This Purim, Stand Against Kahanism

We are still living with the consequences of the Hebron massacre.

AS WE MOURN the murder of 50 in a Christchurch mosque, we also remember a massacre that looms large in Israeli and Palestinian memory. On Purim morning, 1994, Baruch Goldstein, an American Jewish settler living in the Kiryat Arba settlement outside Hebron, opened fire on hundreds of Palestinian Muslims praying at the Ibrahimi mosque in the Tomb of the Patriarchs, killing 29 people and injuring upwards of a hundred more. Goldstein, who entered the Tomb wearing an IDF uniform with a military-issued weapon in hand, was a student of Meir Kahane, the racist and ultra-nationalist Orthodox rabbi who remains a foundational figure for the Israeli far right.

This Purim, on the 25th anniversary of the attack, members of All That’s Left: Anti-Occupation Collective have organized Purim Against Kahanism—a commemoration of the Goldstein Massacre, a call against the segregation and sterilization of Hebron that followed, and a protest of the occupation being carried out in our names.

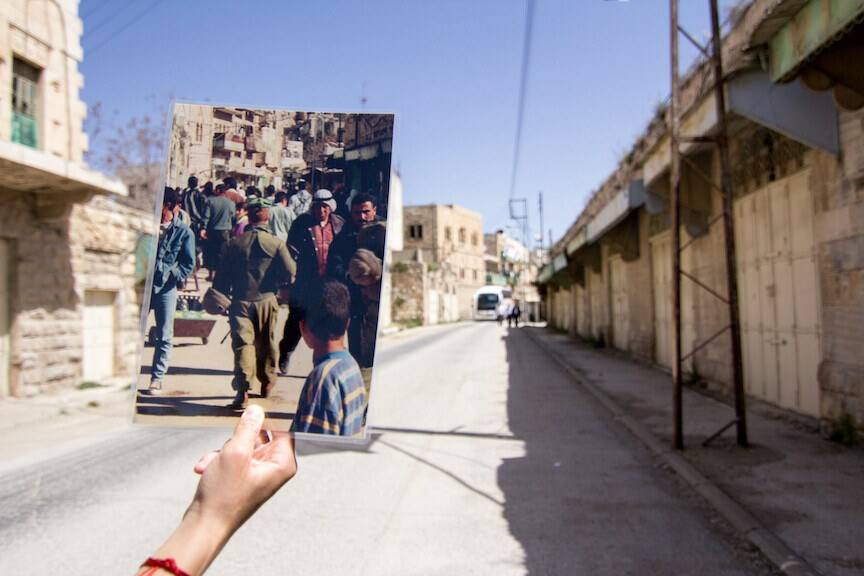

That Purim morning 25 years ago ushered in a new stage of oppression against Palestinians in the city of Hebron. Rather than promoting healing and reconciliation, Israeli authorities instead put Palestinians under curfew for two months following the massacre in order to protect the city’s settlers. When the curfew was lifted, the sterilization (the army’s official term) of the city began: roads were closed to Palestinian traffic and Palestinian markets and shops were shut down.

This policy of sterilization is still in place today, turning the heart of the largest Palestinian city in the West Bank into a ghost town. Goldstein’s grave has become a site of pilgrimage. His tomb, located in the state-funded Meir Kahane Park in Kiryat Arba, proudly announces a man of “clean hands and pure heart,” who “gave his soul for the people of Israel, its Torah, and its land.”

Hebron is extreme, but not unique. Today, the ideology of Kahane is enjoying a resurgence. Emboldened by Donald Trump, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has brokered a deal that has all but ensured that those who proudly espouse Kahane’s beliefs will likely sit in the next Knesset. Even after this week’s Supreme Court decision barring Michael Ben-Ari from running in the upcoming election because of racism and incitement, Kahane enthusiast Itamar Ben-Gvir is still on the Jewish Power Party’s list. Further, following Ben-Ari’s exclusion, supporters are calling for Ben-Gvir to assume greater leadership in the party, and for Baruch Marzel, a settler from Hebron who served as an aide to Kahane and has called for violence against Palestinians as well as for their forced transfer, to become a minister in the next government.

Denouncing Kahanism cannot end with Kahane or with Goldstein. We must also condemn the sterilization in Hebron that stemmed from Goldstein’s actions and the occupation that his followers, as well as both the US and Israeli governments and many Jewish communal institutions around the world, continue to support. We must recognize how the entrance of ultra-conservative discourse into the Knesset reflects mainstream ethnic discrimination in Israel/Palestine. It is incumbent upon Jewish communities around the world to join movements engaging in principled action against the displacement of Palestinians and toward a future of equality and dignity for all residents of the land.

Violence in Hebron on Purim is not only a matter of historical memory. Purim has remained a day of violence in the city, as settlers continue to engage in belligerent parades extolling the legacy of Jewish supremacy in the city. Purim is a complicated holiday, and the Book of Esther is a complicated text—dark, confusing, and violent—ending with a reverse genocide carried out by Jews, a fact which extremist factions in the Jewish community still draw inspiration from today. This dark potential was recognized by the rabbis of the Talmud, who debated whether to include the Book of Esther in the biblical canon for fear of how its violence would be understood.

But perhaps this also means that The Book of Esther is a rich text with which to confront the current crisis. The text is inherently political, raising serious questions about power, violence, and the treatment of minorities. It offers no easy answers, and yet the Purim ethos of v’nahafoch hu—of reversal and the topsy-turvy break from routine—reminds us that a revolution is never as far as it may seem.

Towards the end of Megillat Esther, we are told that Mordechai and Esther “sent out letters to all of the Jews” (Esther 9:30). Their final act is to disseminate their message, to reach out to the Jewish communities of all 127 provinces ruled by Achashverosh with “words of peace and truth.” All That’s Left’s Purim Against Kahanism has been organized in this spirit. There are already events planned in Jerusalem, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and we invite you to plan your own event: to gather a group of friends and light yahrtzeit candles in memory of Goldstein’s victims. We encourage you to use our Purim Against Kahanism text, and to add your own readings, songs, and discussion questions.

The darkness of the Goldstein Massacre is resonant with the darkness of the Purim tale. The Book of Esther is in fact the only book in the Hebrew Bible in which the name of God does not appear. And yet it is precisely from this place of absence and despair that redemption is revealed in the Purim story. The Hasidic book of commentary Netivot Shalom refers to the salvation of Purim as “an awakening from below,” rather than one from the heavens above. Mordechai and Esther reverse an unjust decree through their own protest and action. Surely the same can be true for us today.

Let us rise up in the spirit of Esther, to plead on behalf of our friends, our allies, and our communities, “Oh how can I bear to see the evil that has come upon my people? How can I bear to see the destruction of my kindred?” (Esther 8:6). And let us, in the spirit of the great queen, be moved to action, “because who knows whether it is only for this moment that I have arrived in the kingdom?” (Esther 4:14).

Maya Rosen is the Israel/Palestine fellow at Jewish Currents.