Grave Disturbances

Anna Burns’s Milkman bears witness to the private pain subsumed in political violence.

Discussed in this essay: Milkman, by Anna Burns. Graywolf Press, 2018. 360 pages.

IN “BAD VIBES,” an essay published in The New Inquiry in 2015, Amanda Mae Yee recounts an experience of being stalked in north London. Six times over the course of two months, she noticed the presence of a strange man in a black hat and overcoat—often at night, or in the grocery store; once, on her usual bus route. While he made no attempt to speak to her, twice he walked past “so close to [her] physical person” that they nearly touched. So-called objective reality failed to provide an explanation for his hovering or for the visceral dread overwhelming her. It also made the situation difficult to name. What do you call a threat so ambient it might as well be air? All the same, she writes, “I kept seeing him, and I could not ignore or rationalize the sheer force of somatic experience that accompanied the incidents. My body was signaling that something was very wrong.”

In Anna Burns’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel Milkman, this phenomenon is given a name: “anti-orgasm.” Middle sister, the novel’s unnamed narrator, describes it this way:

[T]he base of my spine had seemed to move. It had moved. Not a normal moving as in forward bends, backward bends, sideways and twistings. This had been a movement unnatural, an omen of warning, originating in the coccyx, with its vibration then setting off ripples—ugly, rapid, threatening ripples—travelling into my buttocks, gathering speed into my hamstrings from where, inside a moment, they sped to the dark recesses behind my knees and disappeared.

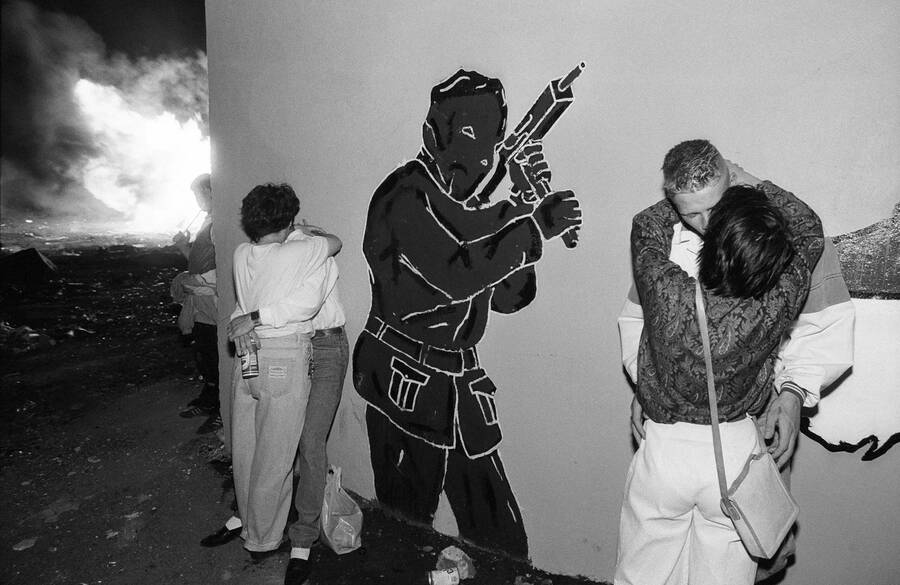

The source of these ripples is the titular Milkman, who is no milkman at all, but rather a middle-aged paramilitary “renouncer-of-the-state,” which is to say a member of the IRA, in the embattled Northern Irish city where he and middle sister both live. It is the late 1970s, and the Troubles have been going on long enough that many have taken to calling them “the sorrows” instead. Before Milkman intrudes, middle sister’s life has a predictable shape, if one circumscribed by sectarian conflict. Every morning, she catches the same bus to her job downtown—or at least, “every morning when it wasn’t being hijacked.” In the evenings, she walks home with a novel in hand and goes for runs in the local parks and reservoirs, where, every so often, the hidden cameras of state forces “click” to document suspected renouncers and their associates. Her mother harangues her for remaining unattached at 18, when she should be settling down with a husband and having “right-religion babies.” A few nights a week, she meets up with her “almost one year maybe-boyfriend,” whose existence she hides from her family.

Slipped in among all this is what might, in another novel, constitute an unbearable amount of whimsy: a trio of precocious “wee sisters” whose interests range from “the whirlwinds of the Faeroe Islands” to “the diatonic scale, prefectures in China, the non-local universe, [and] the theories and facts of material science”; a middle-aged couple who abscond from their home and six children in order to become world champion ballroom dancers. But these twee flourishes are constantly undercut by violence, which is relayed, if not dispassionately, then nonetheless as a matter of course. Heads are blown off and never recovered; a toddler falls to his death from a window while his mother lies insensate over the murder of her grown sons. The graveyard where the renouncers are buried is referred to simply as “the usual place.” In one particularly gruesome episode, middle sister recalls the time state soldiers slit the throat of every dog in the neighborhood before piling them all together in a “slimy, pelty mass.”

It is within this context of grave violence made mundane that Milkman first pulls his small white van up beside middle sister as she walks along reading Ivanhoe. He offers her a ride; she demurs. Later, he appears like a ghost beside her on a run through the parks and reservoirs. Here, middle sister realizes that his interest is prurient: “I had a feeling . . . an intuition, a sense of repugnance . . . but I did not know intuition and repugnance counted.” The fact is that they don’t, at least not for much. Milkman wields the silent authority conferred onto him by his gender, his age, and his position near the top of the renouncer hierarchy. Soon his van is idling outside her weekly French classes, and he’s making what sound like veiled threats of a car bombing against her maybe-boyfriend.

The creeping horror of this situation does not derive only from the familiar specter of an older man in pursuit of a much younger woman. (Burns does not linger much over their age difference, except to have middle sister derisively refer to Milkman as “that man who is two hundred years old.”) What haunts middle sister most is the total isolation of her plight. She can’t report Milkman’s behavior to the militias who keep order in the neighborhood—he’s one of their own. Taking the matter to the actual police, the state police, would be tantamount to treason against her own community. And even if she were able to make a report, it’s unclear what it would contain: the indefinite nature of the stalking, of even the threats, places them in a category that simply does not exist in middle sister’s world, where “everything had to be physical . . . in order to be comprehensible,” especially when “huge things, physical, noisy things, were most certainly, on a daily basis, an hourly basis, on a television newsround-by-newsround basis, going on.” In a war zone, only bodies are permitted to speak.

This point is crystallized when a handful of burgeoning feminists in the neighborhood start a consciousness-raising group, only to be quickly dismissed as “the women with the issues.” It doesn’t take long for the broader community’s disdain and bafflement at these women organizing for their own interests to curdle into something worse. That the women might have broad political aims of their own, unbounded by the question of the right or wrong religion, but equally oppositional to the state, does not register as a possibility to the renouncers, who threaten them with violence when it gets out that they invited an English facilitator to their meetings. Though middle sister admits that “in some measure regarding [this group’s] issues I might be in agreement,” the demands of loyalty and political conformity keep her separated from the only people who might supply a language for what Milkman is inflicting on her.

As Milkman’s predations intensify, Burns’s compulsively maximalist prose careens like the speech of someone as sure of themselves as they are unsure of what’s about to come out of their mouth. In their contortions, repetitions, and evasions, her sentences come to resemble the avoidant behaviors of middle sister herself, whose coping strategies of reading-while-walking, shunning 20th century politics for the 19th century novel, and rebuffing all questions about her personal life with a stoic “I don’t know” have unwittingly landed her on the list of the community’s dreaded “beyond-the-pales.”

Middle sister’s sole confidant, her oldest friend from primary school, explains that her stoicism and her habit of ambulatory, involved reading are “disturbing” and “deviant” and “[n]ot public-spirited.” Moreover, such behavior calls attention to itself. “[W]hy—” her friend asks her, “with enemies at the door, with the community under siege, with us all having to pull together—would anyone want to call attention to themselves here?” This is news to middle sister—that keeping her head down has attracted more notice than Halloween masks, balaclavas, or machine guns ever could. She agrees to drop the reading but not to begin answering those personal questions, the ones about Milkman: “I didn’t want to. Still I didn’t want to. This was my one bit of power in this disempowering world.” Against both Milkman and the neighborhood gossips, refusal is her last recourse. “Saying nothing is a preliminary method of no,” Anne Boyer writes of such calculated silence in A Handbook of Disappointed Fate. “To practice unspeaking is to practice being unbending.”

But it’s hard not to bend when your body is struggling to hold itself upright. Despite its intangible nature, Milkman’s stalking begins to take a physical toll. Paranoia keeps middle sister up at night; this leads to drowsiness, dullness, phantom pains in her legs, which forces her to stop running altogether. Soon breathing becomes a problem, then balance. The shuddering revulsion she feels toward Milkman finds its way into her own maybe-relationship like a malignancy; the loss of her autonomy seems to discount the possibility of any pleasure at all. Worn down, middle sister eventually gives in and, knees buckling, accepts a ride from Milkman. “It was that there was no more alternative,” she thinks. “I was Milkman’s fait accompli all along.”

But if Milkman’s triumph over her will is a fait accompli, then so is his eventual death—the reader knows it’s coming from the novel’s first line. Speaking to the Financial Times, Burns remarked that “in my book it’s sexually dangerous to be female, but I think it’s much more fatally dangerous to be male.” This isn’t a value judgment; in Milkman, it’s taken for granted that living doesn’t always feel like being alive. Middle sister’s late father suffered from “coffin-upon-coffin, catacomb-upon-catacomb, skeletons-upon-skulls-upon-bones crawling along the ground to the grave type depressions.” Before Milkman is killed, middle sister herself starts to resemble the walking dead from the effort of so much withholding: “My head . . . began itself to doubt I was even there.”

There is a sense throughout the novel, which middle sister intimates she is narrating from some point in the future, that the paralyzing bewilderment she once felt in the face of Milkman’s actions has since passed into a kind of zen comprehension—now that we are living in what she calls “the era of psychological enlightenment.” The line may be tongue-in-cheek, but it’s nonetheless difficult for this reader to entertain the linear narrative of progress it implies. Some 40 years on from the history dramatized in Milkman, in settings much less obviously politically extreme, women still struggle to make their harassment understood (being believed is another matter entirely). However tiresome its overapplication may be, the explosion of the term “gaslighting” over the last few years speaks to a lingering hunger to taxonomize these psychological injuries, so that they might be recognized as legitimate. In “Bad Vibes,” Yee writes, “The political imaginary we exist in holds the most vulnerable as most subject to doubt and figures their bodies rather than their words as sites of truth.” The growing understanding that physical assault is often preceded or accompanied by less tangible forms of abuse has yet to significantly transform this hierarchy.

In Milkman, Burns’s canniest trick might be reversing the logic that so alienates her narrator, whose private, indefinite pain is subsumed by the public violence of the Troubles. If middle sister’s habit of eschewing proper nouns for a more expedient shorthand—“us” and “them,” “over the border” and “over the water”—positions the reader as an insider to the conflict, it also shrouds what she merely calls “the political problems” in vagueness. The setting largely fails to overwhelm the immediacy, or the anxiety, of middle sister’s disintegration, her struggle to evade the Milkman. This smaller story is, in the end, the one to which we bear witness.

Jess Bergman is an editor at The Baffler and a contributing writer for Jewish Currents.