Making History, Blintzes, and Trouble

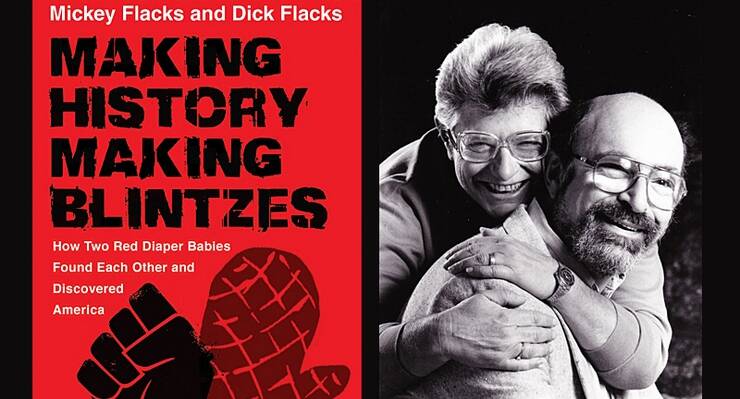

Longtime leftist activists Dick and Mickey Flacks reflect on their lives, their work, and their new memoir.

One would be hard-pressed to find important moments of the last 50 years of American progressive work that did not in some way involve Dick and Mickey Flacks. Fortunately for anyone interested in the history and future of the American left, the longtime activists and scholars have released a husband-and-wife double memoir, Making History / Making Blintzes: How Two Red Diaper Babies Found Each Other and Discovered America.

The memoir, available here at our Pushcart, begins decades before the lives of the authors, contextualizing their lives and their work in the Jewish leftist lineage they both share. The book covers the secular Jewish leftist world in which they were raised, their romance, the vital roles they played in building the New Left, the infamous attempt on Dick’s life, and the many years of vital activism from their move to Santa Barbara until today. It is a warm chronology of two principled lives lived fully and well. Dick and Mickey spoke to Jewish Currents about their lives, their work, and their new memoir. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jacob Plitman: What was writing this book like? A double memoir is a little unusual, no?

Dick Flacks: Writing this book together was easier than you might think. Really our whole lives have balanced political engagement and personal life and family. So a book that focused on those things wasn’t so hard. This book was like the rest of our lives together; on matters of importance, no disagreement. On small matters, vigorous disagreement.

Mickey Flacks: We wanted two different fonts for our separate sections, but the publisher wouldn’t let us.

The book is partly an attempt to set the record straight on our community’s history. I don’t want to name names but a lot of people haven’t done a good job describing growing up in a red Jewish family.

DF: Too much of the story of the many Communist Jewish families has been told by renegades of that time, people who swung from our community to the far right for a variety of reasons. And there was no monolithic experience. My upbringing in a leftist household actually made me a critic of the Communist Party and pushed me to seek out what would later be called the New Left. A lot of the point of the book is to share lessons we have learned together through our organizing.

JP: Your shared secular Jewish experience plays a huge role in your memoir. I’m one of the many millennial Jews who is almost completely secular, but who did not grow up in any institution that explicitly considered itself that. Can you say more about why discussing your secular Jewish experiences was so important?

MF: For a secular Jewish child, learning about your tradition is essential. Many people don’t know that the 20th anniversary of the secular leftist organization, the United Jewish People’s Order, was held in Madison Square Garden. There were a lot of people there. So, we were odd but big. And secularity at that time didn’t just mean “anti-religious.” We could understand the religious Jews’ ideology, even though we disagreed with it. Because we also had a system of beliefs that explained the world to us; we would meet together, even as kids, and discuss and learn what we called the “laws of social development.” We were historical materialists.

DF: Many people might not know that the secular world was composed of camps, clubs—we had different tendencies and practices. And secularity wasn’t just left wing. Zionism was generally secular too.

JP: Well this is part of why I think some wonder, if Judaism, secular or otherwise, isn’t inherently part of our political struggle—that is to say, if it isn’t inherently left wing—then what’s the purpose of salvaging it?

MF: This is an old debate. This argument was held between the socialists and the communist Jews of our and our parents’ generations. For leftists there’s a notion of an international proletariat or something that everyone has to be a part of, so it’s essential that we find common ground. The largest group in the Communist Party besides Jews were Finns. We were both disproportionately leftists. Our cultures were a way to talk to people. Everyone comes from somewhere. We don’t get set in the Earth simply as brothers and sisters, so you can’t ignore if people think of themselves as Jewish.

DF: It’s a difficult question. Is there a need for people to feel connected to collective identity? And national identity in this country, American identity, is pretty hollow, it’s inadequate. Because this is a multicultural place. In the 60s, we talked to Jewish people in Santa Barbara who said, “We don’t need to be Jewish, we have the counterculture. We’re creating our own culture.” And in the early 70s that seemed perhaps possible. But that hasn’t continued to exist, it wasn’t a sustainable framework for identity. And yet somehow religious and ethnic connections remained important to people. That’s why it’s worth developing that connection. Another reason is that developing that connection allows you to engage with the Jewish political world. If we leave, then what? We abandon our community to the Sheldon Adelsons. And that’s bad for the entire world.

JP: What else should young organizers take from this book?

DF: Build alliances not just about security, but about politics. Security isn’t the way we’re going to unite. I was almost killed for my politics. And the guy who did it is likely still out there somewhere. Mickey and I weren’t going to build our lives around anxious security. It may be kind of weird and irrational but we decided we weren’t going to expend a lot of our energy on what happened. There’s much too much focus on people feeling safe.

MF: A way of protecting yourself is not to dwell on it.

DF: I may grow to regret this but I don’t think the Squirrel Hill shooter is part of a new epidemic. I mean look at the black community, they’ve been bombed for decades and longer, and I don’t see them saying we have to arm people in churches. And look at [Norwegian mass murderer] Anders Breivik. Breivik hated a Pete Seeger song called “My Rainbow Race.” It was being sung in schools in Norway. A few weeks after the massacre, thousands of people gathered to sing that song in Norwegian. That’s the way to counter this kind of violence.

We also want young organizers to read the story about us and the Students for a Democratic Society—we were married and got to have children in the midst of all this turmoil. So maybe the more important part is the 50 years after that. Living life and being engaged at the same time.

Some people measure the left by the strength of left-wing parties and organizations. The left is a much broader movement, phenomenon, current, tradition than any particular sort of organization. And in fact those orgs have been deleterious. That may be controversial. Some might think, unless it’s explicitly socialist, or it pays tribute to Marx, or is a party, it’s not the left. We’re not going to get social change if “conversion” is what we want. We can’t expect everyone to be converted to an ardent leftist. Today’s left encompasses different mindsets and that’s good. In the old left, people had to break with the party in order to think differently.

MF: It’s also important for young activists to understand the variety of experiences that made up the Jewish left. For me, I grew up in economic uncertainty. [Regarding Dick’s work] I didn’t care how little the money was but it had to come in weekly. My mother was a genius at giving the appearance of a lower middle-class life on close to welfare income. I wanted a decent job. And I mistrusted what I used to call “pie cards,” a Wobbly term for people whose profession was the movement. That included labor unionists, movement organizations. I didn’t mistrust them really, but I didn’t feel a bond with them. They were living off my parents’ meager incomes, who religiously gave to these organizations, and some of the professionals had a higher-class life than my parents did.

JP: Mickey, could you speak to the role of Yiddish in building the movement you’re describing?

MF: For me, it was a home language, a kitchen language. It was the revolutionaries who realized you had to know Yiddish to speak to the workers. It was a kind of utilitarian thing. But it became a thing unto itself, and Yiddishism was born. Yiddish is both a way to connect with a leftist history and a thing unto itself, like our culture in general. Enough of you have to learn enough to carry it on.

Jacob Plitman was the publisher of Jewish Currents from 2017-2022, during which time he stewarded the relaunch of the magazine.