The Local Lulav

In creating our diasporic lulavs, we asked ourselves what a radical, ethical practice of Sukkot looks like in our various homes.

WE ARE A GROUP of Jews from across Turtle Island (what is currently known as the United States) who came together to create diasporic lulavim, made from plants that grow in the places where we live, and that have deep meaning to us in the places we call home. In creating our lulavim, we asked ourselves what a radical, ethical practice of Sukkot looks like in our various homes. Last year, we explored this question in The Book of Lulav, a zine that’s full of reflections, tips, and resources about creating your own diasporic lulav.

We are connected and drawn to the rituals practiced by many of our ancestors and our families, and seek to find ways to create these rituals in a way that is relevant to our lives and our values. Our lulavs—both the ritual object and the ritual acts—are situated in diaspora, and explicitly reject the colonization of Palestine and the mandate to use the “four kinds” (“arbah minim”) of plants associated with the biblical Land of Israel. Yet, as people with no American Indian ancestry, we recognize that all of our lulavs are still created on colonized lands. We must wrestle with settler-colonialism, not run from it or ignore it. We aim our diasporic longings towards the process of decolonization, materially and otherwise. We are motivated also by an anti-capitalist/anti-consumerist ethic of not purchasing expensive ritual items produced by a very small number of private companies, and by an environmentalist ethic of not shipping lulavim over long distances.

The “four kinds” (arbah minim) of the traditional lulav are:

- Lulav: branches of palm trees

- Hadass/myrtle: boughs of leafy/braided trees

- Arvah: willows of the brook

- Etrog/citron: fruit of beautiful trees

In creating our lulavim, we followed several different frameworks from Jewish textual traditions, adapting them to the plants that felt right to us. The North Carolina Piedmont lulav includes plants for each of the four kinds based on their relationship to the senses (i.e., smell and taste, taste and no smell, smell and no taste, neither smell nor taste). The California lulav includes plants with similar relationships to their ecosystems as the traditional plants. The Detroit lulav uses plants that live near water and enliven the senses, and which also visually match the traditional plants. The Ann Arbor lulav is made of plants that connect to a personal idea of home. In the zine, we also explore other traditional frameworks, where each plant represents a part of the body (spine, lips, eyes, and heart), one of the matriarchs and patriarchs, or one letter in the four-letter name of the divine.

North Carolina Piedmont: The homelands of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation.

- Tulip Poplar (Lulav): Taste and no smell. These branches from a strong and significant fruiting plant hold a prayer and a demand: No more strange fruit. A commitment to transform the structures and trauma of anti-black violence in the landscape of the South. The Poplar also offers the promise of sweetness, and abundant nectar for the bees.

- Pine (Hadass): Smell and no taste. Breathing its beautiful scent offers an appreciation for sensuality and the senses.

- Willow (Arvah): Neither smell nor taste. A prayer for clean water for all and a commitment to care for this planet that is our home.

- Apple (Etrog): Smell and taste. This delicious, sweet-smelling fruit is grown in the mountains and shaped like a heart. Apples are both part of the history of colonization here and have have been cultivated by indigenous people for generations, so this serves to recognize that we are still on colonized land.

- Noah Rubin-Blose

Detroit, Michigan: The stewards of this land are the Haudenosauneega Confederacy, Anishinabek, Miami, Peoria, Odawa, and Potawatomi.

It was important to me to use plants that grew in or near water to reflect the ancient water drawing ritual, Simchat Beit Hashoavah, done during Sukkot. I had to make two adjustments to my lulav this year, most likely due to climate change, replacing sumac with goldenrod and black walnut with an apple. Both plants have come and gone already this year, though in years past, they were still strong into October.

- Cattail (Lulav): Cattails are the epitome of water-dwelling plants; we keep them in hopes for the right amount of rain for next season’s crops.

- Goldenrod (Hadass): Goldenrod lives in damp, swampy areas as well. It’s familiar and native.

- Willow (Arvah): Another wetland tree and part of the traditional “arbah minim,” but in a native, carbon-neutral form.

- Apple (Etrog): My two year old picked this apple at a local orchard. I keep it as a reminder of joy and innocence.

- Rakia Sky Brown

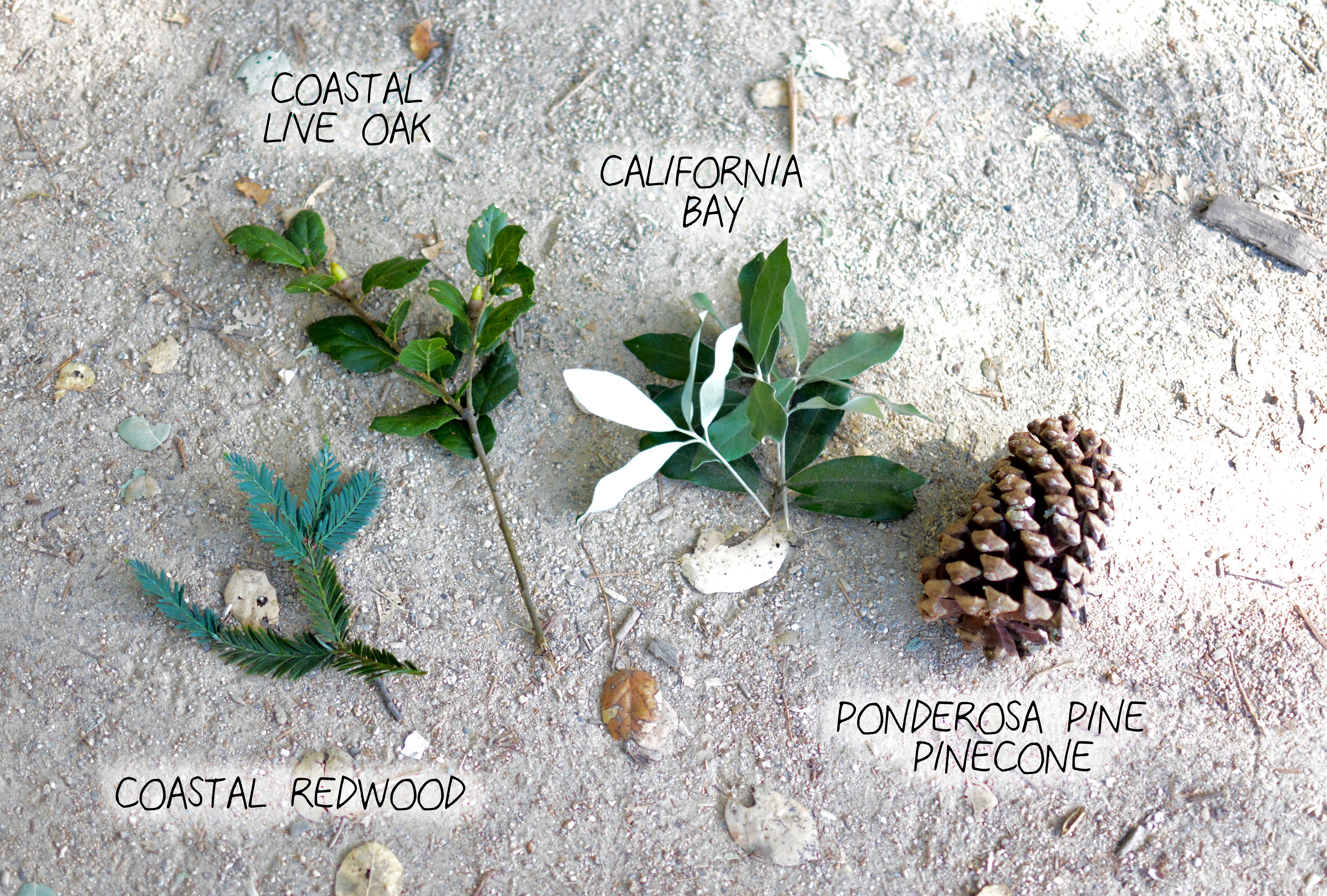

The East Bay, California: Chochenyo & Karkin Ohlone territory.

- Coast live oak (Lulav): Native California oaks can easily grow to be 500 years old. They don’t like growing too close to bodies of water and prefer to tap deep roots. Acorns of various oak species are the key food source for dozens of native animals and were/are a crucial food source for California Indian nations including the Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone, on whose land I live.

- California bay (Hadass): California bay grows in the coastal mountain ranges to the west, often along rivers and creeks. It is fragrant and its leaves can be used as flavoring or for tea.

- Coastal redwood (Arvah): This stands in for the willow. Redwoods are fog drinkers, and get a lot of water directly through their leaves. They have remarkably shallow root systems for being some of the oldest and tallest trees in the world.

- Ponderosa Pine Pinecone (Etrog): Pinecones are fertile and filled with countless seeds, like an etrog, symbolizing fertility. Native creatures and fire both help open the cones and disperse the seeds, symbolizing rebirth from catastrophe.

- Gabi Kirk

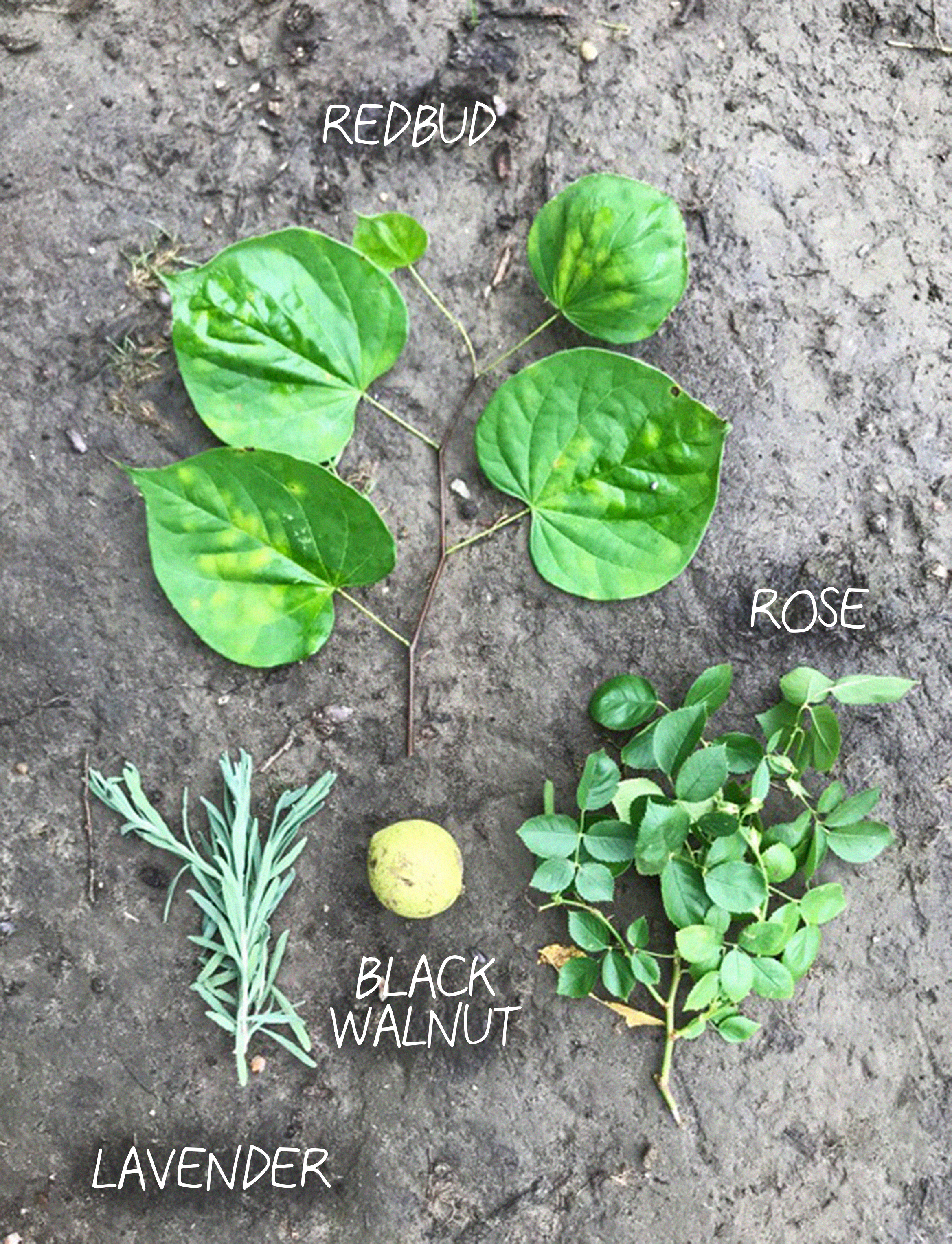

Ann Arbor, Michigan

I’ve moved a lot in the past year, so this Sukkot my lulav is all about connecting to plants in order to ground myself in what home means for me. At the same time, I acknowledge that the land I am learning to call home has been home to many indigenous populations, including the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi—the land that the University of Michigan was built on was taken from these tribes.

- Rose (Lulav): I harvested the rose from in front of the house where I live in Ann Arbor. It symbolizes the prickly and sweet nature of returning home.

- Lavender (Hadass): I harvested this lavender from my mom’s garden behind my childhood home in Metro Detroit. This is a place, and plant, that soothes me and that I’ve known my whole life.

- Redbud (Arvah): I harvested this branch from a tree by the Huron River. Swimming and mikvehing there is helping me feel connected to this area.

- Black walnut (Etrog): I learned about this fragrant plant on a Jewish farm in Connecticut, but it’s also found in Michigan; it’s become a personal symbol of reconnecting to the land, wherever I am.

- Miriam Saperstein

Rakia Sky Brown is an emerging Kohenet, farmer, ritualist, professor, and birth-death doula.

Noah Rubin-Blose is a trans Ashkenazi Jewish ritual-maker and organizer from Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Miriam Saperstein is a poet, zine-maker, and library science student in Detroit, Michigan. They were a 2020 New Voices/Jewish Currents fellow. Their work has also been featured in the lickety~split, ctrl+v, and Protocols.