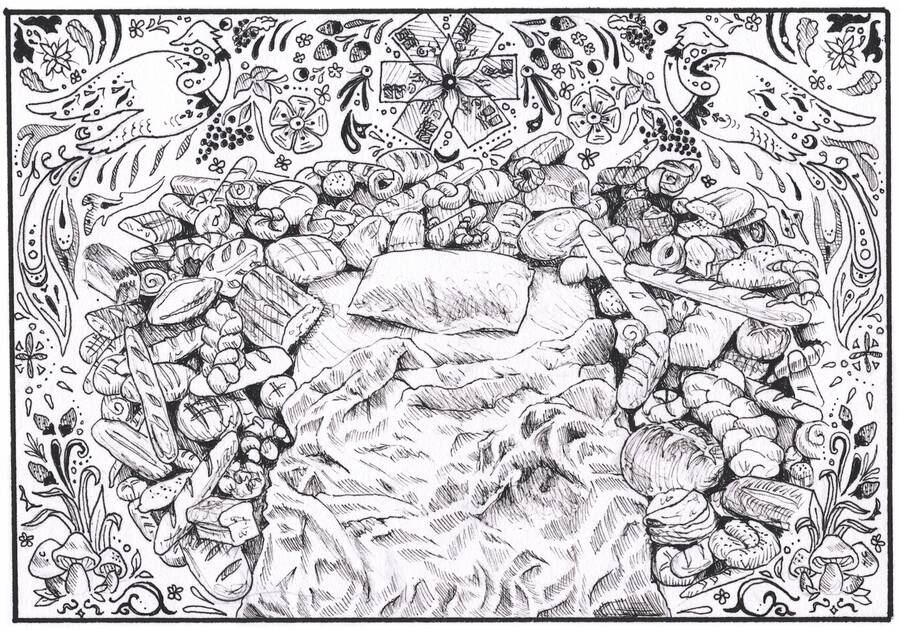

Bread

A new translation by Ellen Cassedy from the forthcoming collection On the Landing: Stories by Yenta Mash.

Yenta Mash (1922-2013) grew up in the region of south central Europe once known as Bessarabia, now Moldova. In 1941, at the age of 19, she was deported along with her parents and other “bourgeois elements” to Siberia, where she endured six years of hard labor, privation, and hunger. After her release from the labor camp in 1947, Mash settled in Chişinău (Kishinev in Yiddish), which had become the capital of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1977, she moved to Israel, and there, in her 50s, she began to write. She published four volumes of stories and essays in Yiddish and received numerous prizes. Her work won praise both for its literary style and for its insights into little-recorded aspects of Jewish experience in the 20th and 21st century.

Mash’s work has not yet been available in English, which is one reason we’re excited about Ellen Cassedy’s elegant translations in On the Landing: Stories by Yenta Mash (Northern Illinois University Press, 2018). The story that follows, “Bread” (“Broyt”), appeared originally in the collection Tif in der tayge (Deep in the Taiga) (Tel Aviv: Farlag Yisroel Bukh, 1990). Like many of Mash’s stories, “Bread” is what now might be called auto-fiction. It offers an unflinching statement on “the spoiled, empty-headed children of Israel” Mash encountered in her later life, and the sacrifices made especially by women in wartime: “No one mentions it—that’s the way it is with mothers.”

– The Editors

EVERY DAY at the break of dawn they arrive, the man and his horse—or should I say the horse and his man? The horse is so big, with sturdy hips rippling under a shining chestnut hide, that it could well be the boss of the little Yemeni man with his wispy beard and long side curls.

The horse apparently needs no whip; it goes straight to the rubbish bins and stops as if to say, “Here we are, now do your job.” The man doesn’t have to be told twice. He jumps down from the cart and gets to work. First he picks out a good-sized roll and offers it to his esteemed partner. The horse accepts the roll with dignity, sniffing all sides of it while reciting the hamotzi blessing in the language of horses, then chomps away with its big teeth while the man goes about expertly collecting and sorting, filling the row of cardboard boxes in the wagon: one with bread, one with challah, others with rolls, buns, pitas, even day-old home-baked pastries—all the leftovers that the spoiled, empty-headed Children of Israel think they’re too good for.

What does he do with the bread? It doesn’t matter, so long as he takes it away—away from the rubbish, away from the stray cats scrounging in the bins, away from all who might look with pity and sorrow on the tragedy of bread taking place daily in this country.

When the man’s work is done, he waits patiently for the horse to shake its head—a sign that it has finished the blessing for the close of its meal—before they move on to the next bin.

As I watch them leave, pictures appear before me, pictures engraved in my memory, pictures that will accompany me to the end of my days.

1943. The height of World War II. A howl of lamentation resounds from one end of Russia to the other. Death knocks ceaselessly at our doors, delivering brown envelopes with official stamps bringing news that a father or son has “fallen heroically on the battlefield in fulfillment of his duty to the Fatherland.” The bereaved wail to the heavens, split the skies with their cries, writhe in pain—and early the next morning they take their place in the ochered, the breadline. Bread—bread is holy! Bread waits for no man. Bread rhymes with dead. In those years, the last thing likely to appear before a person’s eyes as he takes his final breath is a slice of bread.

As soon as you get to the head of the line, you become nothing more than a pair of eyes. No power on earth can make you stop watching the woman’s hands as she checks your cards and weighs out your family’s share for the day—500 grams for workers, 200 for everyone else. The bread is sticky and heavy, a mixture of bran and potatoes, but you’re used to it, as if you’ve never eaten any other kind. All you care about is getting your portion. Every extra crumb kindles a spark of hope in your heart—a hope against hope.

Meanwhile, everyone is gathered around the table waiting for Mother, and when she arrives, it’s the same thing again: all eyes, big and small, are fixed on her hands as she divides the loaf. The crumbs that break off during the slicing of your portion belong to you, and you’re not embarrassed about scraping them up and putting them straight into your mouth so as not to lose them. You don’t worry that others will laugh or call you greedy, because everyone does the same thing. You hold the crumbs in your mouth for a long time, chewing and sucking, without taking your eyes off Mother’s hands as they continue slicing and dividing. No one moves until all the bread has been distributed. Only then do you swallow—not noticing, or at least pretending not to notice, that the very last portion, the one Mother has left for herself, is smaller than anyone else’s. No one mentions it—that’s the way it is with mothers. Since the adults are in a hurry to get to work, the soup is brought straight to the table. Spirits rise, especially when a chunk of beet or potato shows up along with the millet. Fragrant steam rises from the earthen bowls, and wooden spoons dance before your eyes. You slurp up the soup, the hotter the better, scalding your tongue and smacking your lips.

You don’t eat the bread yet. You eat the soup first while the bread is toasting on the stove. Every piece is laid out just so, and you can turn any charred crust into roasted meat or pastry or whatever you wish—all you have to do is close your eyes and remember the old days back home.

You know you ought to divide your piece in two and save half for the evening meal, but it’s hard to resist temptation when you’re hungry. You pinch off a little piece, then a little more, and even more, until it’s gone. You sigh, but at the same time you pat your belly as if to say, “I’m full now—let God worry about tomorrow.” After an hour or two, though, the meager meal has disappeared as if it was never there, and you’re hungry again. You try to subdue the pangs with work or play, but the chunk of bread you should have saved sticks in your mind. If only you had it now, even a tiny piece! You berate yourself in the worst terms and solemnly swear that tomorrow . . . Yet when tomorrow comes you’re hungrier than ever, and once again you can’t hold out. You resign yourself to your fate and your “weak character.” Even a child knows that each of us receives our portion according to what is polozheno—officially allotted—which is like what we say in Hebrew, min hashamayim, ordained in Heaven. So you accept the verdict without complaining or crying or asking for more.

IN THOSE BITTER DAYS, we’d been scattered to the ends of the earth, exiled to Siberia for our own or our parents’ supposed transgressions. We were the lost tribe, the deportees. Once upon a time, we’d been lovely brides and schoolgirls, shielded from the slightest breath of wind. After two years of hard labor, it was hard to recognize us as those same young ladies. We spent all day in the forest dressed in rags, our trousers held up with twine, faces covered with masks against mosquitoes, buckets and shovels in our hands. Starving, exhausted, isolated from all human contact, we had the feeling that the Lord Himself had gotten lost somewhere up in the tall, dense crowns of the pine trees and completely abandoned us. It was left to God’s deputy, our nachalnik, to rule over us according to the law of the taiga, by force. He was fully prepared to rip our hearts out for the slightest infraction. Our hearts—as if he of all people had anything to do with our hearts. But if he took away our portion of bread . . . oh, then he could make us truly wretched—and have more for himself. So we had to throw the dog a bone, flatter him by addressing him by his full title, and rush to obey whatever order happened to cross his mind: to chop and carry his wood, light the fire in his stove, do his laundry, clean his room, scour his floor with sand until it shone. We did everything we could to soften him up, hoping that when he weighed the buckets of resin we’d worked so hard to collect he wouldn’t be too strict, and that when he measured the wood we’d sawed and chopped he’d overlook the pieces of bark we sneaked in here and there.

Besides bread, twice a day, morning and evening, the kitchen gave us soup made from the dregs of soaking barley-straw. The soup was hot and it stuck to our ribs, quieting our hunger for at least a short time. On top of that, we ate whatever we could find in the forest. Into the sacks hanging from our shoulders went mushrooms, kolba (wild garlic that was said to guard against scurvy), and above all, berries: currants, blackberries, lingonberries, wood sorrel, and others whose names I’ve forgotten, thank God. The berries were our manna, but with a difference. Rather than falling from the heavens, this manna had to be collected from swamps and marshes, and in order to find it you had to walk with your head down, eyes fixed on the ground. Alas, people often wandered deep into the forest, lost their way, and never returned. This is what happened to my mother, of blessed memory. On the twentieth of August, 1943, she went into the forest to gather berries, and she will remain in the taiga to the end of time. When I came home from work and realized what had happened, I screamed at the top of my lungs. Everyone from our district, led by our boss, headed into the woods to look for my mother. We carried lanterns, sticks, and a rifle. We yelled and banged and whistled and shot off the gun, listening for a response—all in vain. Late at night we returned empty-handed. Exhausted from weeping and shouting, I went into our little room. When I lay down on the bed we shared, I felt something under my head. I lifted the pillow and burst into tears. There, wrapped in a white handkerchief, was the crust of bread my mother had been saving for later.

Forty-three years have passed since then, and only now do I confess that I ate my mother’s bread that night. I soaked the crust with bitter tears and I devoured it.

NOW I LOOK out into the early morning and I wonder: my God, how many lives could be saved with the bread we throw away every day? I think of the moist white loaves of braided challah we have on Shabbos. We put them on the table in a place of honor, we cover them with a white embroidered cloth, we light the candles and we say a blessing over them . . . and the next day we toss those very challahs in the garbage. Why, I ask, why do we even bother to bless them?

Yenta Mash (1922-2013) won several awards for her largely autobiographical stories, which trace an arc from her beginnings in an Eastern Europe shtetl, to Siberian exile, to Soviet Moldova, and finally to Israel, where she was part of the Yiddish literary circle.

Ellen Cassedy is the author of the prize-winning We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust (University of Nebraska Press, 2012). She is also the translator of On the Landing: Stories by Yenta Mash and is the co-translator with Yermiyahu Ahron Taub of Oedipus in Brooklyn and Other Stories by Blume Lempel.