caption “no makeup, just camouflauge.” Today, the IDF has become a leader in propagating military operations as social media white noise.

As opposition to Israel’s occupation echoes across social media platforms, the Angels’ sexy selfies frame Israeli militarism as something to be desired rather than condemned. Alongside the tangible mechanisms of control sold in Tel Aviv’s exposition hall—sniper rifles and surveillance cameras, cyberespionage software and AI augmented drones—AGA exports Israel’s ability to deny violence and normalize occupation by aestheticizing warfare. Dressed up in high heels and detachable angel wings, the eroticism of Israeli obfuscation is now a transnational commodity.

Sophia Goodfriend reports on automated surveillance and digital rights from Tel Aviv. She is a PhD candidate at Duke University.