Ocasio-Cortez’s Jewish Heritage Isn’t About You

AOC’s announcement of Jewish heritage needs to be read in the context of Sephardic and Latin American history.

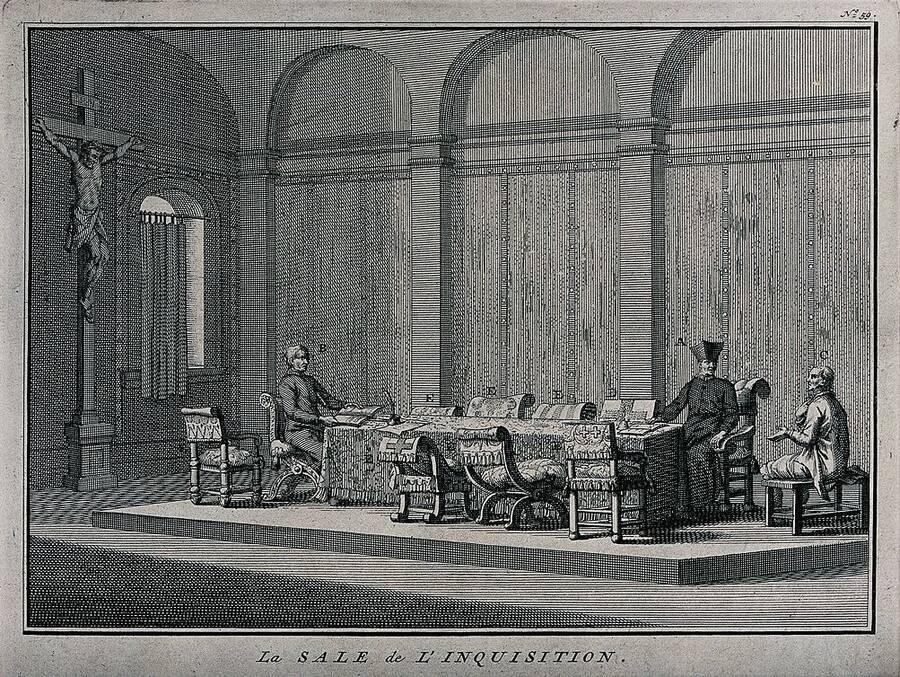

SHAUL MAGID’S recent essay in Jewish Currents started a nuanced conversation about the meaning of Democratic congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Jewish heritage. Magid convincingly begins and ends his argument with an important historical example of intercommunal Jewish gatekeeping from 16th century Safed, highlighting competing notions of Jewish authenticity amongst Jews—issues which have embroiled Ocasio-Cortez’s declaration of Jewish heritage since she made it public, and are as ancient as the Spanish Inquisition. However, the piece also argues that Ocasio-Cortez’s self-ascription into Jewishness is valuable and significant precisely because it has unsettled American Jews in the present. This conclusion unproductively situates Ocasio-Cortez’s self-identification in competitive tension with normative (read: white Ashkenazi American) Jewish experiences. We believe this misses an opportunity to highlight the historic and contemporary intersections between Sephardic histories and Latinidad (Latino-ness) in the United States.

The identity narrative of a Puerto Rican Latina of Sephardic origins holds autonomous meaning and need not exist merely as an aggravating counter-narrative to white Ashkenazi American identity. Rather, Ocasio-Cortez’s present-day self-ascription into Jewishness is a function of Sephardic history and centuries of race formation in Latin America. When we place her story in the contexts of Sephardic and Latin American histories, her words illuminate often unseen expressions of identity among the Jewish diaspora in the Americas, while exposing the narrow paradigms of American, and American Jewish, histories.

Jewish ancestry, identity, and faith have never been coterminous nor consistent, even in single individuals—a phenomenon prominent in the post-expulsion Sephardic world. It is acknowledged that large numbers of conversos (Jews who converted, willingly or forcibly, to Catholicism in 14th and 15th century Iberia) and crypto-Jews (Iberian Jews who converted in name only) made their way to the Americas alongside Spanish, Portuguese, British, Dutch, and other colonial and trading empires. Oftentimes, they opted to settle in the far reaches of New Spain in order evade, with varied success, the long arm of the Inquisition. That those with Jewish ancestry—whether they kept their faith or not—intermingled with Europeans, Afro-diasporic, and indigenous people is beyond doubt. When Ocasio-Cortez announced her Sephardic ancestry at a Jews for Racial and Economic Justice Hannukah party this past December, she implicitly told us why Jewish identity in the context of Latin America is a messy one: “As is the story of Puerto Rico, we are a people that are an amalgamation; We are no one thing . . . We are black; we are indigenous; we are Spanish; we are European.”

Racial mixing, which is central to Latin American notions of the self and national belonging, also informs expressions of Jewish identity in the region. Racial classifications under Spanish colonial rule, known as the casta system, existed in a rigid hierarchy that placed those of white Spanish ancestry at the top and those of indigenous and/or African descent at the bottom. Beginning in the 19th century, however, Latin American nation-states began to embrace, albeit largely symbolically, the notion of racial hybridity as central to national identity and social belonging. State narratives of race mixing, or mestizaje, have had devastating consequences, primarily for their erasure of blackness, their continued privileging of European whiteness, and their valorization of indigenous peoples as historic rather than living, modern subject-citizens. Unlike in Europe or the US, where the integration of Jewishness into civil and public discourse is often done in pluralistic and piecemeal ways, Spain and Latin America give contexts to how Jewishness can be widespread and integral, albeit silenced. Placing Ocasio-Cortez’s narrative within the context of Latin American mestizaje helps clarify how Jewish ancestry does not necessarily intersect with notions of linearity, nor pure heritage, but rather, can exist as part of a broader constellation of races and ethnicities that have collided, often violently, across multiple centuries in the Americas.

The ways that understandings of mestizaje have obscured Jewishness in Latin America helps perpetuate American Jewish ignorance towards the full complexities of Latin American and Sephardic histories. The logical extension of this historical silence has meant the dominance of European models of Jewishness to understand Jewish identity globally. In much of contemporary Europe, efforts at integrating Jews within the framework of a national culture have seen some successes, but are increasingly threatened by the xenophobic ethno-nationalism gaining traction in recent years in places like Poland or Hungary. This differs from the way that mestizaje incorporates Jewish pasts in Latin America. In Latin America, conversos and crypto-Jews arrived alongside slaves and colonists, intermingling with the indigenous populations, situating Jewish ancestry within the many-branched family trees of today’s Latinx world.

The potential of many Latinx claimants to Jewish heritage could easily stoke American Jewish anxieties and concerns. The doubt and demand for proof levied on Ocasio-Cortez is indicative of not only zealous communal gatekeeping, and the same racist patterns that work to exclude Jews of color within Jewish places, but a fundamental misunderstanding of Sephardic history and the place of Jewishness in Latin America and among Latinx people. This conversation also manages to reveal some of the conceptual limits of understanding Jewishness in America: when ancestry is identity, someone who lacks a Jewish identity cannot claim Jewish ancestry, and someone who lacks Jewish ancestry cannot claim Jewish identity. An enormous burden of proof is put upon claimants, essentially telling them that they must follow the rules set by others in order to be “Jewish enough.”

The critical responses to Ocasio-Cortez’s story reveal not only the Eurocentric framework through which many American Jews continue to authenticate Jewishness, but more troubling, the living legacy of the Spanish Inquisition. Under the Inquisition’s limpieza de sangre (blood purity) doctrine, conversos remained politically and economically marginalized as punishment for their impure past, the stain of their Jewish, or Muslim, blood; crypto-Jews lived in fear and silence, practicing inherited Jewish customs, without knowing why. Ironically, intercommunal Jewish gatekeeping in the United States has adopted a similar stance as it regards “purity,” namely, an intolerance for recognizing “messier” Jewish experiences and histories as natural and inseparable elements of the diasporic condition. In turn, these cyclical patterns of Jewish gatekeeping have relegated the narratives of Sephardic Latin American Jewish heritage to the margins, despite their centrality to Jewish histories in the Americas. Ocasio-Cortez’s Jewish heritage is a teaching moment, an opportunity for a great many of us to see through historical silences and the whitewashing of Jewish identity, towards a clearer expression of the Jewish diaspora in the Americas.

Maxwell Ezra Greenberg is a fifth-year doctoral candidate in the César E. Chávez Department of Chicana/o Studies at UCLA, and the 2018-19 Skirball Fellow in Modern Jewish Culture.

Max Modiano Daniel is a PhD candidate in History at UCLA and the director of ucLadino, a student group at UCLA that organizes conferences and workshops on the study of Sephardim and Judeo-Spanish.