All Talk

The coexistence camp Seeds of Peace prides itself on bringing Israeli and Palestinian teenagers into a fruitful dialogue process. But alumni and staff now say that the model does more harm than good.

IN THE SUMMER OF 2014, as Israeli bombs rained down on Gaza during the military incursion known as Operation Protective Edge, Salma Faysal, a 17-year-old from the area, was at sleepaway camp in rural Maine. Faysal was a second-year camper at Seeds of Peace Camp, a coexistence initiative that brings Israeli and Palestinian teenagers together each summer on the shores of Pleasant Lake, an hour northwest of Portland. Every day for a little under two hours, in facilitated dialogue sessions squeezed between regular camp activities like basketball and sailing, participants discuss their experiences on opposing sides of a geopolitical conflict; beyond those sessions, staffers discourage political conversation. But in 2014, as Palestinian campers struggled to reach family members back home—cell phones are prohibited at camp—something gave way.

In the middle of the July session, Faysal and the rest of that summer’s Palestinian delegation left their regularly scheduled activities, put on keffiyehs, and silently protested in solidarity with Gaza on the camp’s central lawn, near a green shed lettered with the words “This is the field”—a reference to a cloying English translation of a Rumi poem that begins, “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.” The demonstration was virtually unheard of in the camp’s history. Camp leadership reprimanded the Palestinian teens, according to Faysal and Hamzeh Ghosheh, a Palestinian counselor and Seeds alumnus, telling them that regulations dictated they should be sent home. But, Faysal explained, “they couldn’t send home a whole delegation.”

The incident foreshadowed a turning point at Seeds of Peace. Partly to maintain the cooperation of participating governments, the camp has remained staunchly apolitical, touting a mission of developing youth leadership for global change but avoiding taking a position on particulars like military occupation or borders. But in the past few years, Seeds of Peace’s year-round staff began calling for sweeping changes to this approach, including an overhaul of the camp curriculum. (Full disclosure: I was a counselor there in 2014 and 2016, though I’ve never been involved in staff organizing.) The organization’s leadership pushed back, creating a dispute that came into public view early in 2020, when camp director Sarah Brajtbord—who had been involved with Seeds of Peace since her own time as a camper in the early 2000s—announced in a blistering Facebook post that she had been fired by a board of directors intent on stifling “long overdue change.” More than 100 of the camp’s seasonal staffers responded with a letter to the board demanding that the body become more accountable to and representative of the community it serves, hire a third party to investigate possible retaliation against Brajtbord by a board member, and—most dramatically—cancel camp that summer while the organization reconceived its vision. That last demand quickly became moot: Seeds of Peace announced last March that in-person sessions would be canceled for 2020 due to the coronavirus. But the fate of future summers remains in flux.

Seeds of Peace was founded in 1993, the year of the first of the Oslo Accords, and quickly became emblematic of that era in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. At the close of the camp’s very first session, campers—or “Seeds,” in the organization’s parlance—traveled to Washington, DC, to attend the signing of the accord on the White House lawn. A year later, another group of Seeds visited the White House, where President Bill Clinton told them, “The image of you smiling together, of you singing together, of you being together will spur us on to try to make sure that the future . . . will be a future you share together.” (Clinton is still listed on the organization’s advisory board, along with a handful of other Oslo-era figures, most of whom are now deceased.) For years, participants met with State Department officials like Madeleine Albright; in remarks to campers from 1999 aired on C-Span, the former secretary of state called Seeds of Peace her “favorite group.” Such endorsements gave the camp early momentum, which has subsequently inspired countless articles in the press. “Now I do think that there will be peace between Israel and Palestine,” a Palestinian camper named Mirna Ansari told the BBC in one typical piece. “If we as teenagers believe that, then when we grow up we will work on it.” (Today, Ansari manages Seeds’s Palestinian programs, alongside a number of colleagues across the organization’s various international offices who first got involved as campers.)

The promise of Oslo has faded as its purportedly temporary provisions for managing the occupation have instead furthered the occupation’s entrenchment—yet Seeds of Peace endures as a potent symbol of a binational peace process toward a two-state solution. As recently as 2014, weeks after the official end of the Gaza War that killed more than 1,000 Palestinian civilians, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, who was in New York for the UN General Assembly, told an audience at Cooper Union, “To those who say peace between Israelis and Palestinians is impossible, I say, let them visit America. I say, let them visit Maine.” But, like the peace negotiations that inspired Seeds of Peace a generation ago, the structure of the camp’s Middle East program has worn thin. Alumni and staff have openly challenged the dialogue method at the core of the program and the effectiveness of that method in an asymmetrical conflict. These rifts have already helped change the face of the organization: There have been numerous resignations and layoffs in the year since Brajtbord’s departure—some a result of the upheaval and some due to Covid-19—reducing the nonprofit’s staff by roughly 20%. Conversations with 36 people, including alumni, current and former staff, and donors—many of whom have requested anonymity because of continuing ties with the organization—have painted a picture of a program in turmoil: caught between a dialogue model built to address conflict without discussing power, and an alumni base increasingly disillusioned with its effects.

In 1993, at a Washington, DC, dinner party, a well-connected American foreign correspondent named John Wallach announced to the assembled Egyptian, Palestinian, and Israeli officials that he was starting a summer program to build bridges between Israeli and Arab youth. Wallach extracted verbal agreements from the diplomats, putting their assent on record with the White House press corps the next day. “He called everyone; he engaged the movers and shakers at the time,” Seeds of Peace co-founder and board member Bobbie Gottschalk said. Later that year, President Bill Clinton was scheduled to facilitate peace talks between Palestinian Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. Though critics like Edward Said foresaw the Oslo Accords’ potential to irrevocably damage the cause of Palestinian statehood, many American liberals believed that the resolution of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict was on the horizon, and that coexistence between peoples would soon become the region’s most pressing concern.

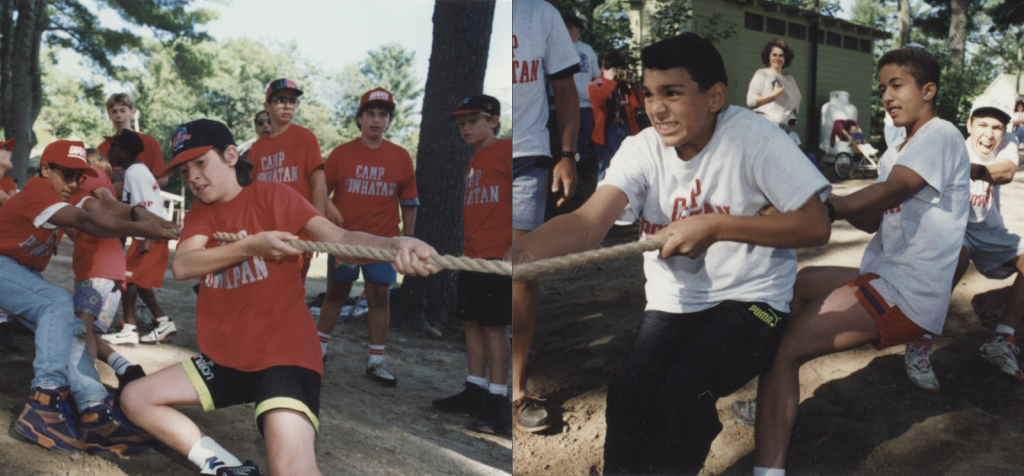

That August, Wallach brought almost 50 teen boys from Israel, Palestine, and Egypt to Maine for a two-week session on the grounds of Camp Powhatan, where his own son had been a camper for eight summers. Wallach’s stated goal for his program was straightforward: He hoped that every participant would “make one friend from the other side.” Campers at Wallach’s session spent their days doing regular camp activities; in the evenings, Wallach supervised facilitator-led dialogue about the conflict. At the end of the program, the Seeds were asked how the conflict should be resolved, and agreed on the need for a Palestinian state. This basic model for the summer sessions persists to this day, and has been expanded to include other conflicts: Alongside its flagship Middle East program, Seeds of Peace now runs programming for Indian and Pakistani teens during the two- to three-week international session, as well as a domestic session focused on issues like racism and economic inequality and open to participants from Maine and major US cities.

The organization has long promoted a romantic image of the camp, which Wallach called “the miracle in the Maine woods” in 2002 remarks to state lawmakers, coining a slogan its supporters have often repeated. At orientation, counselors are introduced to Wallach’s vision that one day, Israelis and Palestinians who met at the camp as youth would reunite at the negotiating table as representatives of their respective homelands. Some aspects of this dream came true. A 2014 study by researchers at the University of Chicago found that Israeli and Palestinian campers left Maine with newly trusting feelings toward one another, and that the most positive attitudes were expressed by campers who had forged at least one close friendship with someone from the other delegation. Another study—conducted by Ned Lazarus, the former director of Middle East Programming at Seeds of Peace, for his doctoral thesis—found that around 17% of graduates from the program’s first decade were involved in “peacebuilding” work later in life. Some participated in advocacy groups, academia, or media; some, just as Wallach hoped, have worked on Israeli and Palestinian final status negotiation teams. A number of Seeds have gone on to create initiatives of their own: Micah Hendler’s Jerusalem Youth Chorus applies a Seeds-like dialogue model to a choir of Israeli and Palestinian singers; Lior Amihai founded Yesh Din, a group that documents human rights abuses against Palestinians by Israelis. Lazarus concluded that the Seeds model works mostly on the micro level. “We [in the peace field] don’t have illusions that this somehow by itself can end the occupation or end violence—reality is much larger than what we’re able to do,” he cautioned. Yet on the individual level, the organization seems to have left a mark.

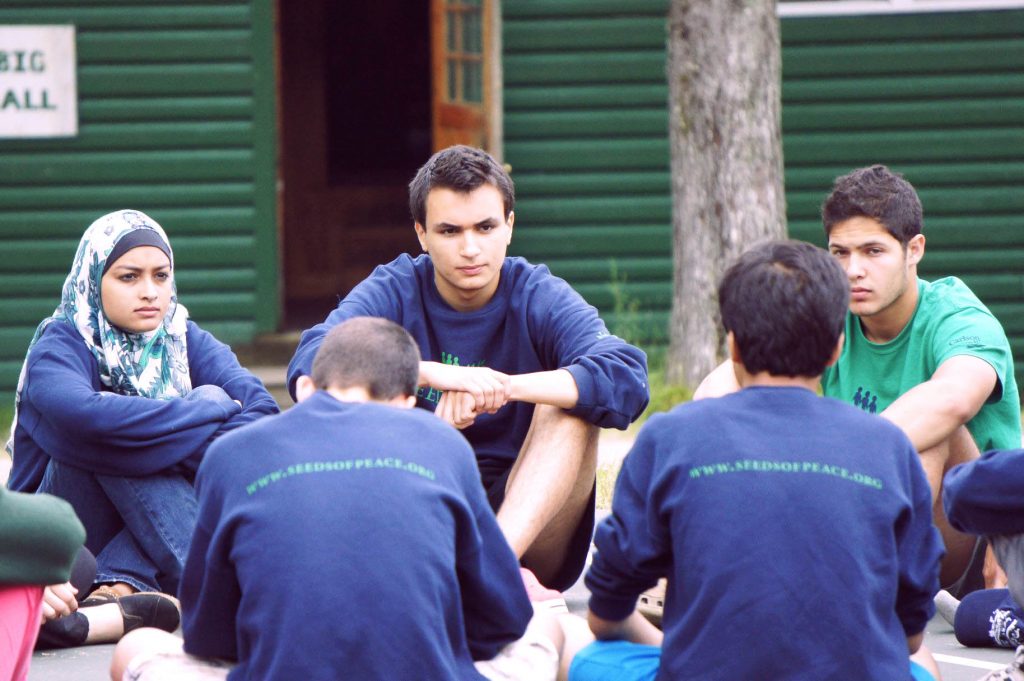

“Dialogue” is the byword of all Seeds of Peace programs. In colloquial and political usage, the term can refer to any discussion between two parties with different interests intent on reaching a compromise. The term is used for conversations between bosses and union leaders, or between rival gangs, or when two world powers meet on a matter of statecraft: The Oslo Accords, for instance, purported to engage in dialogue to convert Palestinian and Israeli leadership from opponents to partners in a two-state project. Dialogue at Seeds of Peace is flexible; no two groups will undergo the same process, and each “dialogue hut”—the small wooden cabins where discussion takes place—works at its own pace. Facilitators might suggest different activities based on the needs of the group, such as “fishbowl,” in which part of the group moves to the edges of the room, listening to a conversation happening among an inner ring of campers without interjecting, or a “privilege walk,” where campers stand in a row as the facilitators read off different kinds of life experiences, inviting campers to step forward if the experience applies to them.

“When dialogue is heating up, tears are common during meals and free time. You think to yourself, ‘How am I supposed to get this teenager to play volleyball when a half an hour ago someone accused them of being a terrorist?’ ”

Seeds counselors are trained to gently shut down “political” discussions outside the dialogue huts, in part to create a respite from the intense daily dialogue sessions and to ensure that those conversations take place in a dedicated, supportive environment. But this practice can be a painful experience for campers, who are left with few opportunities to unpack the taxing experience of dialogue itself. “Seeds of Peace would just leave us devastated after each dialogue and expect us not to talk about it with our friends at camp or call our parents to vent,” said Faysal. Counselors are left to deal with the emotional fallout. “When dialogue is heating up, tears are common during meals and free time,” said former counselor Jake Lachance. “You think to yourself, ‘How am I supposed to get this teenager to play volleyball when a half an hour ago someone accused them of being a terrorist?’”

Like other conflict resolution programs of the era, the model used at Seeds of Peace Camp is derived partly from a theory called the “contact hypothesis,” outlined by psychologist G.W. Allport in his 1954 book, The Nature of Prejudice, published the year the Supreme Court ruled against school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education. Allport suggested that direct interactions between people of different groups could reduce prejudice and promote integration if the encounters met a number of conditions: equal status and common goals between members, the support of the participants’ governments or societies, and structured activity. Intergroup contact research sparked decades of scholarship and made its way into the Middle East “coexistence” sphere; in the 1970s, for instance, psychologist Herbert Kelman—a colleague of Allport’s—brought Israeli and Palestinian intellectuals together for “problem solving workshops” secretly conducted at Harvard. John Wallach, as a former international news editor, had followed Arab–Israeli negotiations extensively and was enmeshed in the DC milieu of foreign policy professionals at a time when, as Lazarus explains in his research, these theories of intergroup contact were highly popular there.

From the beginning, Seeds of Peace could not meet many conditions of Allport’s contact hypothesis, which was itself later rejected by social psychologists increasingly skeptical of the idea that encounters based on humanizing individual participants do much to ameliorate group prejudice. On paper, Israeli and Palestinian campers are treated equitably. But there is no equity at camp when there is no equity at home—a reality dramatized by the experience of the Palestinian delegation during Operation Protective Edge in 2014. Only two Gazans made it to camp that year: Faysal and 16-year-old Mustafa Al-Shawwa, who left Gaza three weeks after the bombing started, and headed to Cairo on his Moroccan passport so that he could travel with the Egyptian delegation to Maine. Al-Shawwa returned home to find four family members’ homes destroyed by IDF bombing. “After an amazing 22 days at the camp, I realized it’s not that amazing after all,” he wrote in a letter to Noa Posen, an Israeli teen he had befriended at Seeds of Peace, that was excerpted in +972 Magazine. “All my family in Gaza was in danger, waiting for death every minute.”

Alumni and staff said that ignoring obvious inequalities between campers was often not only ineffective but harmful. “There’s a dynamic where Palestinian kids are asked to expose their trauma wounds in hopes that the Israelis will understand them,” said a former Seeds facilitator who requested anonymity because they signed a nondisclosure agreement with the camp. A Seeds alumnus who likewise spoke on condition of anonymity due to her ongoing relationship with the organization noted that ignoring the inequality of experiences also shortchanges Israeli campers: “It really takes away an opportunity for solidarity and action from Israelis, because they’re supposed to be equals. Seeds of Peace can make them more complacent because now they’ve already heard the other side.”

“There’s a dynamic where Palestinian kids are asked to expose their trauma wounds in hopes that the Israelis will understand them.”

One difficulty stems from the fact that inter-national programs at Seeds of Peace are forced to navigate the demands of multiple antagonistic foreign governments. The education ministries of both the Palestinian Authority and Israel had previously been involved in recruiting campers for Seeds of Peace. But in the past five years, the Palestinian Authority has completely withdrawn its participation. In 2018, in an attempt to correct the imbalance this created, Seeds of Peace ended its collaboration with the Israeli Education Ministry; the organization now selects both Israeli and Palestinian participants independently. Both delegations face ostracization in their home communities, but this is especially true for Palestinian Seeds. “People would say we normalize relations with Israel and reduce the Palestinian struggle and plight to a ‘conflict’ that is equal-sided,” said Faysal.

Unlike the international programs at Seeds of Peace, the camp’s domestic program has never involved negotiations with the likes of foreign education ministries—and the difference between the sessions was obvious, former staffers said. In 2014, soon after Palestinian campers were reprimanded for demonstrating, staff orientation for the domestic session began (counselors remain consistent over the course of a summer, while groups of campers rotate in and out). Suddenly, counselors who had spent weeks shutting down political discussions were encouraged to take stances against patriarchy and racism. Multiple counselors described a situation in which it would have been hard to enforce a gag order on political discussion during the domestic session even if they’d tried—which suggested an insidious double standard. “We were talking about race and gender and sexuality and immigration policy, and people were like, ‘You can’t shut kids up when they’re talking about that stuff,’” said Bahira Hesham, an Egyptian camper and then counselor at Seeds of Peace. “But it’s okay to shut Palestinian kids up?”

Though ostensibly founded to address a political conflict, the organization has tended to avoid making plainly political statements in order to recruit what it calls a “big tent” of campers. But in practice, former staff members said, this has typically meant the ability to attract more conservative Israelis at the expense of more politically diverse Palestinians, Egyptians, and Jordanians. An American Seed raised in a household “deeply committed to Zionism,” who requested anonymity because he continues to work in the peace field, pointed out that he probably wouldn’t have attended Seeds of Peace in the first place if it was framed as an anti-occupation program. “The fundamental question is, how can you do co-resistance work while also bringing people to the table who aren’t already on board?” he said.

But even the possibility of swaying mainstream Israelis may belong to a bygone era. Support for a two-state solution among both Israelis and Palestinians is at its lowest point in a generation, as is identification with the Israeli left: Young voters are far more likely than their parents to identify with the right-wing Likud, and traditional left parties like Labor and Meretz hold only six Knesset seats (of 120) between them. In a sign of the times, Tel Aviv University announced last year that it would shut down its Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research amid concerns of waning relevance. In a flagrant abandonment of the “dialogue” model, the Trump administration developed its plan for the region without inviting any input from Palestinian authorities, proposing what has been interpreted as a de facto endorsement of Israeli apartheid. At the event in January 2020 to unveil the final part of the US plan, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reiterated his plans to annex the Jordan Valley and all Israeli settlements. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, who was not at the event, later reiterated his claim that, in light of the annexation plans, the PA would no longer abide by agreements like the Oslo Accords.

For some within the peace field, the dire state of the conflict only makes their work more urgent. “In 2020, Israelis and Palestinians working together as peers is more radical and risky than at any point in their history, swimming against the trends of racism and separation,” said John Lyndon, the executive director of Alliance for Middle East Peace, an umbrella organization for people-to-people initiatives that includes Seeds of Peace. “With the erosion of the two-state paradigm, it is also more vital than ever.” But for observers like Tariq Dana, a policy analyst at the Palestinian think tank Al-Shabaka, a coexistence field built atop a crumbling peace process is on too-shaky ground. These coexistence organizations “served in an era when the international community invested in the two-state solution,” he said, and now that that investment has evaporated, they are more irrelevant than ever. A Seeds staffer who requested anonymity because they had signed a nondisclosure agreement, summed up the program’s predicament: “We’re not forward-thinking enough for the reality, but the reality is so oppressive that we’re already too radical to exist.”

A Seeds staffer summed up the program’s predicament: “We’re not forward-thinking enough for the reality, but the reality is so oppressive that we’re already too radical to exist.”

Many Seeds of Peace staff members say that the Middle East program, which has changed little since the 1990s, has not adjusted to these circumstances. In 2019, Bashar Iraqi, then the Palestinian programs director, and four other Palestinian staffers circulated a memo within the organization calling for Seeds to make its Israeli programming more occupation-oriented and to take a firm stance against oppression. “Meeting with the enemy isn’t a fun summer camp activity; the fun and the beautiful lake fade away in front of reality and truth,” it reads. “The most pressing question we need to answer as an organization is why? . . . A picture that shows the oppressed with the oppressor can generate money, yet does it generate peace?” The memo rallied staff around two demands: Focus international dialogue less on broad national narratives and more on power dynamics, and clarify the organization’s political stance and vision. The reforms were supported by staff leadership at the highest levels, said a staffer who asked to remain anonymous because they signed a nondisclosure agreement. “But once the board got involved,” they said, “there was hesitance.”

A Seeds of Peace staffer named Gregory Barker, who wrote the dialogue manual for the domestic program and, until he was laid off last year, led an evaluation process for all of the camp’s dialogue programs, said many on staff would describe their demands as a shift from coexistence to co-resistance. Barker cited the dialogue model described by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire in his seminal work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, as an example of the latter. Instead of creating understanding between the oppressor and the oppressed, Freire emphasizes building solidarity among the oppressed themselves. “There’s a real limit to how many people from the dominant group can be in a conversation for it to remain productive,” Barker said. He added that dialogue activities that unpack structural power along lines of race, gender, and class force people to occupy dominant and nondominant positions at different moments. “If you have it framed as two countries—two delegations—then you know your identity going in,” Barker explained. But in the more flexible dialogue model, like the one used in the domestic program, “participants may find themselves building coalitions with people on one topic whom they disagree with on another.”

In the Facebook post Sarah Brajtbord wrote after her removal, the former camp director pointed to the potential for dialogue to become a tool for liberation and collective action, using the hashtag #coresistanceNOTcoexistence—a framing that has been part of staff demands as well. Barker echoed this sentiment, evoking a twist on a classic quote by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that has itself become idiomatic: “Yes, the arc of history bends towards justice—if we bend it.”

CRITIQUES OF SEEDS OF PEACE have gone beyond its dialogue model to indict the structure of the organization, putting camp staff directly at odds with some of the organization’s major donors, several of whom sit on the board of directors. The unusually large board—36 members, nearly half of whom have worked in the finance industry—has come under particular scrutiny. In Brajtbord’s Facebook post, she contended that the board did not reflect “the communities we serve or the culture we create as an organization. There are no young people, there is only one Seed, they are predominantly wealthy and white, a disproportionate number would identify as Zionists, none of them live outside of the US and UK, and whoever has the most money in the room has the most power.” Brajtbord’s withering remarks sparked debate in the flood of comments that followed, perhaps most predictably around the question of board members’ commitments to Zionism. An alumnus named Dean Teplitsky, for instance, objected that Brajtbord had “labeled [the board], out of personal frustration, as ‘Zionist, white, and rich,’ and by that put Zionism in one line with the most privileged and hated groups in America.” Others, however, welcomed the opportunity to bring Zionism into a broader conversation about power. “When we set up dialogue as roughly two groups of people, one of whom owns the land, and sit them in a room and say ‘talk,’ that implies that the problem is that people are not getting along,” Gregory Barker said in an interview. “That’s not the problem. The problem is settler colonialism.”

Brajtbord’s comments also pointed to a structural problem: the presence of American delegations of campers at Seeds of Peace Camp’s international sessions, often including major donors’ children. Staffers familiar with program recruitment compared it to that of a prestigious college. On the one hand, the organization has always sought to recruit youth with strong leadership potential, and admissions can be extremely competitive. On the other, Seeds’s funding model depends heavily on bringing funders’ children to camp, where they often take part in either the Middle East or South Asia dialogue—an awkward recapitulation of US foreign policy in miniature. Movie director J.J. Abrams’s family foundation donated $10,000 to Seeds of Peace in 2016, the year his daughter attended camp, and $70,000 over the course of the next two years—a total donation that would cover attendance for about 11 campers. In 2010, the year after New Yorker editor David Remnick’s son attended camp, Remnick gave the keynote speech at the spring fundraiser, which raises over $1 million for Seeds of Peace each year. An American Seed whose parents are donors (and who requested anonymity for this reason) shared discomfort with the purpose of the American delegation. “I felt that my role at camp was to enable others to be there through my parents’ donations,” they said. “I didn’t feel like the program was built for me.”

Concerns about unchecked donor and board power were inflamed by a fight centered on members of the Toll family, who are major Seeds of Peace donors as well as the camp’s landlords. Robert Toll—co-founder of Toll Brothers, one of the largest house-building companies in the US—sits on the nonprofit’s board along with his wife, Jane. The couple’s son Jake, 40, worked at Seeds of Peace Camp for several years, serving first as a counselor, then as waterfront director; his official employment ended in 2013, but he remained a presence at camp even without a formal role. He also personally donated between $75,000 and $148,000 to the organization from 2016 to 2018, according to the nonprofit’s annual reports. According to staffers, Toll’s time at the camp elicited multiple complaints to leadership regarding inappropriate gender-based comments and a lack of clarity around his role. “We were never sure what we could say no to with him,” said Nate Madeira, a former waterfront director.

Early in 2019, after the complaints, Brajtbord declined to allow Toll to work directly with campers. Another staffer subsequently lodged a formal complaint against Toll with the organization’s HR department, accusing him of gender discrimination and gender-based harassment of employees, and alleging that Jane Toll had sought retribution against people who complained about her son’s behavior. Several months later, Brajtbord was removed from her position, not by her direct supervisor, but by a not-publicly-named board member acting in a managerial role. Rather than accept another assignment within the organization, she quit. In her Facebook post in January 2020, Brajtbord alleged that the board had been given an “ultimatum” to remove her or risk losing a significant portion of its funding. (Jane Toll did not respond to requests for comment; Jake Toll said in a phone call that he had never heard of the formal complaint and did not respond to an emailed list of questions about allegations made by staffers.)

For staff, who had long drawn attention to the need for better governance practices, the alleged circumstances of Brajtbord’s dismissal were the final straw. They successfully demanded in their letter to the board that a third party investigate claims of retribution related to complaints about Jake Toll, according to staffers familiar with the matter. “The review found that Seeds of Peace has been operating in accordance with our policies, but that there is room to improve our management and governance practices,” Seeds of Peace spokesperson Eric Kapenga said in May. (Kapenga declined to comment directly on the accusations against Jake Toll.) Both Brajtbord’s post and the staff letter also took aim at the board for “hid[ing] . . . big questions,” as the former put it, in a long-term strategic visioning process. The staff letter concluded that “it would be irresponsible to continue bringing young people to camp this summer when the organizational vision is so unclear.”

In February 2020, the director of the Israeli Seeds program, Maayan Poleg, announced her resignation in a Facebook post. “If these conversations are held solely for the purpose of narratives and ideas to be exchanged, then we are contributing to the preservation of the status quo,” Poleg wrote.

True to form, the board replied to the staff letter in part by inviting the senders to dialogue with them, a staffer familiar with the discussions said. But the damage had seemingly been done: In February 2020, the director of the Israeli Seeds program, Maayan Poleg, announced her resignation in a Facebook post. “If these conversations are held solely for the purpose of narratives and ideas to be exchanged, then we are contributing to the preservation of the status quo,” Poleg wrote. “[T]he attempt to create a space that is neutral . . . in a context that is extremely political is the same as encouraging blindness and preservation of reality as it is today.” Ghosheh, the Palestinian alumnus who joined camp staff in 2014, has also severed ties with Seeds of Peace. In late 2019, Ghosheh said, he began getting calls from the organization’s leaders, staff, and board members, all wanting his opinion on the internal disputes. As one of the few Palestinians who’d remained active in the organization, he got the sense that each person wanted to strengthen their side of the argument with his endorsement. “I got tired of being used for my identity without being allowed to use my insight to change anything,” Ghosheh said.

Over the course of last year, the organization began to make bolder political statements, though it did not describe how the new stances would apply to the organization itself. In the first half of 2020, a “values” page on the organization’s website was updated: “As an organization, we affirm our opposition to dynamics, institutions, and structures that are obstacles to peace, including Racism, Sexism, Classism, Political Violence, Colonialism, Military Occupation, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia. We support our alumni as they work to end these obstacles.” In February, in another uncharacteristic move, Seeds of Peace sent an email signed by board member Janet Wallach, widow of the camp’s founder John Wallach, criticizing Trump’s Middle East plan. In a June statement, the organization publicly opposed Israeli annexation of the West Bank and US support for it. In August, the organization announced in an email to supporters signed by the recently named executive director, Father Josh Thomas, that it was creating an entirely new strategic plan “[focused] on developing courageous leaders, building solidarity across lines of difference, and working to create a more just and inclusive world.” Though the organization did not run in-person camp this year due to the pandemic, it has continued to invite former Seeds and staff to participate in dialogue, including online focus groups, about the nonprofit’s direction. In recent fundraising emails and an NPR interview with the US programs director, the organization has backed further away from the romantic image of camp, describing the program as difficult and painful.

The Seeds community is watching closely to see whether changes to the organization’s external communications will translate into material changes to its programs. Sarah Erwin, an alumnus and former counselor and facilitator who signed the staff letter, said she’s disappointed that the nonprofit has adjusted its public image only after the recent upheaval: “It took the risk of losing this entire organization for the board to consider this important to do after 25 years.” Hesham, the Egyptian alumnus and former counselor, believes that the organization has shown enough openness in recent months that it could still manage to meaningfully overhaul its programming. “It’s not over,” she said. “But do I think the program is the best use of resources to address these issues? I’m not sure.”

Yet even some alumni calling for structural change at Seeds of Peace said they’re grappling with the paradox that the camp was a catalyst for developing their understanding of power structures in the first place. The alumnus who criticized the program for making Israeli campers complacent acknowledged the difficulty of her position. “I was introduced to this whole culture at Seeds,” she said. “My best friends in the world are from there.”

This story has been updated to clarify the year in which some events occurred.

A previous version of this story mistakenly identified Salma Faysal as being from Ramallah, rather than Gaza.

Jess Rohan is a journalist in Cairo.