A Critic Compromised

Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer? contains two irreconcilable Adam Kirsches.

Discussed in this essay: Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer?: And Other Essays, by Adam Kirsch. Yale University Press, 2019. 232 pages.

ADAM KIRSCH’S Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer?—a new collection of essays, many originally published in Tablet, The New Republic, Poetry, and elsewhere—seems to have been written by two utterly irreconcilable Adam Kirsches. One is a perceptive critic with an enviable wealth of knowledge about poetry, Judaism, and Jewish literatures, which he deploys in informative, energetic pieces of literary criticism. The other writes mostly about politics and current events, in essays marred by intellectually lazy analysis that one would expect the other Kirsch to abhor. That these divergent writers converge under the same byline is almost inconceivable.

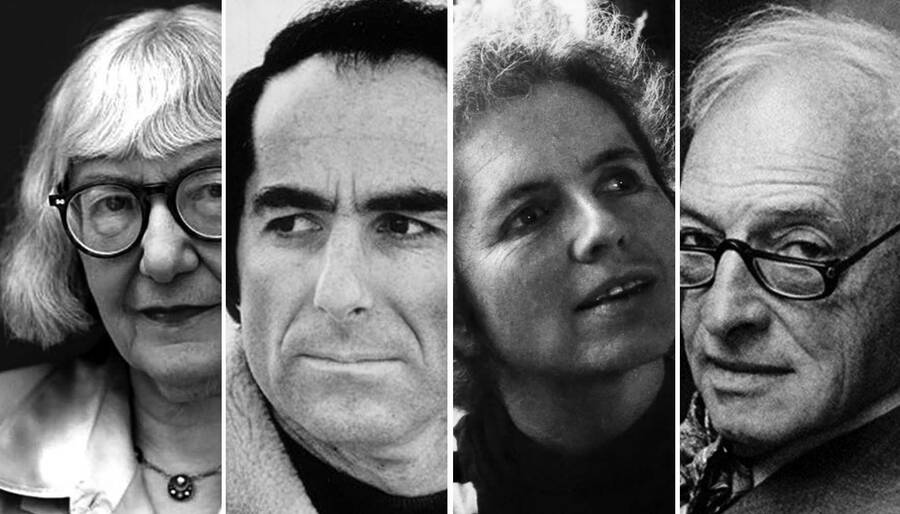

The collection begins with the work of this first, more thoughtful Kirsch. The opening, titular essay is a probing look at some midcentury titans of American literature—including Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, and Lionel Trilling—and their uniform rejection of the idea that they should be categorized as “Jewish writers.” With the question of who wants to be a Jewish writer easily handled (the answer being, apparently, nobody), Kirsch explores possible reasons why. One theory, which comes via Cynthia Ozick’s “Toward a New Yiddish,” is that “[t]here are no major works of Jewish imaginative genius written in any Gentile language, sprung out of any Gentile culture.” Kirsch contextualizes this claim by adding that “Ozick does not mean that there have been no great Jewish writers in non-Jewish languages . . . [r]ather she meant that when Jews write in non-Jewish languages, they no longer possess a specifically Jewish imagination.” Kirsch never rejects Ozick’s argument outright, but his own views are more diplomatic, and center on American Jews’ widely varying relationships to Jewishness:

The same person might feel not at all Jewish when alone in a forest, and very Jewish when in a synagogue—or vice versa. He might feel most Jewish when taking pride in Israel or when boycotting Israel. It is because American Jewishness is no longer a simple fact of language, community, or belief that it has become a matter of feeling.

This line, which appears in the essay’s final paragraph, is more whimper than shout, but it’s a satisfying conclusion to Kirsch’s methodical search for an answer to the question of why the title of “Jewish writer” has been so roundly rejected by those who might bear it.

After demonstrating his ability to synthesize trends across a range of writers and works, Kirsch focuses his critical faculties on a single work: Robert Alter’s translation of The Book of Psalms. “One of the tasks Robert Alter undertakes,” Kirsch writes, “is to evacuate the covert theological assumptions of the Authorized Version”—that is, the King James Version, the translation most familiar to many English readers. As Kirsch shows, Alter accomplishes this task not only via obvious strategies—such as the removal of any mention of “soul” or “salvation”—but also through smaller choices that play an equally important role. For instance, Kirsch examines Alter’s capitalization in his rendering of Psalm 2: “Where the King James version has ‘Thou art my Son,’ leaving no doubt that the second person belongs to the Second Person of the Trinity, Alter has ‘You are My son,’ restricting the honorific capital to the speaker.” This is an elegant and efficient slice of criticism, explaining the relevance of a technique while also commending Alter for his attention and vision. Throughout the essay, Kirsch is also careful to clearly make the point that, though Alter’s translation makes the psalms more useful for Jewish readers, his main goal is to translate them as literature. The success of this endeavor, Kirsch astutely notes, is not in the psalms’ language, per se, but “in their music, which breaks just as deliberately with the expectations bred in English readers.”

The Kirsch of these initial essays—as well as others, such as “The Faith of Christian Wiman,” “Kay Ryan: The Less Deceived,” and “Stefan Zweig at the End of the World”—displays clarity, erudition, and a deep concern with treating the texts under consideration thoughtfully and fairly. But when Kirsch turns his attention to more political matters, this insight, curiosity, and care all but disappear. In “Poetry and the Problem of Politics,” Kirsch attempts to argue that poetry “is the exact opposite” of liberalism because poetry “thrives on glorious depictions of extraordinary individuals,” whereas liberalism “puts the many above the one and right above might.” The essay is predicated on a series of generalizations and strawmen. For example, the opening line reads, “Poetry and politics seem like they ought to be opposites,” which nobody believes, and which Kirsch says for the sole purpose of contradicting the claim a few lines later.

“Extension of the Domain of Struggle,” the title of which is lifted from a Michel Houellebecq novel, describes how social media is bad for art, using arguments that are uniformly predictable and boring. Kirsch opens the essay by arguing that the release of Keith Gessen’s debut novel, All the Sad Young Literary Men, spurred an online response consisting of “extraordinarily virulent attacks,” though Kirsch cites none in particular and gives no sense of their scale. This ordeal, he argues, “exposed literature for what at bottom it really is: a power struggle.” But he gives the reader no reason to understand the online reaction as a true “power struggle” or to consider this incident exemplary of the essence of literature as such. To decry the democratization offered by the online world as harmful to literary culture, he overstates the digital world’s hierarchy demolition: “Online,” he writes, “there are no mediating institutions—no editors, magazines, publishing houses, critics—with the power to confer or protect literary reputation.” This is, of course, demonstrably untrue.

Matters get much worse in “Rosa Luxemburg and Isaac Deutscher,” in which Kirsch’s worst impulses dominate; one can’t help but hear the faint sound of an axe being ground in the distance. The essay, which fuses two separate, previously published pieces, sets out to categorize Luxemburg, an extremely significant socialist thinker and activist who was executed in Germany in 1919, and Deutscher, a Marxist writer known for his biographies of Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin, as Jewish thinkers who cannot imagine “an ideal society that is not predicated on the elimination of Judaism.” Kirsch considers Deutscher’s most famous work, “The Non-Jewish Jew,” an essay on the intellectual legacy of Luxemburg, Karl Marx, Leon Trotsky, Sigmund Freud, and other significant thinkers of Jewish descent who rejected their Judaism in similar ways.

Kirsch writes that “[t]he freethinkers and revolutionaries [Deutscher] cites experienced Judaism as a prison or a ghetto,” a claim that baselessly twists Deutscher’s observational critique of Judaism as a limited analytical framework into something much more menacing. Kirsch goes on to criticize Deutscher’s framing of Freud’s work:

Deutscher praises Freud, for instance, “because the man whom he analyzes is not a German, or an Englishman, a Russian, or a Jew—he is the universal man . . . whose desires and cravings, scruples and inhibitions, anxieties and predicaments are essentially the same no matter to what race, religion, or nation he belongs.” But of course, the people whom Freud analyzed were mainly Jews. This does not necessarily mean they did not have the same “desires and cravings” as everyone else—though then again, maybe it does mean that.

Deutscher de-emphasizes the Jewishness of Freud’s patients not out of some nefarious, targeted anti-Judaism, as Kirsch seems to suggest, but to commend Freud’s universalist humanism. Kirsch’s reading of this line feels especially disingenuous coming from someone who wrote, in the collection’s titular essay, “To call oneself a Jewish writer might seem to imply that one loves, hates, and so on in a different way from people who are not Jewish, and of course this is not the case, any more than it is the case with any ethnic or religious distinction.” Nowhere in the book does Kirsch justify why he is entitled to such a claim when Freud and Deutscher are not.

Worse still is Kirsch’s treatment of Deutscher’s essay “Who is a Jew?”. Here’s how Kirsch describes the essay:

In “Who is a Jew?” [Deutscher] writes, “it is strange and bitter to think that the extermination of six million Jews should have given a new lease of life to Jewry. I would have preferred the six million men, women, and children to survive and the Jewry to perish.” Jewry—that is, Jewishness, deserves to perish, Deutscher believes, because Marx was right, and Judaism is just another name for capitalism.

This is a bizarre and unfair summation; Deutscher’s quote is plucked out of context, its meaning distorted beyond recognition. In the rest of his essay, Deutscher argues that the abolition of capitalism would mean liberation for the Jewish people and the destruction of much of the structure that propped up 20th-century antisemitism.

What Deutscher is arguing in “Who is a Jew?” is that the trauma of the Holocaust is at the center of a reanimation of the Jewish community. This is made clear when Deutscher declares that he is a Jew “by force of [his] unconditional solidarity with the persecuted and exterminated” and “because [he feels] the Jewish tragedy as [his] own tragedy.” Kirsch mentions this framework earlier in the essay but seems not to recall it when chastising Deutscher, using the distance between its utterance to gain some clearance for his argument. Clearly, Kirsch is no fan of Deutscher’s work, but he’s only able to critique it by misrepresenting Deutscher’s own words. If Kirsch had embarked on his critique in good faith—in the spirit that animates his more literary work—it would have been a more difficult (and more interesting) project.

As the book goes on, this myopia does not abate. In “Angels of Liberalism,” Kirsch uses the occasion of a new run of Angels in America to write about the state of antisemitism in the West in the 21st century. The play’s fictionalized version of Jewish lawyer Roy Cohn—famous for prosecuting the Rosenbergs and for advising Joseph McCarthy (and, later, for representing Donald Trump)—serves as his jumping-off point, but the connection between his core argument and the source material is thin. He writes that “[t]he resurgence of anti-Semitism on the so-called alt-right is not, for now, a genuine political danger.” Later, he goes on:

So far . . . the danger to Jews has remained in the realm of the potential, of fears and doubts rather than immediate threats. When Jewish leftists complain that other parts of the left-coalition do not take anti-Semitism seriously, they are likely to be met with the response that this is because anti-Semitism is not serious.

Kirsch, in the process of his own dismissal of fears about antisemitism as presently unfounded, accuses the left of being the ones not taking antisemitism seriously—without any corroborating evidence whatsoever.

A few paragraphs later, Kirsch examines two incidents to supposedly prove the left’s indifference. First, he cites Trayon White, a DC city councilman who blamed the Rothschilds for controlling the weather. This is, of course, an antisemitic conspiracy theory, and the left treated it as such: White was forced to apologize. The other example involves “supporters of Jeremy Corbyn” blaming Israel for assassinations for which Russia was responsible, though Kirsch does not say how numerous or how powerful these supporters are. Kirsch follows these insufficient examples by writing that “people who put out lists of ‘neoconservatives’ and members of the ‘Israel Lobby’ during the George W. Bush administration are not likely now to have much sympathy for Jewish feelings of vulnerability and persecution.” The quotation marks he coyly deploys do not make the existence of a neoconservative ideological movement or a group of people who lobby on behalf of Israel’s interests any less real, nor do they make the left’s discussion of these entities inherently antisemitic. Kirsch’s broad-brush insinuations are a poor substitute for actual evidence in support of his claims.

That these two Kirsches—the curious, perceptive critic and the incurious, obtuse political writer—exist side-by-side is the confounding reality of Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer?. In the book’s introduction, Kirsch admits that “the essays collected in this book . . . were not written with a program in mind,” but that he believed that they were ultimately all animated by the “intersection of poetry and religion.” This is true of the book’s successful essays and not true, even conceptually, of its bad ones. Perhaps if he had kept this goal in mind when he assembled the collection, Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer? would have been a more cohesive book. Instead, we have a compilation that vacillates wildly in quality and ultimately crumbles under the weight of its contradictions.

Bradley Babendir is an editor-at-large at Chicago Review of Books. His work has been published by NPR, TheWashington Post, The Paris Review, Pacific Standard, and elsewhere.