LAST SATURDAY NIGHT at one in the morning I walked into a performance called “foreignfire presents: Thresh” at the 14th Street Y. I was in the beginning stages of regret at having stayed so late to participate in an immersive piece of performance art by a new acquaintance, the Israeli sound artist David Katz, who founded the collective foreignfire. I’d met Katz the night before, and had been genuinely compelled by the way he described the relationship between his art-making and the traditional liturgy he engages with in his role as music director for a Reconstructionist synagogue in San Francisco. But by that point in the night I was tired, and felt burdened, too, by the weight of the Jewish content I’d learned, chanted, heard, and consumed under fluorescent light in the Y’s “dusk to dawn” Shavuot program.

But I’m glad I stayed, because “Thresh” turned out to be the best part of the night, and my only meaningful (and unexpected) engagement with the Book of Ruth, Shavuot’s primary text. I fear I’ll spoil the experience for future participants by describing it here, but I also can’t stop thinking about the way Katz facilitated an experience in which meaning was layered in concrete and conceptual terms through the spontaneous orchestration of bodies in space.

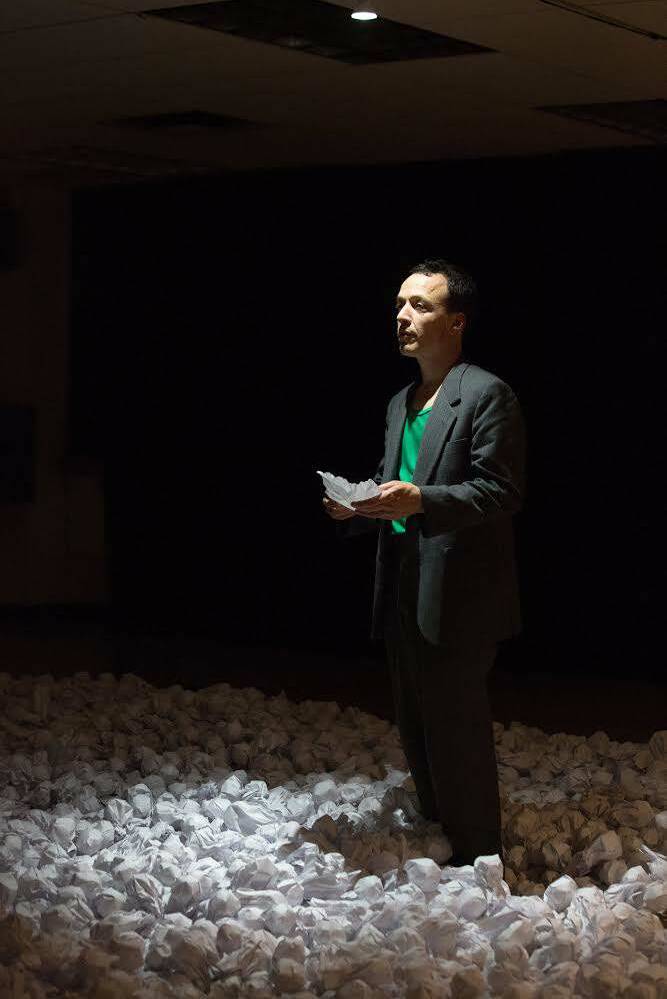

I waited with a small group of strangers for the performance to start, and when the door opened, we walked into a room that was dimly lit. Covering most of the floor were piles of crumpled balls of paper, rolled in a pleasing shape, not unlike a paper balloon. As we entered the room, Katz was kicking his way through the piles like a child in a field of dry autumn leaves. It was irresistibly appealing, and without prompting, we joined him. When Katz reached down and uncrumpled one of the sheets to read it, we did it too, and discovered that each balloon had text on its interior, and each text was a kind of directive. (Throughout the entire piece, which lasted about an hour and into which participants entered and left at will, there were never any introductory instructions given besides the text directives themselves.)

The first sheet I opened said simply, don’t go home hungry, which delighted and disarmed me. I re-formed the paper into a ball, tossed it back into the pile, and chose another one, which said something like sit at the feet of someone who is standing and follow their lead. So I found someone who was standing and brushed the piles of paper away to sit at his feet; about a minute later he kneeled down beside me and looked into my eyes and held that eye contact silently for half a minute or so before reaching over and kissing my forehead. The moment was charged with intimacy and ambiguity. And so it went: there were directives that involved vocalizations, including one that asked me to take someone’s hand and walk counter-clockwise around a standing person 10 times, whistling or singing a blackbird’s song. This I happened to do with Katz, whose bird-call whistles were so accurate and lively that most of the room seemed to turn almost imperceptibly to listen. Throughout the performance, participants were consistently engaged in the directives, or waiting, or watching, all of which Katz calls “threshing” in the texts (as in the directive keep threshing).

At one point, I followed the directive to kneel down and put my hands on someone’s shoulders and whisper into his ear, You are mine. Your dreams are my dreams, your heart is my heart, your thoughts are my thoughts, your blood is my blood. At the time I found the words moving and unexpected, and only connected later that it’s a kind of translation and inversion of the lines that Ruth declares to her mother-in-law, Naomi: For wherever you go, I will go. Wherever you lodge, I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die; and there will I be buried…

Other notes asked me to walk, howling, from the center of the threshing floor to the outer edges, or to sing someone a song from my childhood, or to scream as loudly as I could. Sometimes the texts just said things like keep looking until you find it, or don’t leave. Each time I discovered a new directive, even these simple but existential ones, it was a quiet thrill. I felt increasingly under the spell of an intense game you can lose yourself in precisely because you know that—even if it’s scary—ultimately you’re safe (it turns out it’s a little terrifying to make strange and sudden loud noises in a quiet room full of strangers).

One directive said come closer, another come closer until you eat it, which I decided meant to kind of face-plant in the paper thresh, to lie there for a while just listening to all the motion around me. I could hear a steady shuffle of the paper being walked through, a crumpling crunchy orchestration that I imagine is meant to recall the sound of actual threshing: the act of separating grain from chaff, in the ancient world achieved by a beast of burden crushing sheaves with its hooves, led in a circle. This practice took place on what’s called a threshing floor, which I know from the story of Ruth as the site of her offering herself to Boaz, if somewhat ambiguously, and if “offering” is the right word in terms of her agency in a story that lays bare the difficulties and tragedies of being a single woman and a stranger in a foreign land.

And so I found myself lying on the floor and thinking about threshing, which is an act of force that also requires delicateness, like art-making, like prayer, like love. As people came in and out of the room it became obvious who was timid and who bold, which pushed me to be braver in the contained space that functioned like a kind of sideways mirror.

It ended as subtly as it had begun, with only a few people left in the room after two am. I left for a few moments to collect my thoughts. When I returned to say thank you to Katz, I saw him standing in the room looking out over the masses of paper. The air was still quiet, still charged, though the pressure of the performance was broken.

Maia Ipp was one of the four editors who relaunched Jewish Currents in 2018. She is a writer of fiction and cultural criticism and the artistic director of the New Jewish Culture Fellowship. In 2020–21 she was a creative writing teaching fellow at Columbia University, where she also held a De Alba fiction fellowship.