Material Conditions

Rachel Breen’s textile work connects the garment industry to the suffering that sustains it.

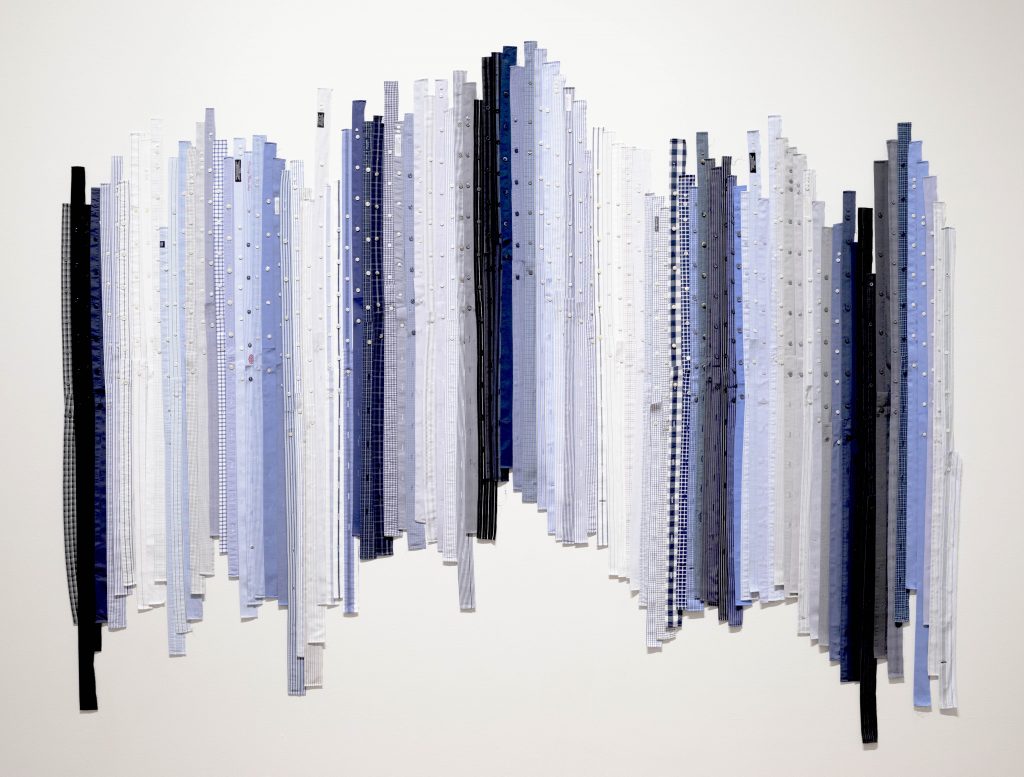

IN THE BOTTOM LINE, textile artist Rachel Breen attached thin strips of blue and gray cloth to a wall, staggered as if describing to a curve on a graph, the movement of the line evoking a stock market chart. Breen says she spent hours exploring the “plackets”—thin ribbons of fabric on a garment where buttons are fastened—that make up the work. She watched videos of placket production and learned that even in factories where machines do most of the work, actual people are responsible for feeding fabric through the device.

“I played with those plackets in so many different ways and in so many different colors and arrangements,” Breen says. Finally, a connection started to emerge, as she recognized that the color palette of white and blue stripes, light blues and grays, evoked the muted tones of corporate attire. “I was like, Oh my God, it makes sense. The people who wear these shirts are making decisions that impact the working conditions of the people who make them,” she says. “Seeing the plackets creating a graph of the ups and downs of the stock market . . . the irony of it really hit me.”

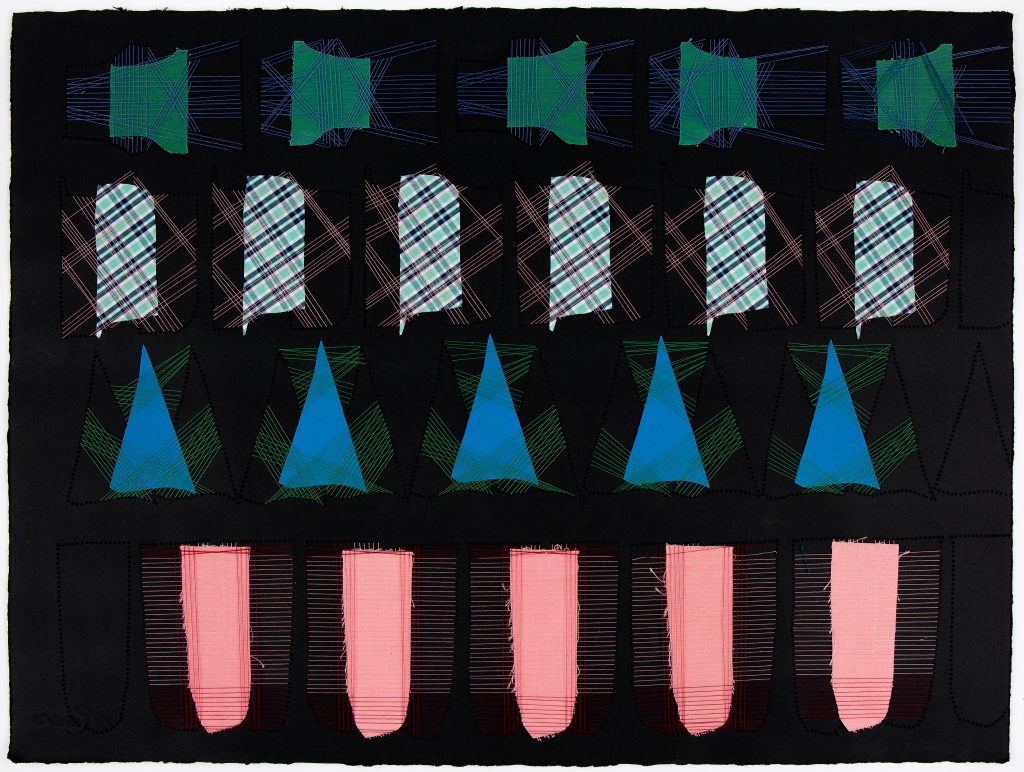

This work appeared alongside Piecework, an assemblage of shirtsleeves, and Collared, a wall hanging of rows of starched, colorful shirt collars, in the first room of The Labor We Wear, Breen’s recent solo exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), which was on display from July to November 2020. The show took aim at the garment industry, linking the labor of creating clothes—often done by women working in poor conditions—to the choices Americans make as consumers. Crisp and organized, the wall pieces felt rhythmic and symmetrical; you could almost hear the hum of the factory as you walked through the room. Breen says she wanted to remind viewers how clothes are made, to ask them to actually imagine the people who produce them. “I think a lot of Americans are pretty removed from assembly lines,” Breen says, especially as “a lot of factory work doesn’t happen in the United States anymore.”

As Breen arranged the pieces of clothing in various patterns, she encountered a challenge: Some of her designs were too pretty, which she felt dampened her message. “You can make all kinds of flowery designs with a sleeve,” she says. “But then all of a sudden, they become not sleeves. They become something else. I didn’t want that to happen.” The work in the show flirted with a transcendence of its material, without ever allowing the viewer to forget its original form. Collared in particular nearly recalled a flock of birds preparing for flight, but the strict, gridded arrangement kept the collars earthbound.

Shroud, the central piece in The Labor We Wear, was previously shown in 2018 at Carlton College’s Perlman Teaching Museum in Northfield, Minnesota, for an exhibition called The Price of Our Clothes. The piece consists of 1,280 white garments hung from the ceiling. The ghostly collection of hanging clothes represents the casualties of two major tragedies that happened nearly a century apart: the deaths of 1,134 Bangladeshi garment workers in the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in Dhaka, and the deaths of 146 garment workers—mostly young immigrant women—in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Manhattan. The mass of white cloth takes the form of a white burial shroud, used in both Muslim and Jewish burial rituals; most of the victims of the Bangladeshi disaster were Muslim, while the majority of those who died at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory were Jewish. “This commonality was part of what inspired Shroud,” Breen says. At the Perlman Museum, Shroud appeared alongside other artworks; at the Mia, the work had its own room, and its isolation emphasized its haunting, meditative quality. Walking beneath the dangling shirts felt like traveling within a ritual site of remembrance.

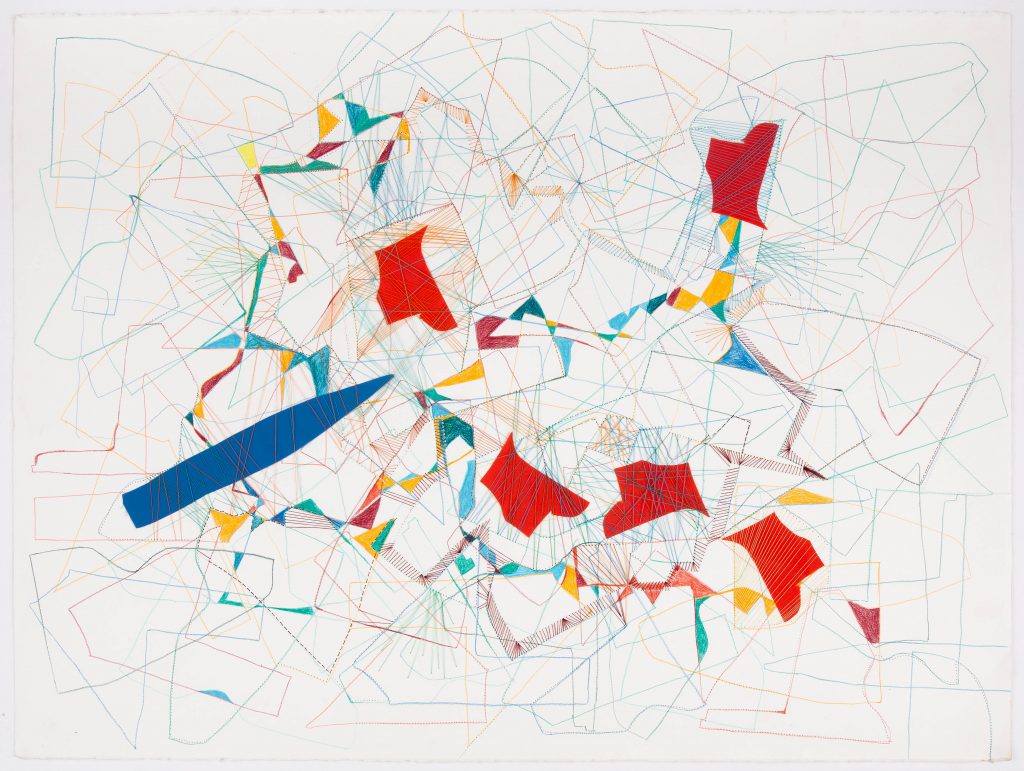

While doing research for the body of work that resulted in the show in Northfield, Breen and Alison Morse, who wrote poetry for the exhibition, traveled to Bangladesh and interviewed garment workers there, including survivors of the Rana Plaza factory collapse. “The public does not see the garment industry and the supply chain it depends on, because we’ve been taught not to see it, not to think about it, not to wonder where our clothes come from beyond the store,” Breen says. “My work seeks to make transparent the very opaque and complex system by which our clothes arrive in our closets.” This trip also inspired a new body of works on paper, currently on view at SooVAC Gallery in Minneapolis, in which scraps of garments Breen collected while in Bangladesh map out abstracted supply chains. While Breen’s other work on the garment industry ushers the viewer into the factory floor, these pieces connect the work of sewing to the transnational networks that deliver the products of this labor, with vibrantly colored stitching tracing the pathways of our complicity.

On April 24th, 2013, more than a thousand Bangladeshi garment workers were forced to enter the Rana Plaza or lose their jobs, despite obvious cracks in the eight-story structure. As they began work that day, the building collapsed on them.

In 1909, tens of thousands of Yiddish-speaking immigrants working in New York shirtwaist factories, most of them young women, went on strike. This action, dubbed the Uprising of the 20,000, was the largest strike to date by American women workers.

Breen identifies as both an artist and an organizer, and it was important to her that the recent exhibition at Mia also be an opportunity to connect the artwork to embodied action. Before the coronavirus pandemic forced the museum to close, Breen had intended to convene sewing circles in the exhibition space on the anniversaries of both the Rana Plaza factory collapse and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, in which participants could sit and stitch as an act of remembrance and solidarity. As an alternative, Mia hosted an online artist talk, featuring Breen in conversation with photographer and activist Taslima Ahkter, a coordinator of the activist organization Bangladesh Garment Workers Solidarity. The talk was publicized along with a flyer detailing ways to fight unjust labor practices in the fashion industry and declaring: “Collective action is the answer.” For Breen, her art is just one path toward asking the right questions.

Sheila Regan is a Minneapolis-based writer whose byline has appeared in The Washington Post, Hyperallergic, BOMB, and Artforum, as well as Minnesota Monthly, Midwest Home, and The Star Tribune.